Hill of Tara

Template:Short description Template:Distinguish Template:Use Hiberno-English Template:Use dmy dates Template:Infobox ancient site

The Hill of Tara (Template:Langx or Template:Lang)<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> is a hill and ancient ceremonial and burial site near Skryne in County Meath, Ireland. Tradition identifies the hill as the inauguration place and seat of the High Kings of Ireland; it also appears in Irish mythology. Tara consists of numerous monuments and earthworks—dating from the Neolithic to the Iron Age—including a passage tomb (the "Mound of the Hostages"), burial mounds, round enclosures, a standing stone (believed to be the Lia Fáil or "Stone of Destiny"), and a ceremonial avenue.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> There is also a church and graveyard on the hill. Tara forms part of a larger ancient landscape and Tara itself is a protected national monument under the care of the Office of Public Works, an agency of the Irish Government.

Name

The name Tara is an anglicization of the Irish name Template:Lang or Template:Lang ('hill of Tara'). It is also known as Template:Lang ('Tara of the kings'), and formerly also Template:Lang ('the grey ridge').Template:Sfn The Old Irish form is Template:Lang. It is believed this comes from Proto-Celtic Template:Lang and means a 'sanctuary' or 'sacred space' cut off for ceremony, cognate with the Greek Template:Lang (Template:Lang) and Latin Template:Lang. Another suggestion is that it means "a height with a view".<ref>Koch, John T. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2006. p.1663</ref><ref>Halpin, Andrew. Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide to Sites from Earliest Times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press, 2006. p.341</ref>

Early history

Ancient monuments

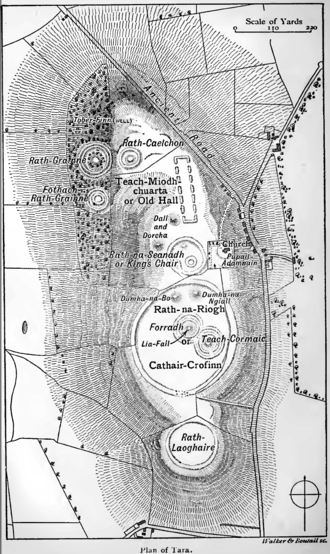

The remains of twenty ancient monuments are visible, and at least three times that many have been found through geophysical surveys and aerial photography.<ref name="halpin-newman">Andrew Halpin and Conor Newman. Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide to Sites from Earliest Times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press, 2006. pp.341-347</ref>

The oldest visible monument is Template:Lang (the 'Mound of the Hostages'),<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> a Neolithic passage tomb built around 3,200 BC.<ref name="quinn">Quinn, Colin. "Returning and Reuse: Diachronic Perspectives on Multi-Component Cemeteries and Mortuary Politics at Middle Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Tara, Ireland" Template:Webarchive. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, issue 37 (2015). pp.1-18</ref> It holds the remains of hundreds of people, most of which are cremated bones. In the Neolithic, it was the communal tomb of a single community for about a century, during which there were almost 300 burials. Almost a millennium later, in the Bronze Age, there were a further 33 burials – first in the passage and then in the mound around it.<ref name="quinn"/> During this time, only certain high-status individuals were buried there. At first, it was the tomb of one community, but later multiple communities came together to bury their elite there.<ref name="quinn"/> The last burial was a full body burial of a young man of high status, with an ornate necklace and dagger.<ref name="halpin-newman"/> Two gold torcs were found there dating to around 2000 BC.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

During the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age, a huge double timber circle or "wood henge" was built on the hilltop.<ref>"Woodhenge - Tara" Template:Webarchive. Knowth.com.</ref> It was 250m in diameter and surrounded the Mound of the Hostages.<ref name="halpin-newman"/> At least six smaller burial mounds were built in an arc around this timber circle, including those known as Template:Lang, Template:Lang, Template:Lang ('Mound of the Mercenary Women') and Template:Lang ('Mound of the Cow'). The timber circle was eventually either removed or decayed, and the burial mounds are barely visible today.<ref name="newman2007">Newman, Conor (2007). "Procession and Symbolism at Tara" Template:Webarchive. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 26(4), pp.415-438</ref>

There are several large round enclosures on the hill, which were built in the Iron Age.<ref name="halpin-newman"/> The biggest and most central of these is Ráth na Ríogh (the Enclosure of the Kings), which measures Template:Convert in circumference, Template:Convert north-south by Template:Convert east-west, with an inner ditch and outer bank. It is dated to the 1st century BC and was originally marked out by a stakewall.<ref name="halpin-newman"/> Human burials, and a high concentration of horse and dog bones, were found in the ditch.<ref name="halpin-newman"/> Within the Template:Lang is the Mound of the Hostages and two round, double-ditched enclosures which together make a figure-of-eight shape. One is Template:Lang ('Cormac's House') and the other is the Template:Lang or Royal Seat, which incorporates earlier burial mounds. On top of the Template:Lang is a standing stone, which is believed to be the Template:Lang ('Stone of Destiny') at which the High Kings were crowned. According to legend, the stone would let out a roar when the rightful king touched it. It is believed that the stone originally lay beside or on top of the Mound of the Hostages.<ref name="halpin-newman"/>

Just to the north of Template:Lang, is Template:Lang (the 'Rath of the Synods'), which was built in the middle of the former "wood henge".<ref name="halpin-newman"/> It is a round enclosure with four rings of ditches and banks, and incorporates earlier burial mounds. It was re-modelled several times and once had a large timber building inside it, resembling the one at Navan.<ref name="Bradley">Bradley, Richard. The Past in Prehistoric Societies. Psychology Press, 2002. p.145</ref> It was occupied between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, and Roman artefacts were also found there.<ref name="halpin-newman"/> It was badly mutilated in the early 20th century by British Israelites searching for the Ark of the Covenant.<ref name="halpin-newman"/>

The other round enclosures are Template:Lang ('Laoghaire's Fort', where the eponymous king is said to have been buried) at the southern edge of the hill, and the Template:Lang ('Sloping Trenches' or 'Sloping Graves') at the northwestern edge, which includes Template:Lang and Template:Lang. The Template:Lang are burial mounds with ring ditches around them which sit on a slope.<ref name="halpin-newman"/>

At the northern end of the hill is Template:Lang or 'Banqueting Hall'. This was likely the ceremonial avenue leading to the hilltop and seems to have been one of the last monuments built.<ref name="halpin-newman"/><ref name="newman2007"/>

Half a mile south of the Hill of Tara is another large round enclosure known as Rath Meave, which refers to the legendary figure Medb or Medb Lethderg.

Annals

In the Annals of Inisfallen (AI980.4) is a description of the Battle of Tara between Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill and the son of Amlaíb Cuarán.

Church

A church, called Saint Patrick's, is on the eastern side of the hilltop. The "Rath of the Synods" has been partly destroyed by its churchyard.<ref name=roughguide>The Hill of Tara Template:Webarchive. Rough Guides. Retrieved 24 March 2013.</ref> The modern church was built in 1822–23 on the site of an earlier one.<ref name=church1>Draft Tara Skryne Landscape Conservation Area Template:Webarchive. Meath County Council. 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2013.</ref>

The earliest evidence of a church at Tara is a charter dating from the 1190s. In 1212, this church was "among the possessions confirmed to the Knights Hospitallers of Saint John of Kilmainham by Pope Innocent III".<ref name=church1/> A 1791 illustration shows the church building internally divided into a nave and chancel, with a bell-tower over the western end. A stump of wall marks the site of the old church today, but some of its stonework was re-used in the current church.

The building is now used as a visitor centre, operated by the Office of Public Works (OPW), an agency of the Irish Government.<ref name=church1/>

The Five Roads of Tara

According to legend, five ancient roads or Template:Lang meet at Tara, linking it with all the provinces of Ireland. The earliest reference to the five roads of Tara was in the tale Template:Lang (The Destruction of Da Derga's Hall).<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

The five roads are said to be:

- Template:Lang, which went west towards Lough Owel, then to Rathcroghan.

- Template:Lang, which went to Slane, then to Navan Fort, ending at Dunseverick.

- Template:Lang, which went through Dublin and through the old district of Cualann towards Waterford.

- Template:Lang, which went towards and through Ossory.

- Template:Lang ('Great Highway'), which roughly followed the Esker Riada to County Galway.

Significance

The passage of the Mound of the Hostages is aligned with the sunrise around the times of Samhain (the Gaelic festival marking the start of winter) and Imbolc (the festival marking the start of spring).<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> The passage is shorter than monuments like Newgrange, making it less precise in providing alignments with the Sun, but Martin Brennan writes in The Stones of Time that "daily changes in the position of a 13-foot long sunbeam are more than adequate to determine specific dates".<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Early Irish literature records that a royal gathering called the 'feast of Tara' (feis Temro) was held there at Samhain.<ref name="O hOgain"/>

By the beginning of Ireland's historical period, Tara had become the seat of a sacral kingship.<ref name="O hOgain">Template:Cite book</ref> Historian Dáibhí Ó Cróinín writes that Tara "possessed an aura that seemed to set it above" the other royal seats.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> It is recorded as the seat of the High King of Ireland (Ard Rí) and is "central to most of the great drama in early Irish literature".<ref name="O hOgain"/> Various medieval king lists traced a line of High Kings far into the past. However, John T. Koch explains: "Although the kingship of Tara was a special kingship whose occupants had aspirations towards supremacy among the kings of Ireland, in political terms it is unlikely that any king had sufficient authority to dominate the whole island before the 9th century".<ref name="Koch">Template:Cite book</ref>

Irish legend says that the Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny) at Tara was brought to Ireland by the divine Tuatha Dé Danann, and that it would cry out under the foot of the true king.<ref name="O hOgain"/> Medb Lethderg was the sovereignty goddess of Tara.<ref name="O hOgain"/> The cult of the sacral kingship of Tara is reflected in the legends of High King Conaire Mór, while another legendary High King, Cormac mac Airt, is presented as the ideal king.<ref name="O hOgain"/> The reign of Diarmait mac Cerbaill, a historical king of Tara in the sixth century, was seen as particularly important by medieval writers. Although he was probably pagan, he was also influenced by Christian leaders and "stood chronologically between two worlds, the ancient pagan one and the new Christian one".<ref>Ó hÓgáin, p.159</ref>

Tara was probably controlled by the Érainn before it was seized by the Laigin in the third century.<ref name="O hOgain"/> Niall of the Nine Hostages displaced the Laigin from Tara in the fifth century and it became the ceremonial seat of the Uí Néill.<ref name="O hOgain"/> The kingship of Tara alternated between the Southern and Northern Uí Néill until the eleventh century. After this, control of Dublin, Limerick, and Waterford became more important to a would-be High King than control of Tara.<ref name="Koch"/>

According to Irish mythology, during the third century a great battle known as the Cath Gabhra took place between High King Cairbre Lifechair, and the Fianna led by Fionn Mac Cumhaill. The Fianna were heavily defeated; many of the graves of the Fianna covered the Rath of the Gabhra, most notably the grave of Oscar, son of Oisín.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Later history

During the rebellion of 1798, United Irishmen formed a camp on the hill but were attacked and defeated by British troops<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> on 26 May 1798 and the Template:Lang was allegedly moved to commemorate the 400 rebels who died on the hill that day.

In 1843, the Irish nationalist leader Daniel O'Connell hosted a peaceful political demonstration at Tara in favour of Irish self-governance which drew over 750,000 people, highlighting the lasting significance of Tara.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

British Prime Minister John Russell inherited the Tara estate during the 19th century. At the turn of the 20th century, Tara was vandalised by British Israelists who thought that the British were part of the Lost Tribes of Israel and that the hill contained the Ark of the Covenant.<ref name="Carew">Template:Cite book</ref> A group of British Israelists, led by retired Anglo-Indian judge Edward Wheeler Bird, set about excavating the site having paid off the landowner, Gustavus Villiers Briscoe. Irish cultural nationalists held a mass protest over the destruction of the national heritage site, including Douglas Hyde, Arthur Griffith, Maud Gonne, George Moore and W. B. Yeats. Hyde tried to interrupt the dig but was ordered away by a man wielding a rifle. Maud Gonne made a more flamboyant protest by relighting an old bonfire that Briscoe had lit to celebrate the coronation of Edward VII. She began to sing Thomas Davis's song "A Nation Once Again" by the fire, much to the consternation of the landlord and the police.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

The Irish government bought the southern part of the hill in 1952, and the northern part in 1972.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

The religious order Missionary Society of St. Columban had its international headquarters at Dalgan Park, just north of the Hill of Tara. The order was named after the Saint who was born in the Ancient Kingdom of Meath. The land Dalgan Park lies on was once owned by the kings of Tara. The seminary is also situated on the path of the Template:Lang, one of the five ancient roads that meet at Tara.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Motorway development

The M3 motorway passes through the Tara-Skryne Valley – as did the existing N3 road. Protesters argue that since the Tara Discovery Programme started in 1992, there is an appreciation that the Hill of Tara is just the central complex of a wider landscape.<ref name="Newman_bk_2015">Conor Newman (2015) 'In the way of development: Tara, the M3 and the Celtic Tiger', in Meade, R. and Dukelow, F. (eds.) Defining Events: Power, resistance and identity in twenty-first-century Ireland, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 32–50.</ref> The distance between the motorway and the hill is Template:Convert – it intersects the old N3 at the Blundelstown interchange between the Hill of Tara and the Hill of Skryne. Protesters said that an alternative route about Template:Convert west of Tara would have been straighter, cheaper and less destructive.<ref name="IrishTimes-2007-05-26">Template:Cite news</ref><ref name="WashingtonPost-2005-01-22">Template:Cite news</ref> On Sunday 23 September 2007 over 1500 people met on the Hill of Tara to take part in a human sculpture representing a harp and spelling out the words "SAVE TARA VALLEY" as a call for the re-routing of the M3 motorway away from Tara. Actors Stuart Townsend and Jonathan Rhys Meyers attended this event.<ref name="Indymedia Ireland-2005-09-24">Template:Cite news</ref> There was also a letter writing campaign to preserve the Hill of Tara.<ref>"The Hill of Tara". Sacred Sites International Foundation. Template:Webarchive</ref>

The Hill of Tara was included in the World Monuments Fund's 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in the world.<ref>Template:Cite web World Monuments Fund.</ref> The following year it was included in a list of the 15 must-see endangered cultural treasures by the Smithsonian Institution.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

The motorway project proceeded, and the road was opened in June 2010.<ref name="Newman_bk_2015"/>

Gallery

-

Hill of Tara, Lia Fáil and surrounding landscape

-

High Cross

-

Church

-

Summit

-

Aerial photograph

See also

- Template:Annotated link, historic residence of Swedish kings of the legendary Yngling dynasty

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link, c. 7th century AD pennanular brooch named after, but not from Tara

- Template:Annotated link, Book of Psalms, discovered 2006

- Template:Annotated link, Close to Tara is the Hill of Ward, it's associated with the mythological druidess Tlachtga

- Template:Annotated link, a druidic site associated with the festival of Bealtaine

References

Sources

Further reading

- Template:Citation, alt link

- Template:Citation, alt link

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

External links

- Hill of Tara at Megalithic Ireland

- Aerial photos of the monuments

- Heritage of Ireland, Tara

- Boyne Valley Tourist Portal – Information on Tara

- The Hill of Tara page on Mythical Ireland

- Template:Citation

Template:Irish mythology (mythological) Template:Mountains and hills of Leinster Template:Authority control

- Pages with broken file links

- Prehistoric sites in Ireland

- Archaeological sites in County Meath

- Mountains and hills of County Meath

- Tourist attractions in County Meath

- National monuments in County Meath

- Royal sites of Ireland

- Former populated places in Ireland

- Sacred mountains of Ireland

- Irish legends

- John Russell, 1st Earl Russell