Creatine

Template:Short description Template:Distinguish Template:Pp-pc Template:Use dmy dates Template:Chembox

Creatine (Template:IPAc-en or Template:IPAc-en)<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> is an organic compound that, in vertebrates, facilitates recycling of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), primarily in muscle and brain tissue. Its phosphorylated form, phosphocreatine, donates phosphate groups to adenosine diphosphate (ADP), turning it back into ATP. Creatine also acts as a buffer.<ref name="pmid26202197">Template:Cite journal</ref> It has the nominal formula Template:Chem2 and in solutions, exists in various tautomers, including a neutral form and zwitterionic forms.

History

Creatine was first identified in 1832 when Michel Eugène Chevreul isolated it from the basified water-extract of skeletal muscle. He later named the crystallized precipitate after the Greek word for meat, Template:Lang (Template:Lang). In 1928, creatine was shown to exist in equilibrium with creatinine.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Studies in the 1920s showed that consumption of large amounts of creatine did not result in its excretion. This result pointed to the ability of the body to store creatine, which in turn suggested its use as a dietary supplement.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

In 1912, Harvard University researchers Otto Folin and Willey Glover Denis found evidence that ingesting creatine can dramatically boost the creatine content of the muscle.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The discovery of phosphocreatine was reported in 1927.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

In the 1960s, the enzyme creatine kinase (CK) was shown to phosphorylate ADP using phosphocreatine (PCr) to generate ATP. It follows that ATP - not PCr - is directly consumed in muscle contraction. CK uses creatine to buffer the ATP/ADP ratio.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

While creatine's influence on physical performance has been well documented since the early twentieth century, it came into public view following the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. An August 7, 1992 article in The Times reported that Linford Christie, the gold medal winner at 100 meters, had used creatine before the Olympics (however, it should also be noted that Christie was found guilty of doping later in his career).<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> An article in Bodybuilding Monthly named Sally Gunnell, who was the gold medalist in the 400-meter hurdles, as another creatine user. In addition, The Times also noted that 100 meter hurdler Colin Jackson began taking creatine before the Olympics.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

At the time, low-potency creatine supplements were available in Britain, but creatine supplements designed for strength enhancement were not commercially available until 1993 when a company called Experimental and Applied Sciences (EAS) introduced the compound to the sports nutrition market under the name Phosphagen.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> In 1996, researchers found that carbohydrate consumption augments the effects of creatine supplementation on skeletal muscle creatine accumulation.<ref name=":4">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Metabolic role

Creatine is a naturally occurring non-protein compound and the primary constituent of phosphocreatine, which is used to regenerate ATP within the cell. 95% of the human body's total creatine and phosphocreatine stores are found in skeletal muscle, while the remainder is distributed in the blood, brain, testes, and other tissues.<ref name="pmid22817979">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pmid26874700">Template:Cite journal</ref> The typical creatine content of skeletal muscle (as both creatine and phosphocreatine) is 120 mmol per kilogram of dry muscle mass, but can reach up to 160 mmol/kg through supplementation.<ref name=":2">Template:Cite journal</ref> Approximately 1–2% of intramuscular creatine is degraded per day and an individual would need about 1–3 grams of creatine per day to maintain average (unsupplemented) creatine storage.<ref name=":2" /><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name=":5">Template:Cite journal</ref> An omnivorous diet provides roughly half of this value, with the remainder synthesized in the liver and kidneys.<ref name="pmid22817979" /><ref name="pmid26874700" /><ref name="pmid21387089">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Biosynthesis

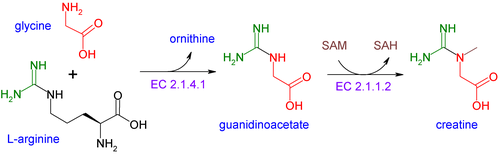

Creatine is not an essential nutrient.<ref name="Creatine">Template:Cite web</ref> It is an amino acid derivative, naturally produced in the human body from the amino acids glycine and arginine, with an additional requirement for S-adenosyl methionine (a derivative of methionine) to catalyze the transformation of guanidinoacetate to creatine. In the first step of the biosynthesis, the enzyme arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT, EC:2.1.4.1) mediates the reaction of glycine and arginine to form guanidinoacetate. This product is then methylated by guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase (GAMT, EC:2.1.1.2), using S-adenosyl methionine as the methyl donor. Creatine itself can be phosphorylated by creatine kinase to form phosphocreatine, which is used as an energy buffer in skeletal muscles and the brain. A cyclic form of creatine, called creatinine, exists in equilibrium with its tautomer and with creatine.

Phosphocreatine system

Creatine is transported through the blood and taken up by tissues with high energy demands, such as the brain and skeletal muscle, through an active transport system. The concentration of ATP in skeletal muscle is usually 2–5 mM, which would result in a muscle contraction of only a few seconds.<ref name="ncbi.nlm.nih.gov">Template:Cite journal</ref> During times of increased energy demands, the phosphagen (or ATP/PCr) system rapidly resynthesizes ATP from ADP with the use of phosphocreatine (PCr) through a reversible reaction catalysed by the enzyme creatine kinase (CK). The phosphate group is attached to an NH center of the creatine. In skeletal muscle, PCr concentrations may reach 20–35 mM or more. Additionally, in most muscles, the ATP regeneration capacity of CK is very high and is therefore not a limiting factor. Although the cellular concentrations of ATP are small, changes are difficult to detect because ATP is continuously and efficiently replenished from the large pools of PCr and CK.<ref name="ncbi.nlm.nih.gov" /> Creatine has the ability to increase muscle stores of PCr, potentially increasing the muscle's ability to resynthesize ATP from ADP to meet increased energy demands.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal.</ref><ref>T. Wallimann, M. Tokarska-Schlattner, D. Neumann u. a.: The Phosphocreatine Circuit: Molecular and Cellular Physiology of Creatine Kinases, Sensitivity to Free Radicals, and Enhancement by Creatine Supplementation. In: Molecular System Bioenergetics: Energy for Life. 22. November 2007. Template:DoiC</ref>

Creatine supplementation appears to increase the number of myonuclei that satellite cells will donate to damaged muscle fibers, which increases the potential for growth of those fibers. This increase in myonuclei probably stems from creatine's ability to increase levels of the myogenic transcription factor MRF4.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Genetic deficiencies

Template:Main Genetic defects in the creatine biosynthetic pathway enzymes lead to various severe neurological defects.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Defects in the two synthesis enzymes cause L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase deficiency and guanidinoacetate methyltransferase deficiency. Both biosynthetic defects are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Creatine transporter defect, characterized by insufficient transport of creatine to the brain, is caused by mutations in SLC6A8 and is inherited in an X-linked manner.<ref name="creatinedefects">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Vegans and vegetarians

Vegan and vegetarian diets are associated with lower levels of muscle creatine, and athletes on these diets may benefit from creatine supplementation.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Pharmacokinetics

Most of the research to-date on creatine has predominantly focused on the pharmacological properties of creatine, yet there is a lack of research into the pharmacokinetics of creatine. Studies have not established pharmacokinetic parameters for clinical usage of creatine such as volume of distribution, clearance, bioavailability, mean residence time, absorption rate, and half life. A clear pharmacokinetic profile would need to be established prior to optimal clinical dosing.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Dosing

Loading phase

An approximation of 0.3 g/kg/day divided into 4 equal spaced intervals has been suggested since creatine needs may vary based on body weight.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":2" /> It has also been shown that taking a lower dose of 3 grams a day for 28 days can also increase total muscle creatine storage to the same amount as the rapid loading dose of 20 g/day for 6 days.<ref name=":2" /> However, a 28-day loading phase does not allow for ergogenic benefits of creatine supplementation to be realized until fully saturated muscle storage.

This elevation in muscle creatine storage has been correlated with ergogenic benefits discussed in the research section. However, higher doses for longer periods of time are being studied to offset creatine synthesis deficiencies and mitigating diseases.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="creatinedefects" />

Maintenance phase

After the 5–7 day loading phase, muscle creatine stores are fully saturated and supplementation only needs to cover the amount of creatine broken down per day. This maintenance dose was originally reported to be around 2–3 g/day (or 0.03 g/kg/day),<ref name=":2" /> however, some studies have suggested 3–5 g/day maintenance dose to maintain saturated muscle creatine.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name=":6">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Absorption

Endogenous serum or plasma creatine concentrations in healthy adults are normally in a range of 2–12 mg/L. A single 5 gram (5000 mg) oral dose in healthy adults results in a peak plasma creatine level of approximately 120 mg/L at 1–2 hours post-ingestion. Creatine has a fairly short elimination half life, averaging just less than 3 hours, so to maintain an elevated plasma level it would be necessary to take small oral doses every 3–6 hours throughout the day.

Exercise and sport

Creatine supplements are marketed in ethyl ester, gluconate, monohydrate, and nitrate forms.<ref name="Cooper2012">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Creatine supplementation for sporting performance enhancement is considered safe for short-term use but there is a lack of safety data for long term use, or for use in children and adolescents.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

According to a 2018 review article in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition creatine monohydrate is the most effective nutritional supplement to increase high intensity exercise capacity and muscle mass during training.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Creatine use can increase maximum power and performance in high-intensity anaerobic repetitive work (periods of work and rest) by 5% to 15%.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Creatine supplementation exerts positive ergogenic effects on single and multiple bouts of short-duration, high-intensity exercise activities, in addition to potentiating exercise training adaptations.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Creatine has no significant effect on aerobic endurance.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>Template:Obsolete source<ref name="Graham">Template:Cite journal</ref>Template:Obsolete source

A 2014 survey of 21,000 US college athletes showed that 14% of athletes take creatine supplements.<ref name=":1">Template:Cite news</ref>

Research

Cognitive performance

Creatine is sometimes reported to have a beneficial effect on brain function and cognitive processing, although the evidence is difficult to interpret systematically and the appropriate dosing is unknown.<ref name=":8">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name=":9">Template:Cite journal</ref> The greatest effect appears to be in individuals who are stressed (due, for instance, to sleep deprivation) or cognitively impaired.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

A 2018 systematic review found that "generally, there was evidence that short-term memory and intelligence/reasoning may be improved by creatine administration", whereas for other cognitive domains "the results were conflicting".<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

A 2023 meta-analysis including 8 randomized controlled trials found that creatine supplementation improved memory performance with dosing parameters such as intake amounts and duration having no additional effects.<ref name="auto">Template:Cite journal</ref> Any positive effects on cognition from creatine supplementation seem to be greater for older adults.<ref name="auto"/>

A 2024 systematic review found no significant effect for healthy, unstressed individuals and mixed results for people under stress, suggesting that more research is needed to determine optimal dosing parameters and quantify changes in brain creatine levels during supplementation.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

A 2024 randomized trial involving 15 sleep-deprived subjects found that a single large dose of creatine (0.35 g/kg) may partially restore cognitive performance and resolve aberrant brain metabolism parameters.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

In a 2024 scientific opinion article, the European Food Safety Authority Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens determined that a cause and effect relationship cannot be established between creatine supplementation and increased cognitive function based on existing studies.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> In particular, it ruled that there is currently insufficient evidence on the mechanisms by which creatine can impact cognition.

Muscular disease

A meta-analysis found that creatine treatment increased muscle strength in muscular dystrophies, and potentially improved functional performance.<ref name="Kley2013">Template:Cite journal</ref> Creatine treatment does not appear to improve muscle strength in people who have metabolic myopathies.<ref name="Kley2013" /> High doses of creatine lead to increased muscle pain and an impairment in activities of daily living when taken by people who have McArdle disease.<ref name="Kley2013" />

Mitochondrial diseases

Parkinson's disease

Creatine's impact on mitochondrial function has led to research on its efficacy and safety for slowing Parkinson's disease. As of 2014, the evidence did not provide a reliable foundation for treatment decisions, due to risk of bias, small sample sizes, and the short duration of trials.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Huntington's disease

Several primary studies<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> have been completed but no systematic review on Huntington's disease has been completed yet.

ALS

It is ineffective as a treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Testosterone

A 2021 systemic review of studies found that "the current body of evidence does not indicate that creatine supplementation increases total testosterone, free testosterone, DHT or causes hair loss/baldness".<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Cardiovascular disease

A 2011 systematic review evaluated the effectiveness of creatine and creatine analogues in adults with cardiovascular disease, including heart failure and myocardial infarction. The studies assessed the use of various creatine-based compounds—such as creatine, creatine phosphate, and phosphocreatinine—administered via oral, intravenous, or intramuscular routes, typically as adjuncts to standard therapy.

The analysis found no conclusive evidence that creatine or its analogues significantly affect mortality, myocardial infarction progression, or ejection fraction. However, some studies suggested a potential improvement in cardiac dysrhythmias and dyspnoea. The trials varied considerably in terms of drug formulation, dosage, treatment duration, and patient populations. Notably, no studies were identified that examined the effects of these compounds in patients with essential hypertension.

Due to the small sample sizes, clinical heterogeneity, and inconsistent outcomes across trials, the authors concluded that more rigorous and larger-scale studies are necessary to establish the clinical utility of creatine analogues in cardiovascular care.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Pregnancy

It has been found that women who consumed ≥13 mg of creatine per kg of body mass daily have a lower risk of obsetetric conditions. Creatines properties support energy for production, stabilization of maternal plasma creatine, improved pregnancy outcomes, as well as reduced oxidative stress. It was also found to reduce risk of preterm birth, support immunne function, and reduce risk of perinatal brain injry. Perinatal brain injury occurs after hypoxia events, creatine allows cells to recover faster.<ref>Abbie E. Smith-Ryan, Gabrielle M. DelBiondo, Ann F. Brown, Susan M. Kleiner, Nhi T. Tran & Stacey J. Ellery (2025) Creatine in Women’s Health: Bridging the gap from Menstruation Through Pregnancy to Menopause, Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 22:1, 2502094, DOI: 10.1080/15502783.2025.2502094 </ref>

Adverse effects

Side effects include:<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Weight gain due to extra water retention to the muscle

- Potential muscle cramps / strains / pulls

- Upset stomach

- Diarrhea

One well-documented effect of creatine supplementation is weight gain within the first week of the supplement schedule, likely attributable to greater water retention due to the increased muscle creatine concentrations by means of osmosis.<ref name=":0">Template:Cite journal</ref>

A 2009 systematic review discredited concerns that creatine supplementation could affect hydration status and heat tolerance and lead to muscle cramping and diarrhea.<ref name="Lopez RM, Casa DJ, McDermott BP, Ganio MS, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM 2009 215–23">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Dalbo VJ, Roberts MD, Stout JR, Kerksick CM 2008 567–73">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Despite weight gain due to water retention and potential cramps being two seemingly "common" side effects, new research indicates that these side effects are likely not the result of creatine usage. In addition, the initial water retention is attributed to more short-term creatine use (the "loading" phase). Studies have shown that creatine usage does not necessarily affect total body water relative to muscle mass in the long-term.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Renal function

A 2019 systematic review published by the National Kidney Foundation investigated whether creatine supplementation had adverse effects on renal function.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> They identified 15 studies from 1997 to 2013 that looked at standard creatine loading and maintenance protocols of 4–20 g/day of creatine versus placebo. They utilized serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, and serum urea levels as a measure of renal damage. While in general creatine supplementation resulted in slightly elevated creatinine levels that remained within normal limits, supplementation did not induce renal damage (P value< 0.001). Special populations included in the 2019 Systematic review included type 2 diabetic patients<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> and post-menopausal women,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> bodybuilders,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> athletes,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> and resistance trained populations.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The study also discussed 3 case studies where there were reports that creatine affected renal function.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

In a joint statement between the American College of Sports Medicine, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and Dietitians in Canada on performance enhancing nutrition strategies, creatine was included in their list of ergogenic aids and they do not list renal function as a concern for use.<ref name=":7">Template:Cite journal</ref>

The most recent position stand on creatine from the Journal of International Society of Sports Nutrition states that creatine is safe to take in healthy populations from infants to the elderly to performance athletes. They also state that long term (5 years) use of creatine has been considered safe.<ref name=":3">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Safety

Contamination

A 2011 survey of 33 supplements commercially available in Italy found that over 50% of them exceeded the European Food Safety Authority recommendations in at least one contaminant. The most prevalent of these contaminants was creatinine, a breakdown product of creatine also produced by the body.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Creatinine was present in higher concentrations than the European Food Safety Authority recommendations in 44% of the samples. About 15% of the samples had detectable levels of dihydro-1,3,5-triazine or a high dicyandiamide concentration. Heavy metals contamination was not found to be a concern, with only minor levels of mercury being detectable. Two studies reviewed in 2007 found no impurities.<ref name="ReferenceA">Template:Cite book</ref>

Food and cooking

When creatine is mixed with protein and sugar at high temperatures (above 148 °C), the resulting reaction produces carcinogenic heterocyclic amines (HCAs).<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Such a reaction happens when grilling or pan-frying meat.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Creatine content (as a percentage of crude protein) can be used as an indicator of meat quality.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Dietary considerations

Creatine-monohydrate is suitable for vegetarians and vegans, as the raw materials used for the production of the supplement have no animal origin.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

See also

References

External links

- Creatine bound to proteins in the PDB

Template:Subject bar Template:Dietary supplement Template:Authority control