Hejaz railway

Template:Short description Template:Use dmy dates Template:Use Indian English Template:Infobox rail Template:Hejaz railway

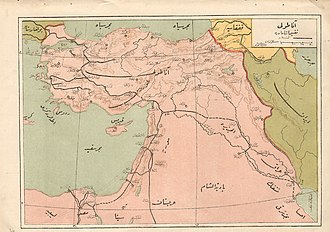

The Hejaz railway (also spelled Hedjaz or Hijaz; Template:Langx Template:Transliteration or Template:Langx, Template:Langx, Template:Langx) was a narrow-gauge railway (Template:RailGauge track gauge) that ran from Damascus to Medina, through the Hejaz region of modern-day Saudi Arabia, with a branch line to Haifa on the Mediterranean Sea. The project was ordered by Sultan Abdul Hamid II in March 1900.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

It was a part of the Ottoman railway network and the original goal was to extend the line from the Haydarpaşa Terminal in Kadıköy, Istanbul beyond Damascus to the Islamic holy city of Mecca. However, construction was interrupted due to the outbreak of World War I, and it reached only to Medina, Template:Convert short of Mecca. The completed Damascus to Medina section was Template:Convert. It was the only railway completely built and operated by the Ottoman Empire.

The main purpose of the railway was to establish a connection between Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire and the seat of the Islamic Caliphate, and Hejaz in Arabia, the site of the holiest shrines of Islam and Mecca, the destination of the Hajj annual pilgrimage. Other objectives were to improve the economic and political integration of the distant Arabian provinces into the Ottoman state, and to facilitate the transportation of military forces.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

In the Jordanian and Saudi deserts, treasure hunters searching for golden hoards allegedly hidden by the retreating Turks during the Arab Revolt under or around the railway tracks have led to massive and ongoing destruction of abandoned tracks and stations, as well as of still maintained sections.<ref name= esq>Template:Cite magazine</ref><ref name= noe>Template:Cite magazine</ref> Rails are pilfered for scrap.<ref name= esq/><ref name= noe/> The Syrian Civil War has led to further damage to railway structures in Syria.<ref name= esq/><ref name= noe/>

History

Prior to the construction of the line, it took 40 days from Damascus to Medina.<ref name=":2">Template:Cite web</ref> The railway shortened the time to 5 days.<ref name=":2" /> The railway is the only railway which was operated and built by the Ottoman Empire.<ref name=":4">Özyüksel (2014), p. 18.</ref> At first, German engineers were employed as technical support, however over time they were replaced by Ottoman technicians.<ref name=":4" /> According to Özyüksel, the Ottomans built the project in order to weaken the Arab nationalist movements and strengthen the empire's Islamist positioning.<ref>Özyüksel (2014), p. 19.</ref>

The loss of Christian territories in Europe turned the Ottoman Empire into a more Islamic centred entity according to Özyüksel . The empire under Sultan Abdulhamid was concerned with non-Turks in the empire turning to nationalism and thus disintegrating the empire. The Ottomans sought to use Islam to unite their various subjects and prevent the spread of nationalist ideas. The railway was meant to enhance the image of the Sultan as a paramount figure in the Islamic world.<ref name=":6" /> The construction of the Hejaz railway would assist the Ottoman empire in preventing Bedouin attacks on pilgrims to Mecca and Medina. Template:Clarify it was meant to weaken the independence of amirs in Mecca and Medina and strengthen the Ottoman state in the region.<ref name=":6" />

Construction

Project; survey

Railways were experiencing a building boom in the late 1860s, and the Hejaz region was one of the many areas up for speculation. The first such proposal involved a railway stretching from Damascus to the Red Sea. This plan was soon dashed however, as the Amir of Mecca raised objections regarding the sustainability of his own camel transportation project should the line be constructed.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Ottoman involvement in the creation of a railway began with Colonel Ahmed Reshid Pasha, who, after surveying the region on an expedition to Yemen in 1871–1873, concluded that the only feasible means of transport for Ottoman soldiers traveling there was by rail. Other Ottoman officers, such as Osman Nuri Pasha, also offered up proposals for a railway in the Hejaz, arguing its necessity if security in the Arabian region were to be maintained.<ref name="auto">Template:Cite book</ref>

Funding and symbolism

Many around the world did not believe that the Ottoman Empire would be able to fund such a project: it was estimated the railway would cost around 4 million Turkish lira, a sizeable portion of the budget. The Ziraat Bankasi, a state bank which served agricultural interests in the Ottoman Empire, provided an initial loan of 100,000 lira in 1900. This initial loan allowed the project to commence later the same year. Abdul Hamid II called on all Muslims in the world to make donations to the construction of the Hejaz Railway.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The project had taken on a new significance. Not only was the railway to be considered an important military feature for the region, it was also a religious symbol. Hajis, pilgrims on their way to the holy city of Mecca, often didn't reach their destination when travelling along the Hejaz route. Unable to contend with the tough, mountainous conditions, up to 20% of hajis died on the way.<ref name="auto"/>

Abdul Hamid was adamant that the railway stand as a symbol for Muslim power and solidarity: this rail line would make the religious pilgrimage easier not only for Ottomans, but all Muslims. As a result, no foreign investment in the project was to be accepted. The Donation Commission was established to organize the funds effectively, and medallions were given out to donors. Despite propaganda efforts such as railway greeting cards, only about 1 in 10 donations came from Muslims outside of the Ottoman Empire. One of these donors, however, was Muhammad Inshaullah, a wealthy Punjabi newspaper editor. He helped to establish the Hejaz Railway Central Committee.<ref name="auto"/> The BBC said the project was funded completely by donations.<ref name=":2" />

The attempt to reach the Hejaz via rail despite major economic incentives outside the Hajj season is probably due to religious and political reasons according to Özyüksel.<ref>Özyüksel (2014), p. 212.</ref>

Resources; construction work

Access to resources was a significant stumbling block during construction of the Hejaz Railway. Water, fuel, and labor were particularly difficult to find in the more remote reaches of the Hejaz. In the uninhabited areas, camel transportation was employed not only for water, but also food and building materials. Fuel, mostly in the form of coal, was brought in from surrounding countries and stored in Haifa and Damascus.

Labor was certainly the largest obstacle in the construction of the railway. In the more populated areas, much of the labor was fulfilled by local settlers as well as Muslims in the area, who were legally obliged to lend their hands to the construction. This labor was largely employed in the treacherous excavation efforts involved in railway construction. In the more remote areas the railway would be reaching, a more novel solution was put to use. Much of this work was completed by railway troops of soldiers, who in exchange for their railway work, were exempt from one third of their military service.<ref name="auto"/>

As the rail line traversed treacherous terrain, many bridges and overpasses had to be built. Since access to concrete was limited, many of these overpasses were made of carved stone and stand to this day.

Engineers

Both Ottoman and foreign engineers worked together on the construction of the Hejaz Railway, and it was the first Ottoman railway on which Muslim engineers who had graduated from Ottoman engineering schools worked in significant numbers.<ref>Template:Citation</ref> The construction of the Hejaz railway progressed slower than expected, primarily due to the inexperience of Ottoman engineers. The Hendese-i Mülkiye, the empire’s first engineering school, had been founded only 16 years earlier, limiting the availability of skilled local engineers. As a result, the Ottoman administration abandoned its initial policy of hiring only locals and brought in foreign experts. Engineers from the Anatolian and Baghdad railways were transferred, and under the leadership of the experienced German engineer Meissner, construction accelerated.<ref name=":8">Özyüksel (2014), p. 218.</ref>

Despite this, Sultan Abdülhamid II remained committed to employing Muslim engineers. In 1904, 17 Muslim engineers were hired, and to further develop local expertise, the Ottomans sent engineers to Germany for training. Over time, Muslim Ottoman engineers became involved at all levels of the project. In particular, the section south of al-Ula was staffed exclusively by Muslims, as Christians were barred from entering. The final stretch from al-Ula to Medina was completed successfully under the leadership of Haji Muhtar Beg, relying entirely on Muslim engineers and workers.<ref name=":8" />

Transportation volume

The Haifa - Dera - Damascus branch of the Hejaz railway was about a fifth of the total rail built for the Hejaz railway and accounted for three quarters of traffic.<ref name=":5">Özyüksel (2014), p. 212.</ref>

Economic influence

The Hejaz district did not enjoy significant positive economic effects from the Hejaz railway according to Özyüksel. Haifa, a port at the end of a branch line of the Hejaz railway is said to have enjoyed significant growth partily due to the railway connection.<ref name=":5" />

Arab opposition

The Emir Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca viewed the railway as a threat to Arab suzerainty, since it provided the Ottomans with easy access to their garrisons in Hejaz, Asir, and Yemen. From its outset, the railway was the target of attacks by local Arab tribes. These were never particularly successful, but neither were the Turks able to control areas more than a mile or so either side of the line. Due to the locals' habit of pulling up wooden sleepers to fuel their camp-fires, some sections of the track were laid on iron sleepers.

In September 1907, as crowds celebrated the rail reaching Al-'Ula station, a rebellion organized by the tribe of Harb threatened to halt progress. The rebels objected to the railway stretching all the way to Mecca; they feared they would lose their livelihood as camel transport was made obsolete.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> It was later decided by Abdul Hamid that the railway would only go so far as Medina.<ref name="auto" />

British opposition

Due to a British ultimatum, Özyüksel says the Ottomans were not able to build the Aqaba exit from the Hejaz network.<ref name=":3" /> The British backed the publishing of newspaper articles in India against the Hejaz railway in order to prevent Indian muslims from donating to the Hejaz railway.<ref name=":7">Özyüksel (2014), p. 217.</ref> The British also banned the wearing of Hejaz railway medals which were gifted to those who had donated to the construction of the railway. The British claimed that the donations went to the Sultan's own devices and not for the railway itself.<ref name=":7" /> British use of the railway included regular trips by Gertrude Bell, who visited Al-Jizah often.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

French opposition

The French opposed the Afula - Jerusalem track, which prevented the Ottomans from completing that segment of the Hejaz Network.<ref name=":3">Özyüksel (2014), p. 20.</ref>

Completion (1908-13)

Under the supervision of chief engineer Mouktar Bey, the railway reached Medina on 1 September 1908, the anniversary of the Sultan's accession.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> However, many compromises had to be made in order to finish by this date, with some sections of track being laid on temporary embankments across wadis. In 1913 the Hejaz Railway Station was opened in central Damascus as the starting point of the line.

Reception

The railways were received "enthusiastically" according to Özyüksel. The press in countries with significant Muslim populations outside the Ottoman empire including Egypt and India covered the project and also asked Muslims to assist the Ottoman Caliph in the building of the railway.<ref name=":6">Özyüksel (2014), p. 216.</ref>

World War I

To fuel locomotives operating on the railway during World War I, the German Army produced shale oil from the Yarmouk oil shale deposit.<ref name=alali>Template:Cite conference</ref><ref name=Jordan>Template:Cite reportTemplate:Dead link</ref> The Turks constructed a military railway from the Hejaz line to Beersheba, opening on 30 October 1915.<ref name="cotterell-ch3">Template:Cite book</ref>

The Hejaz line was repeatedly attacked and damaged, particularly during the Arab Revolt, when Ottoman trains were ambushed by the guerrilla force led by T. E. Lawrence.

- On 26 March 1917, T. E. Lawrence (known as Lawrence of Arabia) led an attack on the Aba el Naam Station, taking 30 prisoners and inflicting 70 casualties on the garrison. He went on to say, "Traffic was held up for three days of repair and investigation. So we did not wholly fail."<ref name="TE">Template:Cite book</ref>

- In May 1917, British bombers dropped bombs on Al-'Ula Station. In July 1917, Stewart Newcombe, a British engineer and associate of Lawrence, conspired with forces from the Egyptian and Indian armies to sabotage the railway. The Al-Akhdhar station was attacked and 20 Turkish soldiers were captured.<ref name=":0">Template:Cite book</ref>

- In October 1917, the Ottoman stronghold of Tabuk fell to Arab rebels. The Abu-Anna’em station was also captured.

- In November 1917, Sharif Abdullah and the tribe of Harb attacked Al-Bwair station and destroyed two locomotives.

- In December 1917, a group of men led by Ibn Ghusiab derailed a train on the line south of Tabuk.<ref name=":1">Template:Cite web</ref>

With the Arab Revolt and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, it was unclear to whom the railway should belong. The area was divided between the British and the French, both eager to assume control. However, following years of neglected maintenance, many sections of track fell into disrepair; the railway was effectively abandoned by 1920. In 1924, when Ibn Saud took control of the peninsula, plans to revive the railway were no longer on the agenda.

World War II

In the Second World War, the Samakh Line (from Haifa to Deraa at the Syrian border and to Damascus) was operated for the Allied forces by the New Zealand Railway Group 17th ROC, from Afula (with workshops at Deraa and Haifa). The locomotives were 1914 Borsig and 1917 Hartmann models from Germany. The line, which had been operated by the Vichy French,Template:Dubious was in disrepair. Trains over the steep section between Samakh (now Ma'agan) and Deraa were 230 tons maximum, with 1,000 tons moved in 24 hours. The group also ran 60 miles (95 km) of branch line, including Afula to Tulkarm.<ref>Judd, Brendon The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War (2003, 2004 Auckland, Penguin) Template:ISBN</ref>

1960s

The railway south of the modern Jordanian–Saudi Arabian border remained closed after 1920 and the fall of the Ottoman Empire. An attempt was made to rebuild it in the mid-1960s, but then abandoned due to the Six-Day War in 1967.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Successor lines

Two connected sections of the main line are in service:

- from Amman in Jordan to Damascus in Syria, as the Hedjaz Jordan Railway,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and

- from phosphate mines near Ma'an to the Gulf of Aqaba, as the Chemin de Fer de Hedjaz Syrie,Template:Dubious or the Aqaba Railway Corporation.Template:Citation needed

Israel Railways partially rebuilt the long-defunct Haifa extension, the Jezreel Valley railway, using standard gauge, with the possibility of someday extending it to Irbid in Jordan. The rebuilt line opened from Haifa to Beit She'an in October 2016.<ref name=MaarO16>Template:Cite news</ref>

Saudi Arabia completed the construction of the Medina-Mecca line (via Jeddah) with the Haramain high-speed railway in 2018.Template:Citation needed

Azmi Nalshik the head of Jordan Hejaz Railways said that the railways is considered a waqf, meaning it belongs to all Muslims and therefore cannot be sold.<ref name=":2" />

Plans for the future

On 4 February 2009 the Turkish Transport Minister Binali Yıldırım said in Riyadh that Turkey planned to rebuild its section, and called on Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Syria to come together and complete the restoration.<ref>"Kingdom, Turkey decide to restore historic Hejaz railway". Ghazanfar Ali Khan for Arab News, Jeddah, 5 February 2009. Re-accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

Also in 2009, Jordan's transport ministry proposed a 990-mile (1590-km) US$5 billion rail network, construction of which could begin in the first quarter of 2012. The planned network would provide freight rail links from Jordan to Syria, Saudi Arabia and Iraq. Passenger rail connections could be extended to Lebanon, Turkey and beyond. The government, which will fund part of the project, is inviting tenders from private firms to raise the rest of the project cost.Template:Citation needed

In November 2018, Middle East Monitor revealed Saudi-Israel's joint plans to revive the railway from Haifa to Riyadh.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> The Turkish minister of transport, Abdulkadir Uraloğlu, announced in December 2024 that Turkey intends to help restore the railway in partnership with the new Syrian government.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Preservation and tourist trains

Railway mechanics have restored many of the original steam-powered locomotives: there are nine in working order in Syria and seven in Jordan.Template:When

Since the accession of Abdullah II in 1999, relations between Jordan and Syria have improved, causing a revival of interest in the railway. The train runs from Qadam station in the outskirts of Damascus, not from the Hejaz Station, which closed in 2004 due to a major commercial development project.Template:Citation needed Trains run from Khadam station on demand (usually from German, British or Swiss groups). The northern part of the Zabadani track is no longer accessible.

Museums and sightseeing

In 2008, the "museum of the rolling stock of Al-Hejaz railway" opened in Damascus' KhadamTemplate:Clarify station after major renovations for an exhibition of the locomotives.Template:Citation needed

An exhibit on the railway's cultural heritage opened in 2019 at Darat al-Funun in Amman.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

As of 2006, there is a small railway museum at the station in Mada'in Saleh in Saudi Arabia<ref>"Move Under Way to Restore Madain Saleh Railway Station", Javid Hassan & P.K. Abdul Ghafour for the Arab News, 22 June 2006. Re-accessed 27 March 2024.</ref> and a larger project in the "Hejaz Railway Museum" in Medina, which opened in 2006.<ref>Article Hejaz Railway Museum Opened Template:Webarchive in the Arab News , 21 January 2006</ref> The museum, which is dedicated to the history and archeology of Medina is 90,000 square meters.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The Medina Terminus was restored in 2005 with railway tracks and locomotive shed.Template:Citation needed

Small non-operating sections of the railway track, buildings and rolling stock are still preserved as tourist attractions in Saudi Arabia. The old railway bridge over the Aqeeq Valley at Medina though was demolished in 2005 due to damage from heavy rain the year before.<ref name= AN05>"Madinah Municipality Razes Hijaz Railway Bridge". Yousif Muhammad for the Arab News, 31 August 2005. Re-accessed 27 March 2024. See here Template:Usurped of the damaged bridge and the Medina station before restoration among others.</ref>

Trains destroyed by local Arab, French, and British troops during WWI and the Arab Revolt of 1916–1918 can still be seen where they were attacked.<ref name=SA>James Nicholson. Route Guide: Saudia Arabia at thehejazrailway.com (see station by station). Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

Ongoing destruction

As of 2024, in the Jordanian and Saudi deserts, the legend of Ottoman treasure hidden by retreating Turks during the Arab Revolt under or around the railway tracks persists strongly.<ref name= esq/><ref name= noe/> Locals and adventurers from the wider Middle East have been known to dig around the tracks and stations, hoping to uncover gold hoards.<ref name= esq/><ref name= noe/> Some even claim to possess maps from Turkey indicating potential treasure sites. Holes are pockmarking the ground, station floors, roofs and walls have been smashed in the search, on top of rails being pilfered for scrap.<ref name= esq/><ref name= noe/> In Syria, the civil war did not spare the historic railway's inventory either.<ref name= esq/><ref name= noe/>

Revival

In September 2025, plans to revive the railway from Jordan through Syria to Turkey were revived in an agreement to complete the 30km superstructure<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Stations

Some of the stations were located near the traditional Hajj caravan stations, where the Ottomans had built fortified inns (see Ottoman Hajj route).

The Arabic word for station is "Mahaṭat". The Ottoman- and interwar-period spelling tends to be simpler than the current official ones.

Pre-WWI, the Ottomans used French spelling.<ref name=BLS/>

- Damascus Kanawat/Qanawat,<ref name=BLS>Syria & Lebanon Railways: Passenger Stations & Stops, "6. Damas - Medine", p. 4/5, 11/2000. The Branch Line Society (BLS), Stoke Gifford, UK. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref><ref name=map>James Nicholson. Maps: Syria, Jordan, Saudia Arabia sections at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref> 1906 extension

- Damascus Kadem/Qadem<ref name=BLS/><ref name=map/> (Cadem Works)

- Kiswe<ref name=map/> (Al-Kiswah)

- Dair Ali<ref name=map/> (Deir Ali)

- Mismia<ref name=map/>/ Al-Mismiya,<ref name=BLS/> also Masjid/Masjed

- Jabab/Jebab<ref name=BLS/><ref name=map/> (Ghabaghib)

- Habab (1912)<ref name=BLS/>/Khebab<ref name=map/> (Khabab); in 2000, the station is listed, also at km 69.1, as/at As-Sanamain<ref name=BLS/>

- Mehaye<ref name=map/>/Mohadje<ref name=BLS/> (Mahajjah/Muhajjah)

- Shakra<ref name=map/> (Shaqra(h))

- Ezra<ref name=map/> (Ezraa/Esra/Izra)

- Gazali<ref name=BLS/> (Al-Ghazali, Khirbet Ghazaleh)

- Haifa-Daraa branch line (Jezreel Valley railway)

- Deraa<ref name=map/> (Daraa)

- Kum Gharz/Koumgarze;<ref name=BLS/> now Kawm Gharz (see "Mahattat Kawm Gharz" at MapCarta, Template:Coord).

- Branch line to Bosra

- Nessib<ref name=map/> (Nasib)

- Syria-Jordan border

- Jaber<ref name=BLS/> (Jabir as-Sirhan; see Jaber Border Crossing)

- Mafrak<ref name=BLS/> (Mafraq).<ref name=map/> Has a Hajj fort, Khan or Qal'at el-Mafraq.<ref name=Shqour>Template:Cite book</ref>

- Samra/<ref name=map/> Semra/Sumra<ref name=BLS/> (Khirbet as-Samra, Template:Coord)

- Zerqa<ref name=map/>/Zarqa.<ref name=BLS/> Has a Hajj fort, Manzil az-Zarqa or Qasr Shabib.<ref name= Shqour/>

- Rusaifa (in 1930, 38)<ref name=BLS/>

- Amman<ref name=map/>

- Kassir<ref name=map/> (Qasr; see Al-Qasr, Karak)

- Libban<ref name=map/>/Lubin<ref name=BLS/> (Al Lubban)

- Jiza<ref name=map/>/Zizia<ref name=BLS/> (Djizeh/Al-Jizah). Has a Hajj fort, Manzil or Qal'at Zizya<ref name= Shqour/>

- Deba'a<ref name=map/>/Daba'a/Dab'ah<ref name=BLS/>

- Khan Zebib<ref name=map/>/Khan az Zabib<ref name=BLS/> (Khan az-Zabib: station at Template:Coord; Umayyad site see here).

- Sultani<ref name=map/>/Suaka<ref name=BLS/> (Suaq/Suaqa)

- Qatrana<ref name=map/> (Qatraneh) triangle. Has a Hajj fort, Khan Qatrana/<ref name =Shqour/>Qasr al-Qatraneh.

- Menzil<ref name=map/>/Manzil<ref name=BLS/>

- Harbet-ul-Kreika (1912)<ref name=BLS/>/Faraifra<ref name=map/> (Farafra)

- Al Hasa<ref name=map/> (al-Hasa/el-Hassa.)<ref name=BLS/> The station stands 5 km southeast of the Ottoman Hajj fort of Khan al-Hasa (1760, Template:Coord), along Wadi el-Hasa's upper course.<ref>Qal'at Al-Hasa at Jordan's Hajj Ottoman forts. Accessed 1 Apr 2024.</ref>

- Jerouf<ref name=map/> (Jurf ad-Darawish)<ref name=BLS/>

- Aneiza/<ref name=BLS/> Unaiza<ref name=map/> (Uneiza/'Unayzah; in Husseiniyeh, Ma'an, Jordan). Has a Hajj fort, Khan al-'Unayzah/<ref name =Shqour/> Qal'at 'Unaiza.

- Vadi-Djerdoun (1912)<ref name=BLS/>/Jerdun<ref name=map/>

- Mahan (1912)<ref name=BLS/>/Ma'an<ref name=map/> (Old Station). Has a Hajj fort, Manzilt or Qal'at Ma'an.<ref name= Shqour/>

- Ghadir al Hajj<ref name=map/> (Gadir al-Hajj)

- Abu Tarfa/<ref name=BLS/>Abu Tarafa or Ghadr el Hadj,<ref name=BLS/> only post-WWII

- Shidiyya/Shedia,<ref name=BLS/> Bir Shedia<ref name=map/>

- Fassu'a (station only appears on plan here above, in no other source). Has a Hajj fort, Manzilt or Qal'at Fassu'a,<ref name =Shqour/> which stands along the railway line.<ref>Qal'at Fassu'a Template:Webarchive at Jordan’s Ottoman Hajj Forts. Accessed 28 March 2024.</ref>

- Aqaba Shamia, name used by thehejazrailway.com<ref name=map/> - probably same as Aqaba al-Hejaz<ref name=BLS/>

- Hittiyya<ref name=BLS/>

- Batn al Ghul<ref name=map/> (Batn al-Ghul/Batn al-Gul)

- Wadi Rutum/<ref name=BLS/> Wadi Rutm<ref name=map/> (Wadi Rassim/<ref name=BLS/>Wadi Rasem)

- Tel es Sham/Tel Shahem/<ref name=BLS/> Tel Shahm<ref name=map/> (Tel esh-Sham)

- Ramleh/<ref name=BLS/> Ramle<ref name=map/>

- Mudévéré/<ref name=BLS/>Mudawwara.<ref name=map/> Has a Hajj fort, Manzilt or Qal'at al-Mudawwara.<ref name= Shqour/>

- Jordan - Saudi Arabia border

- Halat Ammar<ref name=map/>/Kalaat Amara/Haret Ammar<ref name=BLS/>

- Zat-ul-Hadj (1912)/<ref name=BLS/>Dhat al-Hajj. Has a Hajj fort.<ref name= map/>

- Bir Hermas (1911)/<ref name=BLS/>Bir Ibn Hermas<ref name= map/>

- El-Hazim/Al-Hazm<ref name= map/>

- Muhtatab (Al-Muhtatab)<ref name= map/>/Makhtab<ref name=BLS/>

- Tebouk (1912)/<ref name=BLS/>Tabuk<ref name= map/>

- Wadi Ithil (Wadi al-Athily)<ref name= map/>

- Khashm Birk<ref name= map/>/Sahr ul Ghul<ref name=BLS/>

- Dar al-Hajj<ref name= map/> (Dahr al-Hajj/Qareen al-Ghazal)

- Mustabgha<ref name= map/> (Al-Mustabagha)

- Ashtar alimentation (1911)/Ashdar (1912)/<ref name=BLS/> al-Akhdar<ref name= map/> (Al-Ukhaydir). Has a Hajj fort, Qal'at al-Akhdar/el-Akhthar.

- Maqsadat ad Dunya<ref name=BLS/>

- Khamis<ref name= map/>/Khamees/<ref name=BLS/>Khamisa

- Disa'ad<ref name= map/> - Al-Assda (al-Khanzira)

- Muazzam<ref name= map/>/Muazzem/Al-Mu'azzam

- Khashm Sana'a<ref name= map/> (also Khism, Khashim Sanaa)<ref name=BLS/>

- Al-Muteli' (km 883 according to route plan above, or km 878<ref name=BLS/>)

- Dar al-Hamra<ref name= map/>

- Mutalli<ref name= map/>/Matali (km 904)<ref name=BLS/>

- Abu Taqa<ref name= map/>

- El Muzhim<ref name=BLS/>

- Mabrak al-Naga<ref name= map/>/Mabrakat al-Naka<ref name=BLS/>

- Médain Salih (1912)/<ref name=BLS/> Mada'in Saleh/Meda'in Saleh (Al-Hijr/Hegra)<ref name= map/>

- Wadi Hashish<ref name= map/><ref name=BLS/>

- El Oula (1912)/<ref name=BLS/> Alula<ref name= map/>/Al-'Ula

- Bedaï (2911)/<ref name=BLS/> Bedaya<ref name= map/>

- Mashad<ref name= map/><ref name=BLS/>

- Sahl Matran<ref name= map/>/Sahel Mater<ref name=BLS/>

- Zumurrud<ref name= map/>/Zumrud/Zomorod<ref name=BLS/>

- Bir Jadeed<ref name= map/>/Bir el Djedid/<ref name=BLS/>Bir Jadid

- Towaira<ref name= map/>/Tuweiro<ref name=BLS/>

- Wayban<ref name= map/>

- Mudarraj (Madahni)<ref name= map/>

- Hedié (1912)/<ref name=BLS/> Hedia/Hadiyya (Hadiyyah, Al Madinah)<ref>James Nicholson. Hedia Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

- Jeda'a/Jada'a<ref>James Nicholson. Jeda'a Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

- Ebou Naam (1911)/<ref name=BLS/> Abu Na'am/Abu al-Na'am<ref>James Nicholson. Abu Na'am Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

- Istabl Antar<ref>James Nicholson. Istabl Antar Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>/Stabl Antar

- Buveiré (1911)/Buéiré (1912)/<ref name=BLS/> Buwair<ref>James Nicholson. Buwair Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

- Bir Nassif<ref>James Nicholson. Bir Nassif Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

- Buwat<ref>James Nicholson. Buwat Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

- Hafiré (1912)/<ref name=BLS/>Hafira/al-Hafirah<ref>James Nicholson. Hafira Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref> Is on Hajj route.

- Bir Abu Jabir<ref name=BLS/>

- Makhit<ref name=BLS/>/Muhit<ref>James Nicholson. Muhit Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

- Biri Osman<ref name=BLS/>/Bir Osman

- Medine (1912)/<ref name=BLS/>Medina<ref>James Nicholson. Medina Station at thehejazrailway.com. Accessed 27 March 2024.</ref>

- Medina Citadel

Image gallery

-

A coin commemorating the opening of the Ma'an Station of the Hejaz railway

-

Repairing the railway near Ma'an 1918

-

Old railway track to the north of Wadi Rum

-

Inside a wagon of the Hejaz train

-

Steam excursion train at Kanawat station, Damascus, Syria, in 2000

See also

- Arab Mashreq International Railway, planned network in the eastern part of the Arab world

- Haramain high-speed railway (built 2009–2018) between Mecca and Medina

- Baghdad Railway (built 1903–1940), initially a German-Ottoman project

- Similar gauges

- Transport in Jordan

- Ottoman Palestine railways

- Eastern Railway, Ottoman WWI line, Tulkarm to Hadera and Tulkarm to Lydda; connected to Jezreel Valley, Jaffa–Jerusalem, and Beersheba lines

- Jaffa–Jerusalem railway (inaugurated 1892)

- Railway to Beersheba or the 'Egyptian Branch', Ottoman WWI line headed towards the Suez Canal; two lines: (Lidda–) Wadi Surar–Beit Hanoun, and Wadi Surar–Beersheba

- Mandate Palestine & Israel railways

- Palestine Railways, government-owned company and rail monopolist in Mandate Palestine (1920–1948)

- Rail transport in Israel

- Coastal railway line, Israel, main line in Mandate Palestine and Israel

- Israel Railways, the state-owned principal railway company in Israel

References

Further reading

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Judd, Brendon The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War (2003, 2004 Auckland, Penguin) Template:ISBN

- Template:Cite book.

- Template:Cite book

External links

- The Hejaz Railway

- Four podcasts about the Hejaz railway from BBC World service

- pictures and report of travelogue in the Saudi Section of Hejaz railway

- BBC: "A piece of railway history"

- BBC: "Pilgrim railway back on track"

- http://www.hejaz-railroad.info/Galerie.html

- Many pictures from the Hidjaz Railway stations from a 2008 trip across Syria

- Extensive website on the Hejaz railway Template:Webarchive

- Yarmuk River railway bridges, 1933 aerial photographs. Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East / National Archives, London.

- Hejaz railway overlay on Google Maps

Template:Rail transport in Saudi Arabia Template:Navbox track gauge Template:Authority control