Kawasaki disease

Template:Short description Template:Use dmy dates Template:Infobox medical condition

Kawasaki disease (also known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome) is a syndrome of unknown cause that results in a fever and mainly affects children under 5 years of age.<ref name=McC2017>Template:Cite journalTemplate:Cite journal</ref> It is a form of vasculitis, in which medium-sized blood vessels become inflamed throughout the body.<ref name=NIH21014/> The fever typically lasts for more than five days and is not affected by usual medications.<ref name=NIH21014/> Other common symptoms include large lymph nodes in the neck, a rash in the genital area, lips, palms, or soles of the feet, and red eyes.<ref name=NIH21014/> Within three weeks of the onset, the skin from the hands and feet may peel, after which recovery typically occurs.<ref name=NIH21014/> The disease is the leading cause of acquired heart disease in children in developed countries, which include the formation of coronary artery aneurysms and myocarditis.<ref name=NIH21014/><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

While the specific cause is unknown, it is thought to result from an excessive immune response to particular infections in children who are genetically predisposed to those infections.<ref name=McC2017/> It is not an infectious disease, that is, it does not spread between people.<ref name=StatPearls/> Diagnosis is usually based on a person's signs and symptoms.<ref name=NIH21014/> Other tests such as an ultrasound of the heart and blood tests may support the diagnosis.<ref name=NIH21014/> Diagnosis must take into account many other conditions that may present similar features, including scarlet fever and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.<ref name=SHARE2019/> Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, a "Kawasaki-like" disease associated with COVID-19,<ref name=Galeotti2020>Template:Cite journal</ref> appears to have distinct features.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name=Abrams2020>Template:Cite journal</ref>Another disease that can originally be presented with the same symptoms is measles. This is due to similar symptoms such as red eyes, persistent fever, and swollen hands/feet. However, Kawasaki disease is not spread the way measles can be spread from person to person.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Typically, initial treatment of Kawasaki disease consists of high doses of aspirin and immunoglobulin.<ref name=NIH21014/> Usually, with treatment, fever resolves within 24 hours and full recovery occurs.<ref name=NIH21014/> If the coronary arteries are involved, ongoing treatment or surgery may occasionally be required.<ref name=NIH21014/> Without treatment, coronary artery aneurysms occur in up to 25% and about 1% die.<ref name=Kim2006>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name=Mer2014/> With treatment, the risk of death is reduced to 0.17%.<ref name=Mer2014>Template:Cite web</ref> People who have had coronary artery aneurysms after Kawasaki disease require lifelong cardiological monitoring by specialized teams.<ref name=Brogan2020>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Kawasaki disease is rare.<ref name=NIH21014/> It affects between 8 and 67 per 100,000 people under the age of five except in Japan, where it affects 124 per 100,000.<ref name=La2015>Template:Cite book</ref> Boys are more commonly affected than girls.<ref name=NIH21014>Template:Cite web</ref> The disorder is named after Japanese pediatrician Tomisaku Kawasaki, who first described it in 1967.<ref name=La2015/><ref name=pmid6062087>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Signs and symptoms

Kawasaki disease often begins with a high and persistent fever that is not very responsive to normal treatment with paracetamol (acetaminophen) or ibuprofen.<ref name="pmid9665974">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid7760506">Template:Cite journal</ref> This is the most prominent symptom of Kawasaki disease, and is a characteristic sign that the disease is in its acute phase; the fever normally presents as a high (above 39–40 °C) and remittent, and is followed by extreme irritability.<ref name="pmid7760506"/><ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Recently, it is reported to be present in patients with atypical or incomplete Kawasaki disease;<ref name="pmid7841704">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid3819942">Template:Cite journal</ref> nevertheless, it is not present in 100% of cases.<ref name="pmid21881982">Template:Cite journal</ref>

The first day of fever is considered the first day of the illness,<ref name="pmid9665974"/> and its duration is typically one to two weeks; in the absence of treatment, it may extend for three to four weeks.<ref name=Kim2006/> Prolonged fever is associated with a higher incidence of cardiac involvement.<ref name="pmid10931408">Template:Cite journal</ref> It responds partially to antipyretic drugs and does not cease with the introduction of antibiotics.<ref name=Kim2006 /> However, when appropriate therapy is started – intravenous immunoglobulin and aspirin – the fever subsides after two days.<ref name="pmid1709446">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Bilateral conjunctival inflammation has been reported to be the most common symptom after fever.<ref name="pmid21860641">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid14519302">Template:Cite journal</ref> It typically involves the bulbar conjunctivae, is not accompanied by suppuration, and is not painful.<ref name="pmid18401983">Template:Cite journal</ref> This usually begins shortly after the onset of fever during the acute stage of the disease.<ref name="pmid9665974" /> Anterior uveitis may be present under slit-lamp examination.<ref name="pmid4039819">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid10653425">Template:Cite journal</ref> Iritis can occur, too.<ref name="pmid2468129">Template:Cite journal</ref> Keratic precipitates are another eye manifestation (detectable by a slit lamp, but are usually too small to be seen by the unaided eye).<ref name="pmid9665974"/><ref name="pmid18476929">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Kawasaki disease also presents with a set of mouth symptoms, the most characteristic of which are a red tongue, swollen lips with vertical cracking, and bleeding.<ref name="pmid18059239">Template:Cite journal</ref> The mucosa of the mouth and throat may be bright red, and the tongue may have a typical "strawberry tongue" appearance (marked redness with prominent gustative papillae).<ref name=Kim2006 /><ref name="pmid19851663" /> These mouth symptoms are caused by necrotizing microvasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis.<ref name="pmid18059239"/>

Cervical lymphadenopathy is seen in 50% to 75% of children, whereas the other features are estimated to occur in 90%,<ref name="pmid9665974"/><ref name="pmid21860641" /> but sometimes it can be the dominant presenting symptom.<ref name="pmid18476929"/><ref name="pmid8115224">Template:Cite journal</ref> According to the diagnostic criteria, at least one impaired lymph node ≥ 15 mm in diameter should be involved.<ref name="pmid19851663"/> Affected lymph nodes are painless or minimally painful, nonfluctuant, and nonsuppurative; erythema of the neighboring skin may occur.<ref name="pmid9665974" /> Children with fever and neck adenitis who do not respond to antibiotics should have Kawasaki disease considered as part of the differential diagnoses.<ref name="pmid9665974" />

| Less common manifestations | |

|---|---|

| System | Manifestations |

| GIT | Diarrhea, chest pain, abdominal pain, vomiting, liver dysfunction, pancreatitis, hydrops gallbladder,<ref name="pmid3316594">Template:Cite journal</ref> parotitis,<ref name="pmid21860641" /><ref name="pmid19997548">Template:Cite journal</ref> cholangitis, intussusception, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, ascites, splenic infarction |

| MSS | Polyarthritis and arthralgia |

| CVS | Myocarditis, pericarditis, tachycardia,<ref name="pmid19851663"/> valvular heart disease |

| GU | Urethritis, prostatitis, cystitis, priapism, interstitial nephritis, orchitis, nephrotic syndrome |

| CNS | Lethargy, semicoma,<ref name="pmid21860641" /> aseptic meningitis, and sensorineural deafness |

| RS | Shortness of breath,<ref name="pmid19851663"/> influenza-like illness, pleural effusion, atelectasis |

| Skin | Erythema and induration at BCG vaccination site, Beau's lines, and finger gangrene |

| Source: review,<ref name="pmid19851663"/> table.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> | |

In the acute phase of the disease, changes in the peripheral extremities can include erythema of the palms and soles, which is often striking with sharp demarcation<ref name="pmid9665974" /> and often accompanied by painful, brawny edema of the dorsa of the hands or feet, so affected children frequently refuse to hold objects in their hands or to bear weight on their feet.<ref name=Kim2006 /><ref name="pmid9665974" /> Later, during the convalescent or the subacute phase, desquamation of the fingers and toes usually begins in the periungual region within two to three weeks after the onset of fever and may extend to include the palms and soles.<ref name="pmid19483521">Template:Cite journal</ref> Around 11% of children affected by the disease may continue skin-peeling for many years.<ref name="pmid10999876">Template:Cite journal</ref> One to two months after the onset of fever, deep transverse grooves across the nails may develop (Beau's lines),<ref name="pmid18053534">Template:Cite journal</ref> and occasionally nails are shed.<ref name="pmid18053534" />

The most common skin manifestation is a diffuse macular-papular erythematous rash, which is quite nonspecific.<ref name="pmid10083641">Template:Cite journal</ref> The rash varies over time and is characteristically located on the trunk; it may further spread to involve the face, extremities, and perineum.<ref name=Kim2006 /> Many other forms of cutaneous lesions have been reported; they may include scarlatiniform, papular, urticariform, multiform-like erythema, and purpuric lesions; even micropustules were reported.<ref name="pmid16010565">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid18043462">Template:Cite journal</ref> It can be polymorphic, not itchy, and normally observed up to the fifth day of fever.<ref name="pmid8491037">Template:Cite journal</ref> However, it is never bullous or vesicular.<ref name=Kim2006 />

In the acute stage of Kawasaki disease, systemic inflammatory changes are evident in many organs.<ref name="pmid3766134" /> Joint pain (arthralgia) and swelling, frequently symmetrical, and arthritis can also occur.<ref name="pmid21860641" /> Myocarditis,<ref name="pmid20359606">Template:Cite journal</ref> diarrhea,<ref name="pmid19851663"/> pericarditis, valvulitis, aseptic meningitis, pneumonitis, lymphadenitis, and hepatitis may be present and are manifested by the presence of inflammatory cells in the affected tissues.<ref name="pmid3766134"/> If left untreated, some symptoms will eventually relent, but coronary artery aneurysms will not improve, resulting in a significant risk of death or disability due to myocardial infarction.<ref name="pmid19851663"/> If treated quickly, this risk can be mostly avoided and the course of illness cut short.<ref name="pmid12006960">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Other reported nonspecific symptoms include cough, rhinorrhea, sputum, vomiting, headache, and seizure.<ref name="pmid21860641" />

The course of the disease can be divided into three clinical phases.<ref name=Marchesi2018/>

- The acute febrile phase, which usually lasts for one to two weeks, is characterized by fever, conjunctival injection, erythema of the oral mucosa, erythema and swelling of the hands and feet, rash, cervical adenopathy, aseptic meningitis, diarrhea, and hepatic dysfunction.<ref name="pmid19851663" /> Myocarditis is common during this time, and a pericardial effusion may be present.<ref name="pmid9665974" /> Coronary arteritis may be present, but aneurysms are generally not yet visible by echocardiography.

- The subacute phase begins when fever, rash, and lymphadenopathy resolve at about one to two weeks after the onset of fever, but irritability, anorexia, and conjunctival injection persist. Desquamation of the fingers and toes and thrombocytosis are seen during this stage, which generally lasts until about four weeks after the onset of fever. Coronary artery aneurysms usually develop during this time, and the risk for sudden death is highest.<ref name="pmid9665974" /><ref name="pmid7264399">Template:Cite journal</ref>

- The convalescent stage begins when all clinical signs of illness have disappeared, and continues until the sedimentation rate returns to normal, usually at six to eight weeks after the onset of illness.<ref name="pmid19851663" />

Adult onset of Kawasaki disease is rare.<ref name="pmid17443379"/> The presentation differs between adults and children: in particular, it seems that adults more often have cervical lymphadenopathy, hepatitis, and arthralgia.<ref name="pmid19851663"/><ref name="pmid17443379">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Some children, especially young infants,<ref name="pmid3772656">Template:Cite journal</ref> have atypical presentations without the classic set of symptoms.<ref name=Marchesi2018/> Such presentations are associated with a higher risk of cardiac artery aneurysms.<ref name="pmid9665974" /><ref name="pmid1505575">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Cardiac

Heart complications are the most important aspect of Kawasaki disease, which is the leading cause of heart disease acquired in childhood in the United States and Japan.<ref name="pmid19851663"/> In developed nations, it appears to have replaced acute rheumatic fever as the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children.<ref name="pmid9665974"/> Coronary artery aneurysms occur as a sequela of the vasculitis in 20–25% of untreated children.<ref name="pmid3774580">Template:Cite journal</ref> It is first detected at a mean of 10 days of illness and the peak frequency of coronary artery dilation or aneurysms occurs within four weeks of onset.<ref name="pmid7264399"/> Aneurysms are classified into small (internal diameter of vessel wall <5 mm), medium (diameter ranging from 5–8 mm), and giant (diameter > 8 mm).<ref name="pmid19851663" /> Saccular and fusiform aneurysms usually develop between 18 and 25 days after the onset of illness.<ref name="pmid9665974" />

Even when treated with high-dose IVIG regimens within the first 10 days of illness, 5% of children with Kawasaki disease develop at the least transient coronary artery dilation and 1% develop giant aneurysms.<ref name="pmid7491221">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid9427895">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid8313588">Template:Cite journal</ref> Death can occur either due to myocardial infarction secondary to blood clot formation in a coronary artery aneurysm or to rupture of a large coronary artery aneurysm. Death is most common two to 12 weeks after the onset of illness.<ref name="pmid9665974" />

Many risk factors predicting coronary artery aneurysms have been identified,<ref name="pmid10931408"/> including persistent fever after IVIG therapy,<ref name="pmid18260333">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid1801561">Template:Cite journal</ref> low hemoglobin concentrations, low albumin concentrations, high white-blood-cell count, high band count, high CRP concentrations, male sex, and age less than one year.<ref name="pmid3950818">Template:Cite journal</ref> Coronary artery lesions resulting from Kawasaki disease change dynamically with time.<ref name=Kim2006/> Resolution one to two years after the onset of the disease has been observed in half of vessels with coronary aneurysms.<ref name="pmid8822996">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid3802442">Template:Cite journal</ref> Narrowing of the coronary artery, which occurs as a result of the healing process of the vessel wall, often leads to significant obstruction of the blood vessel and the heart not receiving enough blood and oxygen.<ref name="pmid8822996" /> This can eventually lead to heart muscle tissue death, i.e., myocardial infarction (MI).<ref name="pmid8822996" />

MI caused by thrombotic occlusion in an aneurysmal, stenotic, or both aneurysmal and stenotic coronary artery is the main cause of death from Kawasaki disease.<ref name="pmid3712157">Template:Cite journal</ref> The highest risk of MI occurs in the first year after the onset of the disease.<ref name="pmid3712157" /> MI in children presents with different symptoms from those in adults. The main symptoms were shock, unrest, vomiting, and abdominal pain; chest pain was most common in older children.<ref name="pmid3712157" /> Most of these children had the attack occurring during sleep or at rest, and around one-third of attacks were asymptomatic.<ref name="pmid9665974" />

Valvular insufficiencies, particularly of mitral or tricuspid valves, are often observed in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease due to inflammation of the heart valve or inflammation of the heart muscle-induced myocardial dysfunction, regardless of coronary involvement.<ref name="pmid8822996"/> These lesions mostly disappear with the resolution of acute illness,<ref name="pmid3341217">Template:Cite journal</ref> but a very small group of the lesions persist and progress.<ref name="pmid2382613">Template:Cite journal</ref> There is also late-onset aortic or mitral insufficiency caused by thickening or deformation of fibrosed valves, with the timing ranging from several months to years after the onset of Kawasaki disease.<ref name="pmid3958349">Template:Cite journal</ref> Some of these lesions require valve replacement.<ref name="pmid8665019">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Other

Other Kawasaki disease complications have been described, such as aneurysm of other arteries: aortic aneurysm,<ref name="pmid11274955">Template:Cite journal</ref> with a higher number of reported cases involving the abdominal aorta,<ref name="pmid8741316">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid7572158">Template:Cite journal</ref> axillary artery aneurysm,<ref name="pmid21691693">Template:Cite journal</ref> brachiocephalic artery aneurysm,<ref name="pmid18704549">Template:Cite journal</ref> aneurysm of iliac and femoral arteries, and renal artery aneurysm.<ref name=Kim2006 /><ref name="pmid8901658">Template:Cite journal</ref> Other vascular complications can occur such as increased wall thickness and decreased distensibility of carotid arteries,<ref name="pmid16820386">Template:Cite journal</ref> aorta,<ref name="pmid15310302">Template:Cite journal</ref> and brachioradial artery.<ref name="pmid14715193">Template:Cite journal</ref> This change in the vascular tone is secondary to endothelial dysfunction.<ref name="pmid8901658"/> In addition, children with Kawasaki disease, with or without coronary artery complications, may have a more adverse cardiovascular risk profile later in life,<ref name="pmid14715193" /> and may benefit from long term monitoring and prevention approaches to both detect cardiovascular disease early such as thrombosis or stenosis and prevent onset.<ref name="Brogan2020" /> Examples of prevention approaches include lipid lowering medications, blood pressure medication, smoking cessation, and healthy active living.<ref name="Brogan2020" />

Gastrointestinal complications in Kawasaki disease are similar to those observed in Henoch–Schönlein purpura,<ref name="pmid21691693" /> such as: intestinal obstruction,<ref name="pmid16150324">Template:Cite journal</ref> colon swelling,<ref name="pmid18756065">Template:Cite journal</ref> intestinal ischemia,<ref name="pmid11283899">Template:Cite journal</ref> intestinal pseudo-obstruction,<ref name="pmid15121996">Template:Cite journal</ref> and acute abdomen.<ref name="pmid12838207">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Eye changes associated with the disease have been described since the 1980s, being found as uveitis, iridocyclitis, conjunctival hemorrhage,<ref name="pmid7201245">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid7299613">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid15206604">Template:Cite journal</ref> optic neuritis,<ref name="pmid21691693" /> amaurosis, and ocular artery obstruction.<ref name="pmid17913174">Template:Cite journal</ref> It can also be found as necrotizing vasculitis, progressing into peripheral gangrene.<ref name="pmid1571415">Template:Cite journal</ref>

The neurological complications per central nervous system lesions are increasingly reported.<ref name="pmid11587880">Template:Cite journal</ref> The neurological complications found are meningoencephalitis,<ref name="pmid2223179">Template:Cite journal</ref> subdural effusion,<ref name="pmid3344468">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid11589317">Template:Cite journal</ref> cerebral hypoperfusion,<ref name="pmid9660380">Template:Cite journal</ref> cerebral ischemia and infarct,<ref name="pmid1622525">Template:Cite journal</ref> cerebellar infarction,<ref name="pmid15967620">Template:Cite journal</ref> manifesting with seizures, chorea, hemiplegia, mental confusion, lethargy and coma,<ref name="pmid21691693" /> or even a cerebral infarction with no neurological manifestations.<ref name="pmid1622525" /> Other neurological complications from cranial nerve involvement are reported as ataxia,<ref name="pmid21691693" /> facial palsy,<ref name="pmid18678602">Template:Cite journal</ref> and sensorineural hearing loss.<ref name="pmid11562886">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid14647816">Template:Cite journal</ref> Behavioral changes are thought to be caused by localised cerebral hypoperfusion,<ref name="pmid9660380"/> can include attention deficits, learning deficits, emotional disorders (emotional lability, fear of night, and night terrors), and internalization problems (anxious, depressive or aggressive behavior).<ref name="pmid15916701">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid10807296">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Causes

The specific cause of Kawasaki disease is unknown.<ref name="pmid18364728">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="AHA: Kawasaki Disease">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="kawasaki-disease-causes">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name=Marrani2018/> A plausible explanation is that it may be caused by an infection that triggers an inappropriate immunologic cascade in a small number of genetically predisposed children.<ref name=McC2017/><ref name=Rowley2018>Template:Cite journal</ref> The pathogenesis is complex and incompletely understood.<ref name=Lo2020>Template:Cite journal</ref> Various explanations exist.<ref name=Marrani2018/> (See Classification)

Circumstantial evidence points to an infectious cause.<ref name="pmid19075496">Template:Cite journal</ref> Since recurrences are unusual in Kawasaki disease, it is thought that the trigger is more likely to be represented by a single pathogen, rather than a range of viral or bacterial agents.<ref name=Rowley2018a>Template:Cite journal</ref> Various candidates have been implicated, including upper respiratory tract infection by some novel RNA virus.<ref name=McC2017/> Despite intensive search, no single pathogen has been identified.<ref name=Lo2020/> There has been debate as to whether the infectious agent might be a superantigen (i.e. one commonly associated with excessive immune system activation).<ref name=Marrani2018/><ref name="pmid=11964855">Template:Cite journal</ref> Current consensus favors an excessive immunologic response to a conventional antigen which usually provides future protection.<ref name=McC2017/> Research points to an unidentified ubiquitous virus,<ref name=Rowley2020>Template:Cite journal</ref> possibly one that enters through the respiratory tract.<ref name=Soni2020>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Seasonal trends in the appearance of new cases of Kawasaki disease have been linked to tropospheric wind patterns, which suggests wind-borne transport of something capable of triggering an immunologic cascade when inhaled by genetically susceptible children.<ref name=McC2017/> Winds blowing from central Asia correlate with numbers of new cases of Kawasaki disease in Japan, Hawaii, and San Diego.<ref name=Rod>Template:Cite journal</ref> These associations are themselves modulated by seasonal and interannual events in the El Niño–Southern Oscillation in winds and sea surface temperatures over the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean.<ref name=Ballester>Template:Cite journal</ref> Efforts have been made to identify a possible pathogen in air-filters flown at altitude above Japan.<ref name=Frazer>Template:Cite journal</ref> One source has been suggested in northeastern China.<ref name=McC2017/><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Genetics

Genetic susceptibility is suggested by increased incidence among children of Japanese descent around the world, and also among close and extended family members of affected people.<ref name=McC2017/> Genetic factors are also thought to influence development of coronary artery aneurysms and response to treatment.<ref name=Dietz2017>Template:Cite journal</ref> The exact genetic contribution remains unknown.<ref name=Son2016>Template:Cite book</ref> Genome-wide association studies and studies of individual candidate genes have together helped identify specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), mostly found in genes with immune regulatory functions.<ref name=Dietz2017/> The associated genes and their levels of expression appear to vary among different ethnic groups, both with Asian and non-Asian backgrounds.<ref name=Elakabawi2020>Template:Cite journal</ref>

SNPs in FCGR2A, CASP3, BLK, ITPKC, CD40 and ORAI1 have all been linked to susceptibility, prognosis, and risk of developing coronary artery aneurysms.<ref name=Elakabawi2020/> Various other possible susceptibility genes have been proposed, including polymorphisms in the HLA region, but their significance is disputed.<ref name=Son2016/> Genetic susceptibility to Kawasaki disease appears complex.<ref name=Galeotti2016>Template:Cite journal</ref> Gene–gene interactions also seem to affect susceptibility and prognosis.<ref name=Elakabawi2020/> At an epigenetic level, altered DNA methylation has been proposed as an early mechanistic factor during the acute phase of the disease.<ref name=Elakabawi2020/>

Diagnosis

| Criteria for diagnosis |

|---|

| Fever of ≥5 days' duration associated with at least four† of these five changes |

| Bilateral nonsuppurative conjunctivitis |

| One or more changes of the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract, including throat redness, dry cracked lips, red lips, and "strawberry" tongue |

| One or more changes of the arms and legs, including redness, swelling, skin peeling around the nails, and generalized peeling |

| Polymorphous rash, primarily truncal |

| Large lymph nodes in the neck (>15 mm in size) |

| Disease cannot be explained by some other known disease process |

| †A diagnosis of Kawasaki disease can be made if fever and only three changes are present if coronary artery disease is documented by two-dimensional echocardiography or coronary angiography. |

| Source: Nelson's essentials of pediatrics,<ref name="isbn1-4160-0159-X">Template:Cite book</ref> Review<ref name="pmid16322081">Template:Cite journal</ref> |

Since no specific laboratory test exists for Kawasaki disease, diagnosis must be based on clinical signs and symptoms, together with laboratory findings.<ref name=SHARE2019>Template:Cite journal</ref> Timely diagnosis requires careful history-taking and thorough physical examination.<ref name=Newburger2016>Template:Cite journal</ref> Establishing the diagnosis is difficult, especially early in the course of the illness, and frequently children are not diagnosed until they have seen several health-care providers. Many other serious illnesses can cause similar symptoms, and must be considered in the differential diagnosis, including scarlet fever, toxic shock syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and childhood mercury poisoning (infantile acrodynia).<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Classically, five days of fever<ref name="urlKawasaki Disease - June 1999 - American Academy of Family Physicians">Template:Cite journal</ref> plus four of five diagnostic criteria must be met to establish the diagnosis. The criteria are:<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

- erythema of the lips or oral cavity or cracking of the lips

- rash on the trunk

- swelling or erythema of the hands or feet

- red eyes (conjunctival injection)

- swollen lymph node in the neck of at least 15 mm

Many children, especially infants, eventually diagnosed with Kawasaki disease, do not exhibit all of the above criteria. In fact, many experts now recommend treating for Kawasaki disease even if only three days of fever have passed and at least three diagnostic criteria are present, especially if other tests reveal abnormalities consistent with Kawasaki disease. In addition, the diagnosis can be made purely by the detection of coronary artery aneurysms in the proper clinical setting.Template:Citation needed

Investigations

A physical examination will demonstrate many of the features listed above.

Blood tests

- Complete blood count may reveal normocytic anemia and eventually thrombocytosis.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate will be elevated.

- C-reactive protein will be elevated.

- Liver function tests may show evidence of hepatic inflammation and low serum albumin levels.<ref name="pmid20491705">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Other optional tests include:

- Electrocardiogram may show evidence of ventricular dysfunction or, occasionally, arrhythmia due to myocarditis.

- Echocardiogram may show subtle coronary artery changes or, later, true aneurysms.

- Ultrasound or computerized tomography may show hydrops (enlargement) of the gallbladder.

- Urinalysis may show white blood cells and protein in the urine (pyuria and proteinuria) without evidence of bacterial growth.

- Lumbar puncture may show evidence of aseptic meningitis.

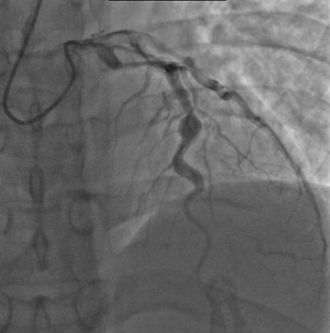

- Angiography was historically used to detect coronary artery aneurysms, and remains the gold standard for their detection, but is rarely used today unless coronary artery aneurysms have already been detected by echocardiography.

Biopsy is rarely performed, as it is not necessary for diagnosis.<ref name=StatPearls/>

Subtypes

Based on clinical findings, a diagnostic distinction may be made between the "classic" or "typical" presentation of Kawasaki disease and "incomplete" or "atypical" presentation of a "suspected" form of the disease.<ref name=McC2017/> Regarding incomplete/atypical presentation, American Heart Association guidelines state that Kawasaki disease "should be considered in the differential diagnosis of prolonged unexplained fever in childhood associated with any of the principal clinical features of the disease, and the diagnosis can be considered confirmed when coronary artery aneurysms are identified in such patients by echocardiography."<ref name=McC2017/>

A further distinction between incomplete and atypical subtypes may also be made in the presence of non-typical symptoms.<ref name=Marchesi2018>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Case definition

For study purposes, including vaccine safety monitoring, an international case definition has been proposed to categorize 'definite' (i.e. complete/incomplete), 'probable' and 'possible' cases of Kawasaki disease.<ref name=Brighton2016>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Differential diagnosis

The broadness of the differential diagnosis is a challenge to timely diagnosis of Kawasaki disease.<ref name=SHARE2019/> Infectious and noninfectious conditions requiring consideration include: measles and other viral infections (e.g. adenovirus, enterovirus); staphylococcal and streptococcal toxin-mediated diseases such as scarlet fever and toxic shock syndrome; drug hypersensitivity reactions (including Stevens Johnson syndrome); systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis; Rocky Mountain spotted fever or other rickettsial infections; and leptospirosis.<ref name=McC2017/> Infectious conditions that can mimic Kawasaki disease include periorbital cellulitis, peritonsillar abscess, retropharyngeal abscess, cervical lymphadenitis, parvovirus B19, mononucleosis, rheumatic fever, meningitis, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and Lyme disease.<ref name=StatPearls>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Kawasaki-like disease temporally associated with COVID-19

In 2020, reports of a Kawasaki-like disease following exposure to SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, emerged in the US and Europe.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name=Galeotti2020/> The World Health Organization is examining possible links with COVID-19.<ref name=WHO2020>Template:Cite web</ref> This emerging condition was named "paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome" by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health,<ref name=RCP2020>Template:Citation</ref> and "multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children" by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.<ref name=CDC2020>Template:Cite web</ref> Guidance for diagnosis and reporting of cases has been issued by these organizations.<ref name=RCP2020/><ref name=WHO2020/><ref name=CDC2020/>

Several reported cases suggest that this Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome is not limited to children; there is the possibility of an analogous disease in adults, which has been termed MIS-A. Some suspected patients have presented with positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 and reports suggest intravenous immunoglobulin, anticoagulation, tocilizumab, plasmapheresis and steroids are potential treatments.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Classification

Debate has occurred about whether Kawasaki disease should be viewed as a characteristic immune response to some infectious pathogen, as an autoimmune process, or as an autoinflammatory disease (i.e. involving innate rather than adaptive immune pathways).<ref name=Marrani2018>Template:Cite journal</ref> Overall, immunological research suggests that Kawasaki disease is associated with a response to a conventional antigen (rather than a superantigen) that involves both activation of the innate immune system and also features of an adaptive immune response.<ref name=McC2017/><ref name=McCrindle2020>Template:Cite journal</ref> Identification of the exact nature of the immune process involved in Kawasaki disease could help guide research aimed at improving clinical management.<ref name=Marrani2018/>

Inflammation, or vasculitis, of the arteries and veins occurs throughout the body, usually caused by increased production of the cells of the immune system to a pathogen, or autoimmunity.<ref name="pmid18524103"/> Systemic vasculitides may be classified according to the type of cells involved in the proliferation, as well as the specific type of tissue damage occurring within the vein or arterial walls.<ref name="pmid18524103"/> Under this classification scheme for systemic vasculitis, Kawasaki disease is considered to be a necrotizing vasculitis (also called necrotizing angiitis), which may be identified histologically by the occurrence of necrosis (tissue death), fibrosis, and proliferation of cells associated with inflammation in the inner layer of the vascular wall.<ref name="pmid18524103">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Other diseases involving necrotizing vasculitis include polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.<ref name="pmid18524103"/>

Kawasaki disease may be further classified as a medium-sized vessel vasculitis, affecting medium- and small-sized blood vessels,<ref name="pmid3766134">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid19946711">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid17274537">Template:Cite journal</ref> such as the smaller cutaneous vasculature (veins and arteries in the skin) that range from 50 to 100 μm in diameter.<ref name="pmid19851663">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid19377760">Template:Cite journal</ref> Kawasaki disease is also considered to be a primary childhood vasculitis, a disorder associated with vasculitis that mainly affects children under the age of 18.<ref name="pmid16322081" /><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> A recent, consensus-based evaluation of vasculitides occurring primarily in children resulted in a classification scheme for these disorders, to distinguish them and suggest a more concrete set of diagnostic criteria for each.<ref name="pmid16322081" /> Within this classification of childhood vasculitides, Kawasaki disease is, again, a predominantly medium-sized vessel vasculitis.<ref name="pmid16322081" />

It can also be classed as an autoimmune form of vasculitis.<ref name=Kim2006/> It is not associated with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, unlike other vasculitic disorders associated with them (such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis).<ref name="pmid18524103"/><ref name="pmid17408915">Template:Cite journal</ref> This form of categorization is relevant for appropriate treatment.<ref name="pmid11123094">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Treatment

Children with Kawasaki disease should be hospitalized and cared for by a physician who has experience with this disease. In an academic medical center, care is often shared between pediatric cardiology, pediatric rheumatology, and pediatric infectious disease specialists (although no specific infectious agent has yet been identified).<ref name="childrens" /> To prevent damage to coronary arteries, treatment should be started immediately following the diagnosis.Template:Citation needed

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is the standard treatment for Kawasaki disease<ref name="pmid14584002">Template:Cite journal</ref> and is administered in high doses with marked improvement usually noted within 24 hours. If the fever does not respond, an additional dose may be considered. In rare cases, a third dose may be given. IVIG is most useful within the first seven days of fever onset, to prevent coronary artery aneurysm. IVIG given within the first 10 days of the disease reduces the risk of damage to the coronary arteries in children, without serious adverse effects.<ref name="pmid14584002" /> A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that no prediction models of IVIG resistance in patients with Kawasaki disease could accurately distinguish the resistance.<ref name="pmid37092277">Template:Cite journal</ref> The largest clinical study to date on treatment of resistant Kawasaki disease has shown that infliximab is more effective and safer than a second dose of IVIG in treating children with IVIG-resistant Kawasaki Disease, offering faster fever resolution and reduced hospitalization times without significant adverse events.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Salicylate therapy, particularly aspirin, remains an important part of the treatment (though questioned by some)<ref name="pmid15545617">Template:Cite journal</ref> but salicylates alone are not as effective as IVIG. There is limited evidence to indicate whether children should continue to receive salicylate as part of their treatment.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Aspirin therapy is started at high doses until the fever subsides, and then is continued at a low dose when the patient returns home, usually for two months to prevent blood clots from forming. Except for Kawasaki disease and a few other indications, aspirin is otherwise normally not recommended for children due to its association with Reye syndrome. Because children with Kawasaki disease will be taking aspirin for up to several months, vaccination against varicella and influenza is required, as these infections are most likely to cause Reye syndrome.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

High-dose aspirin is associated with anemia and does not confer benefit to disease outcomes.<ref name="pmid26658843">Template:Cite journal</ref>

About 15-20% of children following the initial IVIG infusion show persistent or recurrent fever and are classified as IVIG-resistant. While the use of TNF alpha blockers (TNF-α) may reduce treatment resistance and the infusion reaction after treatment initiation, further research is needed.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Due to the potential involvement of the upregulated calcium-nuclear factor of activated T cells pathway in the development of the disease, a 2019 study found that the combination of ciclosporin and IVIG infusion can suppress coronary artery abnormalities. Further research is needed to determine which patients would respond best to this treatment.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Corticosteroids have also been used,<ref name="pmid12838187">Template:Cite journal</ref> especially when other treatments fail or symptoms recur, but in a randomized controlled trial, the addition of corticosteroid to immune globulin and aspirin did not improve outcome.<ref name="pmid17301297">Template:Cite journal</ref> Additionally, corticosteroid use in the setting of Kawasaki disease is associated with increased risk of coronary artery aneurysm, so its use is generally contraindicated in this setting. In cases of Kawasaki disease refractory to IVIG, cyclophosphamide and plasma exchange have been investigated as possible treatments, with variable outcomes. However, a Cochrane review published in 2017 (updated in 2022) found that, in children, the use of corticosteroids in the acute phase of KD was associated with improved coronary artery abnormalities, shorter hospital stays, a decreased duration of clinical symptoms, and reduced inflammatory marker levels. Patient populations based in Asia, people with higher risk scores, and those receiving longer steroid treatment may have greater benefit from steroid use.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Prognosis

With early treatment, rapid recovery from the acute symptoms can be expected, and the risk of coronary artery aneurysms is greatly reduced. Untreated, the acute symptoms of Kawasaki disease are self-limited (i.e. the patient will recover eventually), but the risk of coronary artery involvement is much greater, even many years later. Many cases of myocardial infarction in young adults have now been attributed to Kawasaki disease that went undiagnosed during childhood.<ref name=McC2017/> Overall, about 2% of patients die from complications of coronary vasculitis.Template:Citation needed

Laboratory evidence of increased inflammation combined with demographic features (male sex, age less than six months or greater than eight years) and incomplete response to IVIG therapy create a profile of a high-risk patient with Kawasaki disease.<ref name="pmid3950818" /><ref name="pmid9605052">Template:Cite journal</ref> The likelihood that an aneurysm will resolve appears to be determined in large measure by its initial size, in which the smaller aneurysms have a greater likelihood of regression.<ref name="pmid3423060">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid4061324">Template:Cite journal</ref> Other factors are positively associated with the regression of aneurysms, including being younger than a year old at the onset of Kawasaki disease, fusiform rather than saccular aneurysm morphology, and an aneurysm location in a distal coronary segment.<ref name="pmid3802442" /> The highest rate of progression to stenosis occurs among those who develop large aneurysms.<ref name=Kim2006 /> The worst prognosis occurs in children with giant aneurysms.<ref name="pmid3668739">Template:Cite journal</ref> This severe outcome may require further treatment such as percutaneous transluminal angioplasty,<ref name="pmid11737728">Template:Cite journal</ref> coronary artery stenting,<ref name="pmid10931409">Template:Cite journal</ref> bypass grafting,<ref name="pmid12544719">Template:Cite journal</ref> and even cardiac transplantation.<ref name="pmid9310527">Template:Cite journal</ref>

A relapse of symptoms may occur soon after initial treatment with IVIG. This usually requires rehospitalization and retreatment. Treatment with IVIG can cause allergic and nonallergic acute reactions, aseptic meningitis, fluid overload, and rarely, other serious reactions. Overall, life-threatening complications resulting from therapy for Kawasaki disease are exceedingly rare, especially compared with the risk of nontreatment. Evidence indicates Kawasaki disease produces altered lipid metabolism that persists beyond the clinical resolution of the disease.Template:Citation needed

Rarely, recurrence can occur in Kawasaki disease with or without treatment.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Epidemiology

Kawasaki disease affects boys more than girls, with people of Asian ethnicity, particularly Japanese people. The higher incidence in Asian populations is thought to be linked to genetic susceptibility.<ref name=Onouchi2018>Template:Cite journal</ref> Incidence rates vary between countries.

Currently, Kawasaki disease is the most commonly diagnosed pediatric vasculitis in the world. By far, the highest incidence of Kawasaki disease occurs in Japan, with the most recent study placing the attack rate at 218.6 per 100,000 children less than five years of age (about one in 450 children). At this present attack rate, more than one in 150 children in Japan will develop Kawasaki disease during their lifetimes.Template:Citation needed

However, its incidence in the United States is increasing. Kawasaki disease is predominantly a disease of young children, with 80% of patients younger than five years of age. About 2,000–4,000 cases are identified in the U.S. each year (9 to 19 per 100,000 children younger than five years of age).<ref name="childrens">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="urlKawasaki Disease - Signs and Symptoms">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="CDC 2014">Template:Cite web</ref> In the continental United States, Kawasaki disease is more common during the winter and early spring, boys with the disease outnumber girls by ≈1.5–1.7:1, and 76% of affected children are less than 5 years of age.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

In the United Kingdom, before 2000, it was diagnosed in fewer than one in every 25,000 people per year.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Incidence of the disease doubled from 1991 to 2000, however, with four cases per 100,000 children in 1991 compared with a rise of eight cases per 100,000 in 2000.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> By 2017, this figure had risen to 12 in 100,000 people with 419 diagnosed cases of Kawasaki disease in the United Kingdom.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

In Japan, the rate is 240 in every 100,000 people.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Coronary artery aneurysms due to Kawasaki disease are believed to account for 5% of acute coronary syndrome cases in adults under 40 years of age.<ref name=McC2017/>

History

The disease was first reported by Tomisaku Kawasaki in a four-year-old child with a rash and fever at the Red Cross Hospital in Tokyo in January 1961, and he later published a report on 50 similar cases.<ref name="pmid6062087" /> Later, Kawasaki and colleagues were persuaded of definite cardiac involvement when they studied and reported 23 cases, of which 11 (48%) patients had abnormalities detected by an electrocardiogram.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> In 1974, the first description of this disorder was published in the English-language literature.<ref name="pmid4153258">Template:Cite journal</ref> In 1976, Melish et al. described the same illness in 16 children in Hawaii.<ref name="pmid7134">Template:Cite journal</ref> Melish and Kawasaki had independently developed the same diagnostic criteria for the disorder, which are still used today to make the diagnosis of classic Kawasaki disease.

A question was raised whether the disease only started during the period between 1960 and 1970, but later a preserved heart of a seven-year-old boy who died in 1870 was examined and showed three aneurysms of the coronary arteries with clots, as well as pathologic changes consistent with Kawasaki disease.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Kawasaki disease is now recognized worldwide. Why cases began to emerge across all continents around the 1960s and 1970s is unclear.<ref name=Burns2018>Template:Cite journal</ref> Possible explanations could include confusion with other diseases such as scarlet fever, and easier recognition stemming from modern healthcare factors such as the widespread use of antibiotics.<ref name=Burns2018/> In particular, old pathological descriptions from Western countries of infantile polyarteritis nodosa coincide with reports of fatal cases of Kawasaki disease.<ref name=McC2017/>

In the United States and other developed nations, Kawasaki disease appears to have replaced acute rheumatic fever as the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

References

External links

Template:Medical condition classification and resources Template:Systemic vasculitis Template:Authority control