Nubians

Template:Short description Template:About Template:Pp-move Template:Use dmy dates Template:Infobox ethnic group

Nubians (Template:IPAc-en) (Nobiin: Nobī;<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Template:Langx) are a Nilo-Saharan speaking ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of the earliest cradles of civilization.<ref>Charles Keith Maisels (1993). The Near East: Archaeology in the "Cradle of Civilization. Routledge. Template:ISBN.</ref> In the southern valley of Egypt, Nubians differ culturally and ethnically from Egyptians, although they intermarried with them and other ethnic groups, especially Arabs.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> They speak Nubian languages as a mother tongue, part of the Northern Eastern Sudanic languages, and Arabic as a second language.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Neolithic settlements have been found in the central Nubian region dating back to 7000 BC, with Wadi Halfa believed to be the oldest settlement in the central Nile valley.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Parts of Nubia, particularly Lower Nubia, were at times a part of ancient Pharaonic Egypt and at other times a rival state representing parts of Meroë or the Kingdom of Kush. By the Twenty-fifth Dynasty (744 BC–656 BC), all of Egypt was united with Nubia, extending down to what is now Khartoum.<ref name="britannica.com">Template:Cite web</ref> However, in 656 BC, the native Twenty-sixth Dynasty regained control of Egypt. As warriors, the ancient Nubians were famous for their skill and precision with the bow and arrow.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> In the Middle Ages, the Nubians converted to Christianity and established three kingdoms: Nobatia in the north, Makuria in the center, and Alodia in the south. They then converted to Islam during the Islamization of the Sudan region.

Today, Nubians in Egypt primarily live in southern Egypt, especially in Kom Ombo and Nasr al-Nuba (Template:Langx) north of Aswan,<ref name=20161025egypttoday>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and large cities such as Cairo, while Sudanese Nubians live in northern Sudan, particularly in the region between the city of Wadi Halfa on the Egypt–Sudan border and al Dabbah. Some Nubians were forcibly moved to Khashm el Girba and New Halfa upon the construction of the High Dam in Egypt which flooded their ancestral lands. Additionally, a group known as the Midob live in northern Darfur, a group named Birgid in Central Darfur and several groups known as the Hill Nubians who live in Northern Kordofan in Haraza and a few villages in the northern Nuba Mountains in South Kordofan state.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

The main Nile Nubian groups from north to south are the Kenzi (Kenzi/Mattokki-speaking), Faddicca (Nobiin-speaking), Halfawi (Nobiin-speaking), Sukkot (Nobiin-speaking), Mahas (Nobiin-speaking), and Danagla (Andaandi-speaking).<ref name="Lobban">Template:Cite book</ref>

Etymology

Throughout history various parts of Nubia were known by different names, including Template:Langx "Land of the Bow", tꜣ nḥsj, jꜣm "Kerma", jrṯt, sṯjw, wꜣwꜣt, Meroitic: akin(e) "Lower "Nubia", and Greek Aethiopia.<ref name="oi.uchicago.edu"/> The origin of the names Nubia and Nubian is contested. Based on cultural traits, some scholars believe Nubia is derived from the Template:Langx "gold",<ref name="Bianchi">Template:Cite book</ref> although there is no such usage of the term as an ethnonym or toponym that can be found in known Egyptian texts; the Egyptians referred to people from this area as the nḥsj.w. The Roman Empire used the term "Nubia" to describe the area of Upper Egypt and northern Sudan.<ref name="oi.uchicago.edu">Template:Cite web</ref>

History

The prehistory of Nubia dates to the Paleolithic around 300,000 years ago. By about 6000 BC, peoples in the region had developed an agricultural economy. In their history,Template:When they adopted the Egyptian hieroglyphic system. Ancient history in Nubia is categorized according to the following periods:<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> A-Group culture (3700–2800 BC), C-Group culture (2300–1600 BC), Kerma culture (2500–1500 BC), Nubian contemporaries of the New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC), the Twenty-fifth Dynasty (1000–653 BC), Napata (1000–275 BC), Meroë (275 BC–300/350 AD), Makuria (340–1317 AD), Nobatia (350–650 AD), and Alodia (600s–1504 AD).

Archaeological evidence has attested that population settlements occurred in Nubia as early as the Late Pleistocene era and from the 5th millennium BC onwards, whereas there is "no or scanty evidence" of human presence in the Egyptian Nile Valley during these periods, which may be due to problems in site preservation.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Several scholars have argued that the African origins of the Egyptian civilisation derived from pastoral communities which emerged in both the Egyptian and Sudanese regions of the Nile Valley in the fifth millennium BCE.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Various biological anthropological studies have shown close, biological affinities between the predynastic southern, Egyptian and the early Nubian populations.<ref>"When Mahalanobis D2 was used,the Naqadan and Badarian Predynastic samples exhibited more similarity to Nubian, Tigrean, and some more southern series than to some mid- to late Dynasticseries from northern Egypt (Mukherjee et al., 1955). The Badarian have been found to be very similar to a Kerma sample (Kushite Sudanese), using both the Penrose statistic (Nutter, 1958) and DFA of males alone (Keita,1990). Furthermore, Keita considered that Badarian males had a southern modal phenotype, and that together with a Naqada sample, they formed a southern Egyptian cluster as tropical variants together with a sample from Kerma". Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>"Keita (1992), using craniometrics, discovered that the Badarian series is distinctly different from the later Egyptian series, a conclusion that is mostly confirmed here. In the current analysis, the Badari sample more closely clusters with the Naqada sample and the Kerma sample". Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Frank Yurco (1996) remarked that depictions of pharonic iconography such as the royal crowns, Horus falcons and victory scenes were concentrated in the Upper Egyptian Naqada culture and A-Group Lower Nubia. He further elaborated that "Egyptian writing arose in Naqadan Upper Egypt and A-Group Lower Nubia, and not in the Delta cultures, where the direct Western Asian contact was made, [which] further vitiates the Mesopotamian-influence argument".<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

In 2023, Christopher Ehret reported that the existing archaeological, linguistic, biological anthropological and genetic evidence had determined the founding populations of Ancient Egyptian areas such as Naqada and El-Badari to be the descendants of longtime inhabitants in Northeastern Africa which included Egypt, Nubia and the northern Horn of Africa.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

The linguistic affinities of early Nubian cultures are uncertain. Some research has suggested that the early inhabitants of the Nubia region, during the C-Group and Kerma cultures, were speakers of languages belonging to the Berber and Cushitic branches, respectively, of the Afroasiatic family. More recent research instead suggests that the people of the Kerma culture spoke Nilo-Saharan languages of the Eastern Sudanic branch and that the peoples of the C-Group culture to their north spoke Cushitic languages.<ref name="Rilly2010">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="Rilly200162">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Rilly2008">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="Cooper">Template:Cite journal</ref> They were succeeded by the first Nubian language speakers, whose tongues belonged to another branch of Eastern Sudanic languages within the Nilo-Saharan phylum.<ref name="Bechhaus-Gerst"/><ref name="Lbant"/> A 4th-century AD victory stela commemorative of Axumite king Ezana contains inscriptions describing two distinct population groups dwelling in ancient Nubia: a "red" population and a "black" population.<ref name="Ezanastel">Template:Cite book</ref>

Although Egypt and Nubia have a shared pre-dynastic and pharaonic history, the two histories diverge with the fall of Ancient Egypt and the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great in 332 BC.<ref name="britannica.com"/> At this point, the area of land between the 1st and the 6th cataract of the Nile became known as Nubia.

Egypt was conquered first by the Persians and named the Satrapy (Province) of Mudriya, and two centuries later by the Greeks and then the Romans. During the latter period, however, the Kushites formed the kingdom of Meroë, which was ruled by a series of Candaces or Queens. The Candace of Meroë was able to intimidate Alexander the Great into retreat with a great army of elephants, while historical documents suggest that the Nubians defeated the Roman Emperor Augustus Caesar, resulting in a favorable peace treaty for Meroë.<ref>Template:Cite encyclopedia</ref> The kingdom of Meroë also defeated the Persians, and later Christian Nubia defeated the invading Arab armies on three different occasions resulting in the 600 year peace treaty of Baqt, the longest lasting treaty in history.<ref>Jakobielski, S. 1992. Chapter 8: "Christian Nubia at the Height of its Civilization." UNESCO General History of Africa, Volume III. University of California Press</ref> The fall of the kingdom of Christian Nubia occurred in the early 1500s resulting in full Islamization and reunification with Egypt under the Ottoman Empire, the Muhammad Ali dynasty, and British colonial rule. After the 1956 independence of Sudan from Egypt, Nubia and the Nubian people became divided between Southern Egypt and Northern Sudan.

Modern Nubians speak Nubian languages, Eastern Sudanic languages that is part of the Nilo-Saharan family. The Old Nubian language is attested from the 8th century AD, and may be the oldest well-recorded language of Africa outside of the Afroasiatic family, depending on the classification of Meroitic and the language of the Garamantes.

Nubia consisted of four regions with varied agriculture and landscapes. The Nile river and its valley were found in the north and central parts of Nubia, allowing farming using irrigation. The western Sudan had a mixture of peasant agriculture and nomadism. Eastern Sudan had primarily nomadism, with a few areas of irrigation and agriculture. Finally, there was the fertile pastoral region of the south, where Nubia's larger agricultural communities were located.<ref name="Lobban 2004 liii">Template:Cite book</ref>

Nubia was dominated by kings from clans that controlled the gold mines. Trade in exotic goods from other parts of Africa (ivory, animal skins) passed to Egypt through Nubia.

Language

Modern Nubians speak Nubian languages. They belong to the Eastern Sudanic branch of the Nilo-Saharan phylum. But there is some uncertainty regarding the classification of the languages spoken in Nubia in antiquity. There is some evidence that Cushitic languages were spoken in parts of Lower (northern) Nubia, an ancient region which straddles present-day Southern Egypt and Northern Sudan, and that Eastern Sudanic languages were spoken in Upper and Central Nubia, before the spread of Eastern Sudanic languages even further north into Lower Nubia.<ref name="Cooper" />

Peter Behrens (1981) and Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst (2000) suggest that the ancient peoples of the C-Group and Kerma civilizations spoke Afroasiatic languages of the Berber and Cushitic branches, respectively.<ref name="Bechhaus-Gerst">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="Lbant">Template:Cite book</ref> They propose that the Nilo-Saharan Nobiin language today contains a number of key pastoralism related loanwords that are of Berber or proto-Highland East Cushitic origin, including the terms for sheep/goatskin, hen/cock, livestock enclosure, butter and milk. This in turn, is interpreted to suggest that the C-Group and Kerma populations, who inhabited the Nile Valley immediately before the arrival of the first Nubian speakers, spoke Afroasiatic languages.<ref name="Bechhaus-Gerst"/>

Claude Rilly (2010, 2016) and Julien Cooper (2017) on the other hand, suggest that the Kerma peoples (of Upper Nubia) spoke Nilo-Saharan languages of the Eastern Sudanic branch, possibly ancestral to the later Meroitic language, which Rilly also suggests was Nilo-Saharan.<ref name="Rilly2010" /><ref name="Rilly200162"/> Rilly also considers evidence of significant early Afro-Asiatic influence, especially Berber, on Nobiin to be weak (and where present, more likely due to borrowed loanwords than substrata), and considers evidence of substratal influence on Nobiin from an earlier now extinct Eastern Sudanic language to be stronger.<ref name="Rilly2008"/> Julien Cooper (2017) suggests that Nilo-Saharan languages of the Eastern Sudan branch were spoken by the people of Kerma, those further south along the Nile, to the west, and those of Saï (an island to the north of Kerma), but that Afro-Asiatic (most likely Cushitic) languages were spoken by other peoples in Lower Nubia (such as the Medjay and the C-Group culture) living in Nubian regions north of Saï toward Egypt and those southeast of the Nile in Punt in the Eastern dessert. Based partly on an analysis of the phonology of place names and personal names from the relevant regions preserved in ancient texts, he argues that the terms from "Kush" and "Irem" (ancient names for Kerma and the region south of it respectively) in Egyptian texts display traits typical of Eastern Sudanic languages, while those from further north (in Lower Nubia) and east are more typical of the Afro-Asiatic family, noting: "The Irem-list also provides a similar inventory to Kush, placing this firmly in an Eastern Sudanic zone. These Irem/Kush-lists are distinctive from the Wawat-, Medjay-, Punt-, and Wetenet-lists, which provide sounds typical to Afroasiatic languages."<ref name="Cooper" />

It is also uncertain to which language family the ancient Meroitic language is related. Kirsty Rowan suggests that Meroitic, like the Egyptian language, belongs to the Afroasiatic family. She bases this on its sound inventory and phonotactics, which, she argues, are similar to those of the Afroasiatic languages and dissimilar from those of the Nilo-Saharan languages.<ref>Rowan, Kirsty (2011). "Meroitic Consonant and Vowel Patterning". Lingua Aegytia, 19.</ref><ref>Rowan, Kirsty (2006), "Meroitic – An Afroasiatic Language?" Template:Webarchive Template:Abbr Working Papers in Linguistics 14:169–206.</ref> Claude Rilly proposes, based on its syntax, morphology, and known vocabulary, that Meroitic, like the Nobiin language, belongs to the Eastern Sudanic branch of the Nilo-Saharan family.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Nubian Greeks

The Noba conquest of Kush and the Axumite capture of Meroe

The Kingdom of Kush persisted as a major regional power until the fourth century AD, when it weakened and disintegrated amid worsening climatic conditions, internal rebellions, and foreign invasions— notably by the Noba people, who introduced the Nubian languages and gave their name to Nubia itself. While the Kushites were occupied by war with the Noba and the Blemmyes, the Aksumites took the opportunity to capture Meroë and loot its gold. Negus Ezana then took on the title of "King of Ethiopia,"<ref>Munro-Hay, Stuart (1991). Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0748601066</ref> a practice which would last into the modern period and was recorded in inscriptions found in both Axum and Meroe. Although the Aksumite presence was likely short-lived, it prompted the dissolution of the Kushite kingdom into the three polities of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia. The Kingdom of Alodia subsequently gained control of the southern territory of the former Meroitic empire, including parts of Eritrea.<ref>Derek Welsby (2014): "The Kingdom of Alwa" in "The Fourth Cataract and Beyond". Peeters.</ref> The Axumite Empire of Ethiopia engaged in a series of invasions that culminated in the capture of the Nubian capital of Meroë in the middle of the 4th century AD, signaling the end of independent Nubian Pagan kingdoms. The Axumites then sent missionaries to Nubia to establish similar Syrian-based Christianity like in Ethiopia, but were competing with Egyptian-based Christianity, who eventually established the authority of the Coptic Church in the area, and founded new Nubian Christian kingdoms, such as Nobatia, Alodia, and Makuria.<ref name="mohammadali">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="mhonegger">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="christianityaswannubia">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="garthfowden">Template:Cite book</ref>

Tribal nomads like the Beja, Afar, and Saho managed to remain autonomous due to their uncentralized nomadic nature. These tribal peoples would sporadically inflict attacks and raids on Axumite communities. The Beja nomads eventually Hellenized and integrated into the Nubian Greek society that had already been present in Lower Nubia for three centuries.<ref name="mohammadali" /><ref name="mhonegger" /><ref name="christianityaswannubia" />

Nubian Greek society

Nubian Greek culture followed the pattern of Egyptian Greek and Byzantine Greek civilization, expressed in Nubian Greek art and Nubian Greek literature. The earliest attestations of Nubian Greek literature come from the 5th century; the Nubian Greek language resembles Egyptian and Byzantine Greek; it served as a lingua franca throughout the Nubian Kingdoms, and had a creolized form for trade among the different peoples in Nubia.<ref name="ghrhorsley">Template:Cite book</ref>

Nubian Greek was unique in that it adopted many words from both Coptic Egyptian and Nubian; Nubian Greek's syntax also evolved to establish a fixed word order.<ref name="oxfordancientnubia">Template:Cite book</ref>

The following is an example of Nubian Greek language:

Template:Blockquote Template:Blockquote Template:Blockquote

A plethora of frescoes created between 800–1200Template:NbspAD in Nubian cities such as Faras depicted religious life in the courts of the Nubian Kingdoms; they were made in Byzantine art style.<ref name="whcfrend">Template:Cite book</ref>

Nubian Greek titles and government styles in Nubian Kingdoms were based on Byzantine models; even with Islamic encroachments and influence into Nubian territory, the Nubian Greeks saw Constantinople as their spiritual home.<ref name="whcfrend" /> Nubian Greek culture disappeared after the Muslim conquest of Nubia around 1450Template:NbspAD.<ref name="whcfrend" />

Modern Nubians

The descendants of the ancient Nubians still inhabit the general area of what was ancient Nubia. They currently live in what is called Old Nubia, mainly located in modern Egypt and Sudan. Nubians have been resettled in large numbers (an estimated 50,000 people) away from Wadi Halfa North Sudan in to Khashm el Girba – Sudan and some moved to Southern Egypt since the 1960s, when the Aswan High Dam was built on the Nile, flooding ancestral lands.<ref name="Fernea 2005 ix-xi">Template:Cite book</ref> Most Nubians nowadays work in Egyptian and Sudanese cities. Whereas Arabic was once only learned by Nubian men who travelled for work, it is increasingly being learned by Nubian women who have access to school, radio and television. Nubian women are working outside the home in increasing numbers.<ref name="Fernea 2005 ix-xi"/>

During the Yom Kippur War of 1973, Egypt employed Nubian people as Code talkers.<ref name=20140201nationalgeographic>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

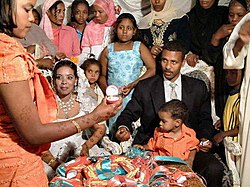

Culture

Nubians have developed a common identity, which has been celebrated in poetry, novels, music, and storytelling.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Nubians in modern Sudan include the Danagla around Dongola Reach, the Mahas from the Third Cataract to Wadi Halfa, and the Sikurta around Aswan. These Nubians write using their own script. They also practice scarification: Mahas men and women have three scars on each cheek, while the Danaqla wear these scars on their temples. Younger generations appear to be abandoning this custom.<ref name="Clammer 2010 138">Template:Cite book</ref>

Nubia's ancient cultural development was influenced by its geography. It is sometimes divided into Upper Nubia and Lower Nubia. Upper Nubia was where the ancient Kingdom of Napata (the Kush) was located. Lower Nubia has been called "the corridor to Africa", where there was contact and cultural exchange between Nubians, Egyptians, Greeks, Assyrians, Romans, and Arabs. Lower Nubia was also where the Kingdom of Meroe flourished.<ref name="Lobban 2004 liii"/> The languages spoken by modern Nubians are based on ancient Sudanic dialects. From north to south, they are: Kenuz, Fadicha (Matoki), Sukkot, Mahas, Danagla.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Kerma, Nepata, and Meroe were Nubia's largest population centres. The rich agricultural lands of Nubia supported these cities. Ancient Egyptian rulers sought control of Nubia's wealth, including gold, and the important trade routes within its territories.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Nubia's trade links with Egypt led to Egypt's domination over Nubia during the New Kingdom period. The emergence of the Kingdom of Meroe in the 8th century BC led to Egypt being under the control of Nubian rulers for a century, although they preserved many Egyptian cultural traditions.<ref name="Bulliet, Richard W., and Pamela Kyle Crossley, Daniel R. Headrick, Lyman L. Johnson, Steven W. Hirsch 2007 83">Template:Cite book</ref> Nubian kings were considered pious scholars and patrons of the arts, copying ancient Egyptian texts and even restoring some Egyptian cultural practices.<ref name="Remier 2010 135">Template:Cite book</ref> After this, Egypt's influence declined greatly. Meroe became the centre of power for Nubia and cultural links with other parts of Africa gained greater influence.<ref name="Bulliet, Richard W., and Pamela Kyle Crossley, Daniel R. Headrick, Lyman L. Johnson, Steven W. Hirsch 2007 83"/>

Religion

Today, Nubians practice Islam. To a certain degree, Nubian religious practices involve a syncretism of Islam and traditional folk beliefs.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> In ancient times, Nubians practiced a mixture of traditional religion and Egyptian religion. Prior to the spread of Islam, many Nubians practiced Christianity.<ref name="Clammer 2010 138"/>

Beginning in the eighth century, Islam arrived in Nubia. Though Christians and Muslims (primarily Arab merchants at this period) may have lived peacefully together, Arab armies often invaded Christian Nubian kingdoms. An example of this being Makuria, where in 651 an Arab army invaded, but was repulsed, and a treaty known as the Baqt was signed, preventing further Arab invasions in exchange for 360 slaves each year. Notably, the Baqt required Nubians to maintain a mosque for Muslim visitors and residents. This, and with the following Ottoman occupation of Lower Nubia in the 1560s, led to the kingdom and Christian Nubian society to disappear. The former Makurian territories south of the 3rd cataract, including the former capital Dongola, had been annexed by the Islamic Funj Sultanate by the early 16th century.<ref>Manning, P. (1990). Slavery and African life: occidental, oriental, and African slave trades. Storbritannien: Cambridge University Press. p. 28-29</ref> Over time, the Nubians gradually converted to Islam, beginning with the Nubian elite. Islam was mainly spread via Sufi preachers that settled in Nubia in the late 14th century onwards.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> By the sixteenth century, most of the Nubians were Muslim.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Ancient Nepata was an important religious centre in Nubia. It was the location of Gebel Barkal, a massive sandstone hill resembling a rearing cobra in the eyes of the ancient inhabitants. Egyptian priests declared it to be the home of the ancient deity Amun, further enhancing Nepata as an ancient religious site. This was the case for both Egyptians and Nubians. Egyptian and Nubian deities alike were worshipped in Nubia for 2,500 years, even while Nubia was under the control of the New Kingdom of Egypt.<ref name="Remier 2010 135"/> Nubian kings and queens were buried near Gebel Barkal, in pyramids as the Egyptian pharaohs were. Nubian pyramids were built at Gebel Barkal, at Nuri (across the Nile from Gebel Barkal), at El Kerru, and at Meroe, south of Gebel Barkal.<ref name="Remier 2010 135"/>

Architecture

Modern Nubian architecture in Sudan is distinctive, and typically features a large courtyard surrounded by a high wall. A large, ornately decorated gate, preferably facing the Nile, dominates the property. Brightly colored stucco is often decorated with symbols connected with the family inside, or popular motifs such as geometric patterns, palm trees, or the evil eye that wards away bad luck.<ref name="Clammer 2010 138"/>

Nubians invented the Nubian vault, a type of curved surface forming a vaulted structure.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Genetics

Autosomal DNA has been extensively studied in recent years, and some of the findings are as follows:

- Babiker, H. M., Schlebusch, C. M., Hassan, H. Y., et al. (2011) revealed that individuals from northern Sudan clustered with those from Egypt, while individuals from South Sudan clustered with those from Karamoja (Uganda). They conclude that "the similarity of the Nubian and Egyptian populations suggest that migration, potentially bidirectional, occurred along the Nile river Valley, which is consistent with the historical evidence for long-term interactions between Egypt and Nubia.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Dobon et al. (2015) identified an ancestral autosomal component of West Eurasian origin that is common to many Sudanese Arabs, Nubians and Afroasiatic-speaking populations in the region. Nubians were found to be genetically modelled similar to their Cushitic and Semitic (Afro-Asiatic) neighbors (such as the Beja, Sudanese Arabs, and Ethiopians) rather than to other Nilo-Saharan speakers who lack this Middle Eastern/North African influence. The study showed that these populations formed a "North-East cluster", which included Northern Sudanese. This may be explained by the aforementioned groups being a mixture of a population similar to Modern Coptic Egyptians, and an ancestral Southern African one.<ref name="Dobon2015">Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Sirak et al. (2015) analysed the DNA of a Christian-period inhabitant of Kulubnarti in northern Nubia near the Egyptian border. They found that this individual was most closely related to Middle Eastern populations.<ref name=researchgate275031861>Template:Cite web</ref> Further excavations of two Early Christian period (AD 550–800) cemeteries at Kulubnarti, one located on the mainland and the other on an island, revealed the existence of two ancestrally and socioeconomically distinct local populations. Preliminary results, including mitochondrial haplogroup analysis, suggests there may be substantial differences in the genetic composition between the two communities, with 70% of individuals from the island cemetery demonstrating African-based haplogroups (L2, L1, and L5), compared to only 36.4% of mainlanders, who instead show an increased prevalence of European and Near Eastern haplogroups (including K1, H, I5, and U1).<ref name="Sirak2016">Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Hollfelder et al. (2017) analysed various populations in Sudan and observed close autosomal affinities between their Nubian and Sudanese Arab samples. The authors concluded that the "Nubians can be seen as a group with substantial genetic material relating to Nilotes that later received much gene-flow from Eurasians and East Africans. The strongest admixture came from Eurasian populations and was likely quite extensive: 39.41%–47.73%." The study also showed "almost no West African component or, at a higher K, Bantu component".<ref name="Hollfelder">Template:Cite journal</ref>

- In 2018, Carina M. Schlebusch and Mattias Jakobsson in the Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, found that Nilotic populations from South Sudan (e.g. Dinka, Nuer and Shilluk) remained isolated and received little to no geneflow from Eurasians, West African Bantu-speaking farmers, and other surrounding groups. In contrast, Nubians and Arabs in the north showed admixture from Western Eurasian populations. The population structure analysis and inferred ancestry showed that "the Nubian, Arab, and Beja populations of northeastern Africa roughly display equal admixture fractions from a local northeastern African gene pool (similar to the Nilotic component) and an incoming Eurasian migrant component."<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Bird, Nancy et al. (2023) discovered that, in contrast to other African groups which saw strong correlation between genetics, ethnicity and geography, the genetic patterns of variation among Sudanese Arabs, Nubians, and Beja, showed no correspondence with ethnicity. All these communities had individuals who fell into two main clusters: Sudan Nile 1 and Sudan Nile 2, with the first showing a maximum of 12% inferred Arabian-related ancestry, and the second upwards of 48%. The main difference between the pooled clusters was the proportion of the component related to Saudi Arabia, with less of such ancestry more commonly seen in the Nubians and Beja on average.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Y-DNA

A 2003 study by Lucotte and Mercier<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> analyzed Y-chromosome haplogroups among 274 unrelated males in Egypt. Included in the study were Lower Nubian populations from Abu Simbel, with the individuals originating from this locality self-identified as Nubians. The research focused on using the p49a,f/TaqI haplotype polymorphisms, which can be linked to modern phylogenetic classifications. Samples from these 46 Nubians revealed the following Y-Chromosome Haplogroups (genetic composition):

- E1b1b (E-M35): 86.9% of the population, represented by three haplotypes: - Haplotype IV: 39.1% - Haplotype V: 17.4% - Haplotype XI: 30.4%

- J1 (Haplotype VII): 2.2%

- J2 (Haplotype VII): 2.2%

- Other lineages were XIII at 2.2%, III at 4.3% and XVI at 2.2%

In 2008 results of an analysis by Hisham Y. Hassan of modern Sudanese entitled Chromosome Variation Among Sudanese: Restricted Gene Flow, Concordance With Language, Geography, and History<ref name="Hassan 2008">Hassan, Hisham Y. et al. 2008 Template:Citation</ref> included 39 Nubians found to be of the following Y Chromosome Haplogroups:

- J1 41%

- J2 2%

- E3b1 (E-M78) 15.3%

- E3 (E-M215) 7.6%

- R1b 10.3%

- B-M60 7.7%

- F 10.2%

- I 5.1%

Christian-Era DNA

Sirak et al. (2021) obtained and analyzed the whole genomes of 66 individuals from the site of Kulubnarti situated between the 2nd and 3rd cataract and dated to the Christian period between 650 and 1000 CE. The samples were obtained from two cemeteries, R and S. Grave materials between the two cemeteries did not differ, but physical analyses of the remains found differences in morbidity and mortality indicating that the R cemetery individuals were of a higher social class than the cemetery S individuals. The study analyzed the data they obtained along with other published ancient and modern samples from Africa and West Eurasia. The genetic profile of the sampled Christian-era Nubians was found to be a mixture between West Eurasian and Sub Saharan Dinka-related ancestries. The samples were estimated to have approximately 60% West Eurasian related ancestry that likely came from ancient Egyptians but ultimately resembles that found in Bronze or Iron Age Levantines. They also carried approximately 40% Dinka-related ancestry. The study commented that the results reflect deep biological connections among the populations of the Nile Valley and further confirm the presence of West Eurasian ancestry in the Nile valley prior to Arab migrations.

The two cemeteries showed minimal differences in their West Eurasian/Dinka ancestry proportions, formed a genetic clade with each other in relation to other populations, and had a small FST value of 0.0013 reflecting a small genetic distance. These findings in addition to multiple cross cemetery relatives that the analyses have revealed indicate that people of both the R and S cemeteries were part of the same population despite the archaeological and anthropological differences between the two burials showing social stratification.

The study found some difference in Y haplogroups profiles between the two cemeteries with the S cemetery having more west Asian clades. the difference was found to be insignificant, and the study viewed it as likely to be a statistical fluctuation and not evidence of heterogeneity among males from the two cemeteries.

Regarding modern Nubians in Sudan, despite their superficial resemblance to the Kulubnarti Nubians on the PCA, they were not found to be descended directly from Kulubnarti Nubians without additional admixture following the Christian period.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Notable Nubians

- Luqman, Ancient wise man in Islamic tradition

- Alara of Kush, founder of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt

- Mentuhotep II (possibly), the sixth ruler of the Eleventh Dynasty. United Egypt and established the Middle Kingdom of Egypt

- Amenemhat I, founder of the Twelfth Dynasty. Many scholars in recent years have argued that his mother was of Nubian descent.

- Taharqa, Pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty.

- Amanitore, Kandake (queen) of the Kingdom of Kush centered on Meroë

- Silko, 6th-century king of the Noubades and all of the Ethiopians, associated with the Christianization of Nubia

- Qalidurut, 7th-century king of Makuria, defeated the Arab Muslim invasion at the First Battle of Dongola and Second Battle of Dongola, signed the Baqt

- Merkourios, 8th-century king of Dotawo, unifier of Nobatia and Makuria, referred to as the New Constantine by John the Deacon

- Kyriakos of Makuria, 8th-century king of Makuria. Invaded Egypt to rescue Pope Michael I of Alexandria

- Rafael of Makuria, 10th-century Nubian king of Makuria. Built the famous " Red Palace" at Dongola

- Salomo of Makuria, 11th-century king of Dotawo. United the kingdom of Dongola and Soba

- Moses Georgios of Makuria, 12th-century "king of Alodia, Makuria, Nobadia, Dalmatia[g] and Axioma", mostly known for his conflict with Ayyubids

- Georgios I of Makuria, king of Makuria, son of Zacharias III Renegotiated the Baqt with the Abassids

- Jaafar an-Nimeiry, former Sudanese president

- Khalil Farah, 20th-century Sudanese Nubian musician.

- Mohamed Mounir, Egyptian Nubian Singer, known as "The King"

- Mohammed Wardi, Sudanese Nubian singer

- Mo Ibrahim, Sudanese-British mobile communications entrepreneur and billionaire

- Hamza El Din, singer and musicologist

- Khalil Kalfat, literary critic, political and economic thinker and writer

- Abdallah Khalil, ex-Sudanese prime minister, co-founder of the White Flag League, co-founder and ex-general secretary of the Umma Party

- Mohamed Hussein Tantawi Soliman, Egyptian Field Marshal and statesman, commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Armed Forces, de facto head of state of Egypt

- Muhammad Ahmad, 19th-century Sufi sheikh and revolutionary leader of the Ansar

- Jamal Mohammed Ahmed, Sudanese writer, historian, and diplomat

- Osama Abdul Latif, a Sudanese businessman, chairman of DAL Group

- Idris Ali, Egyptian novelist and short story writer

- Fathi Hassan, painter

- Ali Ghazal, Egyptian footballer

- Ali Hassan Kuban, singer

- Taha Abdelmagid

- Abdel Raouf

- Amjad Ismail

- Haitham Mustafa

- Mazin Mohamedein

- Musab Ahmed

- Mohamed Homos

See also

- Barabra is an old ethnographical term for the Nubian peoples of Sudan and southern Egypt.

- Nubian wig worn by the affluent society of ancient Egypt

- Aethiopia is an ancient Greek geographical term which referred to the regions of Sudan and areas south of the Sahara desert.

Notes

References

Citations

General references

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Black Pharaohs - National Geographic Feb 2008

External links

- Template:Usurped

- Nubian people history

- Johanna Granville "Nubians of Egypt and Sudan Past and Present"

- Nubians Template:Webarchive by Abubakr Sidahmed

- Nubians Use Hip-hop to Preserve Culture – Sudan Tribune Template:Webarchive

- "The Forgotten Minorities: Egypt's Nubians and Amazigh in the Amended Constitution"