Agate

Template:Short description {{#invoke:other uses|otheruses}} Template:Good article Template:Infobox mineral

Agate (Template:IPAc-en Template:Respell) is a variously translucent, banded variety of chalcedony. Agate stones are characterized by alternating bands of different colored chalcedony and may also include visible quartz crystals. They are common in nature and can be found globally in a large number of different varieties. There are some varieties of chalcedony without bands that are commonly called agate (moss agate, fire agate, etc.); however, these are not true agates. Moreover, not every banded chalcedony is an agate; for example, banded chert forms via different processes and is opaque. Agates primarily form as nodules within volcanic rock, but they can also form in veins or silicified fossils. Agate has been popular as a gemstone in jewelry for thousands of years, and today it is also popular as a collector's stone. Some duller agates sold commercially are artificially treated to enhance their color.

Etymology

Agate was given its name by Theophrastus, a Greek philosopher and naturalist. He discovered the stone Template:Circa along the shoreline of the River Achates (Template:Langx), now the Dirillo River, on the Italian island of Sicily, which at the time was a Greek territory.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Composition

Agate is composed principally of chalcedony,<ref name="mindat" /> a microscopic (microcrystalline) and submicroscopic (cryptocrystalline) form of quartz that grows in fibers. The chemical composition of quartz is Template:Chem2, also known as silica. Normally, between 1% and 20% of the "quartz" in chalcedony is actually moganite, a quartz polymorph.<ref name="chalcedony" /> Unlike macroscopic (macrocrystalline) quartz, which is anhydrous, chalcedony normally contains very small amounts of water bound to its crystal structure.<ref name="chalcedony" /><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Agate contains multiple layers, or bands, of chalcedony fibers.<ref name="mindat" /> The fibers are twisted,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp forming a helical shape.<ref name="PSU" /> There are two different types of chalcedony fibers: length-slow (also known as quartzine) and length-fast. Agate primarily contains length-fast chalcedony fibers, consisting of crystals stacked perpendicular to the c-axis (side to side). Some intergrown quartzine may also be present, consisting of quartz crystals stacked parallel to the c-axis (tip to tip).<ref name="chalcedony">Template:Cite web</ref>

Agate can sometimes contain small amounts of opal, an amorphous, hydrated form of silica.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Agates also frequently contain macrocrystalline quartz, particularly in the center.<ref name="lynch formation" /><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Formation

Geologists generally understand the early stages of agate formation, but the specific processes that result in band development are widely debated. Since they form in cavities within host rock, agate formation cannot be directly observed,<ref name="lynch formation" /> and agate banding has never been successfully replicated in the lab.<ref name="PSU">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="moxon 2017">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Template:AnchorAgates are most commonly found as nodules within the cavities of volcanic rocks<ref name="Moxon" /> such as basalt, andesite, and rhyolite. These cavities, called vesicles (amygdaloids when filled),<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp are gas bubbles that were trapped inside the lava when it cooled.<ref name="Moxon">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="lynch formation">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp The vesicles are later filled with hot, silica-rich water from the surrounding environment, forming a silica gel. This gel crystallizes through a complex process to form agates.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Since agates usually form in lavas poor in free silica, there are multiple theories of where the silica originates from, including micro-shards of silica glass from volcanic ash or tuff deposits and decomposing plant or animal matter.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Agates are much harder than the rocks they form in; some varieties (e.g. Lake Superior agates) are frequently found detached from their host rock.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Template:AnchorIn wall-banded agates, chalcedony fibers grow radially from the vesicle walls inward, perpendicular to the direction of the bands.<ref name="mindat">Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The vesicle walls are often coated with thin layers of celadonite or chlorite,<ref name="lynch formation"/><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp soft, green phyllosilicate minerals that form from the reaction of hot, silica-rich water with the rock.<ref name="lynch formation" /> This coating provides a rough surface for the chalcedony fibers to form on, initially as radial spherulites. The rough surface also causes agate husks to have a pitted appearance once the coating has been weathered away or removed.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Sometimes, the spherulites grow around mineral inclusions, resulting in eyes, tubes, and sagenitic agates.<ref name="mindat" />

The first layer of spherulitic chalcedony is typically clear, followed by successive growth bands of chalcedony alternated with chemically precipitated color bands, primarily iron oxides.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp The center is often macrocrystalline quartz,<ref name="lynch formation" /> which can also occur in bands and possibly forms when there is not enough chemically bound water in the silica gel to promote chalcedony polymerization.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp When the silica concentration of the gel is too low, a hollow center forms, called an agate geode. In geodes, quartz forms crystals around the cavity, with the apex of each crystal pointing towards the center. Occasionally, quartz in agates may be colored, occurring in varieties such as amethyst or smoky quartz.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Template:AnchorLevel-banded agates form when chalcedony precipitates out of solution in the direction of gravity, resulting in horizontal layers of microscopic chalcedony spherulites.<ref name="mindat" /> Level banding commonly occurs together with wall banding, often forming at the base of the vesicle or in the center when the gel stops adhering to the vesicle walls. This is probably due to a decrease in bound water in the gel. Level-banded agate is less dense and less compact than wall-banded agate, as it is less fibrous and more granular.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Enhydro agates, or enhydros, form when liquid water becomes trapped within an agate (or chalcedony) nodule or geode, often long after its formation.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Template:AnchorAgates can also form within rock fissures, called veins.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Vein agates form in a manner similar to nodular agates (see above),<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp and they include lace agates such as blue lace agate and crazy lace agate. Veins may form in either volcanic rock or sedimentary rock.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Less commonly, agates can form as nodules within sedimentary rocks such as limestone, dolomite or tuff. These agates form when silica replaces another mineral, or silica-rich water fills cavities left by decomposed plant or animal matter.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Template:AnchorSedimentary agates also include fossil agates, which form when silica replaces the original composition of an organic material.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> This process is called silicification, a form of petrification. Examples include petrified wood,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> agatized coral,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and Turritella agate (Elimia tenera).<ref name="turritella" /> Although these fossils are often referred to as being "agatized", they are only true agates if they contain bands.<ref name="mindat" />

Structural varieties

Agates are broadly separated into two categories based on the type of banding they exhibit.<ref name="lynch water-level" /><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Wall banding, also called concentric banding or adhesional banding, occurs when agate bands follow the shape of the cavity they formed in. Level banding, also called water-level banding, gravitational banding, horizontal banding, parallel banding, or Uruguay-type banding, occurs when agate bands form in straight, parallel lines. Level banding is less common and usually occurs together with wall banding.<ref name="mindat" />

Wall-banded agates

Template:AnchorFortification agates are any wall-banded agates with tight, well-defined bands.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp They get their name from their appearance which resembles the walls of a fort. Fortification agates are one the most common varieties, and they are what most people think of when they hear the word "agate".<ref name="lynch fortification">Template:Cite book</ref>

Template:AnchorLace agates exhibit a lace-like pattern of bands with many swirls, eyes, bends, and zigzags. Unlike most agates, they usually form in veins instead of nodules.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Template:AnchorFaulted agates have bands that were broken and slightly shifted by rock movement and then re-cemented together by chalcedony. They have the appearance of rock layers with fault lines running through them. Brecciated agates also have bands that were broken apart and re-cemented with chalcedony, but they consist of disjointed band fragments at random angles.<ref name="lynch brecciated">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp They are a form of breccia, which is a textural term for any rock composed of angular fragments.<ref name="lynch brecciated" /><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Template:AnchorEye agates have one or more circular, concentric rings on their surface.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> These "eyes" are actually hemispheres that form on the husk of the agate and extend inward like a bowl.<ref name="lynch eyes">Template:Cite book</ref>

Template:AnchorSagenitic agates, or sagenites, have acicular (needle-shaped) inclusions of another mineral, usually anhydrite, aragonite, goethite, rutile, or a zeolite. Chalcedony often forms tubes around these crystals and may eventually replace the original mineral, resulting in a pseudomorph.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp The term "sagenite" was originally a name for a type of rutile, and later rutilated quartz. It has since been used to describe any quartz variety with acicular inclusions of any mineral.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Template:AnchorTube agates contain tunnel-like structures that extend all the way through the agate.<ref name="lynch tubes">Template:Cite book</ref> These "tubes" may sometimes be banded or hollow, or both. Tube agates form when chalcedony grew around sagenitic inclusions embedded within the agate, forming stalactitic structures. Visible "eyes" can also appear on the surface of tube agates if a cut is made (or the agate is weathered) perpendicular to the stalactitic structure.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Template:AnchorDendritic agates have dark-colored, fern-like patterns (dendrites) that form on the surface or in the spaces between bands.<ref name="lynch dendritic">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp They are composed of manganese or iron oxides. Moss agates exhibit a moss-like pattern and are usually green or brown in color. They form when dendritic structures on the surface of an agate are pushed inward with the silica gel during their formation. Moss agate was once believed to be petrified moss, until it was discovered the moss-like formations are actually composed of celadonite, hornblende, or a chlorite mineral. Plume agates are a type of moss agate, but the dendritic "plumes" form tree-like structures within the agate. They are often bright red (from inclusions of hematite) or bright yellow (from inclusions of goethite).<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp While dendrites frequently occur in banded agates, moss and plume agates usually lack bands altogether. Therefore, they are not true agates according to the mineralogical definition.<ref name="mindat" /><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Template:AnchorIris agates have bands that are fine enough that when thinly sliced, they cause white light to be diffracted into its spectral colors. This "iris effect" usually occurs in colorless agates, but it can also occur in brightly colored ones.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

-

Brazilian agate with classic fortification banding

-

Tumbled Lake Superior eye agates

-

Dendritic agate from India

-

Moss agate cabochons

-

Iris agate from petrified wood

Level-banded agates

Agates with level banding are traditionally called onyx, although the formal definition of the term onyx refers to color pattern, not the shape of the bands.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Accordingly, the name onyx is also used for wall-banded agates. Onyx is also frequently misused as a name for banded calcite. The name originates from the Greek word for the human nail, which has parallel ridges.<ref name="pabian">Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Rp Typically, onyx bands alternate between black and white or other light and dark colors. Sardonyx is a variety with red-to-brown bands alternated with either white or black bands.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Thunder eggs are frequently level-banded, however they may also have wall banding. Level banding is also common in Lake Superior agates.<ref name="lynch water-level">Template:Cite book</ref>

-

Onyx agate

-

Level-banded thunder egg from Oregon, USA

Regional varieties

Agates are very common, and they have been found on every continent,<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp including Antarctica.<ref name="Antarctica" /> In addition to the structural varieties detailed in the previous section, numerous geological, local, and trade names are used to describe agates from different localities.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Below is a table of agate varieties from different regions of the world.Template:Sticky header

| Name | Locality | Region | Description | Type | Geologic environment | Age | Photo(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue lace agate | Namibia | Africa | Pale blue and white lace agate | Vein agate | Volcanic rock (dolomite associated with dolerite) | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | ||

| Template:AnchorBotswana agate | Botswana | Africa | Typically Template:Convert in diameter, with contrasting bands of purple, pink, black, grey, and white | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock (Karoo Series, basalt) | Permian period | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Template:AnchorMalawi agate | Malawi | Africa | Typically bright red or orange with contrasting white bands, some are pink and blue | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock | Permian period | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| (Unnamed agate) | Bellingshausen Station, King George Island | Antarctica | White and clear bands | Nodular agate | <ref name="Antarctica">Template:Cite web</ref> | |||

| Template:AnchorQueensland agate | Queensland | Australia | Often green or yellow-green (colors that are rarely found in other regions), frequently level-banded | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock (basaltic lava flows) | Late Permian period | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| German agate | Near Idar-Oberstein, Germany | Europe | Often red or pink, sometimes other colors | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock | Permian period | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Scottish agate | Stonehaven to just south of Ayr, near Oban, and surrounding the Cheviot Hills, Scotland, United Kingdom | Europe | Various colored bands | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock (andesite) | Early Devonian period | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Small Isles agate | Islands off the west coast of Scotland, United Kingdom | Europe | Various colored bands | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock (basalt) | Tertiary period | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Potato stone (Pot stone) | Bristol and Somerset, England, United Kingdom | Europe | Irregularly-shaped, reddish, banded agate nodules, typically surrounding a hollow cavity lined with macroscopic quartz, but sometimes completely filled | Nodular agate | Sedimentary rock (dolomitic conglomerate and marl) | Triassic period | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Template:AnchorBoley agate | Central Oklahoma, United States | North America | White fortification and eye banding with clasts of brecciated chert | Vein agate | Sedimentary rock (Boley conglomerate layer, Vamoosa formation) | Virgilian series | <ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> | |

| Template:AnchorColdwater agate (Lake Michigan cloud agate) | Great Lakes Region, United States | North America | Banded lines of grey and white chalcedony | Nodular agate | Sedimentary rock (marine limestone and dolomite) | <ref>Template:Cite book</ref> | ||

| Template:AnchorCrazy lace agate | Mexico | North America | Brightly colored lace agate, typically white and red, sometimes yellow and grey | Vein agate | Sedimentary rock | Late Cretaceous period | <ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Template:AnchorDugway geode | Utah, United States | North America | Light grey to blue, often contain hollow cavities lined with drusy quartz | Nodular agate (thunder egg) | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |||

| Fairburn agate | South Dakota and Nebraska, United States | North America | Red fortification banding | Nodular agate | Sedimentary rock (marine carbonate sediments) | Pennsylvanian period | <ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Template:AnchorLaguna agate | Ojo Laguna, Chihuahua, Mexico | North America | Vibrant bands in shades of red, orange, pink, or purple, often exhibit parallax or shadow banding, inclusions common | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock (andesite) | Tertiary period | <ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Lake Superior agate | Near Lake Superior, United States and Canada | North America | Bands in shades of red, orange, yellow, brown, white, and grey, level banding and various structural features common | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock (basalt) | Late Precambrian | <ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="lynch whole book">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Template:AnchorLysite agate | Lysite Mountain, Fremont County, Wyoming, United States | North America | Colorful bands with plumes and moss | Vein agate | Sedimentary rock (marine origin) | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | ||

| Blue Bed (Pony Butte) thunder egg | Richardson Ranch (formerly Priday Ranch), northeast of Madras, Oregon, United States | North America | Blue and white banding with dark brown shell, frequently level-banded | Nodular agate (thunder egg) | Volcanic rock (John Day Formation, rhyolitic volcanic ash) | Miocene epoch | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Template:AnchorHolley (Holly) blue agate | Near Holley, Oregon | North America | Lavender to blue | Nodular agate | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |||

| Template:AnchorSweetwater agate | Near Sweetwater River, Wyoming | North America | Small moss agates with brown or black dendrites, fluorescent under UV light | Nodular agate | Sedimentary rock (sandstone) | Miocene epoch | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Turritella agate | Wyoming | North America | Brown fossil agate with the elongated spiral shells of an extinct freshwater snail (Elimia tenera) | Fossil agate | Sedimentary rock (Green River Formation) | Eocene epoch | <ref name="turritella">Template:Cite web</ref> | |

| Template:AnchorBrazilian agate | Rio Grande do Sul and other southeastern states, Brazil | South America | Often large, up to Template:Convert in diameter and over Template:Convert, commonly pale yellow, gray, or colorless (usually sold artificially dyed), are more colorful or contain structural features | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock (decomposed volcanic ash and basalt) | Late Permian period | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Condor agate | Mendoza, Argentina | South America | Bright red and yellow fortification banding, may contain mossy or sagenitic inclusions | Nodular agate | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |||

| Template:AnchorCrater agate | Patagonia, Argentina | South America | Typically hollow, black with red bands near the center | Nodular agate | Volcanic rock (rhyolite) | Jurassic period | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp | |

| Template:AnchorPuma agate | Andes, Patagonia, Argentina | South America | Agatized coral | Fossil agate | Sedimentary rock (marine) | <ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp |

Uses

Agate is frequently used as a gemstone in jewelry such as pins, brooches, necklaces, earrings, and bracelets. Agates have also historically been used in the art of hardstone carving to make knives, inkstands, seals, marbles, and other objects. Today, they are widely used to make beads, decorative displays, carvings, and cabochons, as well as face-polished and tumble-polished specimens of varying size and origin. Agate collecting is a popular hobby, and agate specimens can be found in numerous gift shops, museums, galleries, and private collections.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Industrial uses of agate exploit its hardness, ability to retain a highly polished surface finish and resistance to chemical attack. Historically, it was used to make bearings for highly accurate laboratory balances and mortars and pestles to crush and mix chemicals. During the Second World War, black agate beads mined from Queensland, Australia were used in the turn and bank indicators of military aircraft.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Agates, particularly moss agates, were first used during the Stone Age to make tools such as arrow and spear points, needles, and hide scrapers. Artifacts from as early as 7000 BCE have been found in Mongolia, and the Natufian people of the Levant are known to have made knives and arrowheads from moss agate as early as 10000 BCE. Agate jewelry from Sumeria has been dated to c. 2500 BCE, and the Ancient Egyptians, Mycenaeans, and Romans all used agate in their jewelry.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Archaeological recovery at the Knossos site on Crete illustrates the role of agates in Bronze Age Minoan culture.<ref>C. Michael Hogan. 2007. Knossos fieldnotes, Modern Antiquarian Template:Webarchive</ref> The ornamental use of agate was common in ancient Greece, in assorted jewelry and in the seal stones of Greek warriors.<ref>Template:Cite magazine</ref>

Idar-Oberstein was a historically important location in Germany that made use of agate on an industrial scale, dating back to c. 1375 CE.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Originally, locally found agates were used to make all types of objects for the European market, but it became a globalized business around the turn of the 20th century. Idar-Oberstein began to import large quantities of agate from Brazil, as ship's ballast. Making use of a variety of proprietary chemical processes, they produced colored beads that were sold around the globe.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

-

A Template:Convert barrel full of tumble-polished agate and jasper

-

Gold Roman signet ring with portrait of emperor Commodus in niccolo agate, 180-200 CE, found in Tongeren, Gallo-Roman Museum (Tongeren)

-

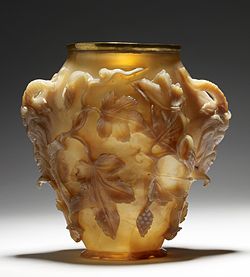

The "Rubens Vase" (Byzantine Empire). Carved in high relief from a single piece of agate, most likely created in an imperial workshop for a Byzantine emperor.

-

Victorian banded agate earrings

-

Patuxent River stone from Maryland — cut and illuminated from behind as a nightlight

-

Agate drinking horn, Tang dynasty

Treatment and processing

Many pale or dull agates are artificially treated to enhance their colors and make them more appealing to consumers. Chalcedony is one of the earliest stones to be artificially enhanced,<ref name="russell">Template:Cite web</ref> with heating having been used for centuries to produce the rich red color of carnelian.<ref name="treated gem">Template:Cite web</ref> Many varieties of chalcedony, including agate, are relatively porous and absorb dyes well.<ref name="russell" /><ref name="treated gem" /> The classical methods<ref name="color loss">Template:Cite journal</ref> of staining agates were developed in the early 19th century in Idar-Oberstein, Germany. After the agates were cut and cleaned, they were soaked for several days in a particular inorganic dye or sugar solution depending on the desired color to be achieved. This was often followed by an acid bath and/or heating ("burning") to oxidize the compounds:<ref name="russell" />

- Blue agates were produced by using a solution of potassium ferricyanide or ferrocyanide followed by iron sulfate, which forms iron ferricyanide (Prussian blue).<ref name="russell" />

- Red agates were produced either by burning alone, or if not enough natural iron was present in the stones, by first soaking them in a solution of iron nitrate and then burning them to form iron oxide.<ref name="russell" />

- Green agates were produced using solutions of nickel or chromium salts followed by burning.<ref name="russell" />

- Black agates were produced by soaking the stones in a sugar solution and then immersing them in sulfuric acid to carbonize the sugars;<ref name="russell" /> brown agates can also be produced using a similar method.<ref name="treated gem" />

- Yellow agates can be produced using hydrochloric acid followed by burning.<ref name="treated gem" />

Organic aniline dyes derived from coal tar began to be used later in the 19th century,<ref name="russell" /> which allowed for the production of agates of additional colors such as pink and purple. While the colors produced by the classical methods are typically permanent, the colors produced by organic dyes can fade with exposure to light or heat.<ref name="color loss" /> Organic dyes can also only penetrate a short distance into the agate from the exposed surfaces. The practice of artificially treating agates remains popular today, and dyed Brazilian agates in particular are very common on the global market.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp

Larger agates are often cut into halves or slices with circular diamond saws. They can then be polished with lapidary grinding, sanding, and polishing wheels of successively greater grit sizes.<ref name="pabian" />Template:Rp Smaller agates and crushed agate fragments can alternatively be polished using rock tumblers or vibratory polishers. This equipment can generate large quantities of silica dust. Respiratory diseases such as silicosis, and a higher incidence of tuberculosis among workers involved in the agate industry, have been studied in India and China.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

See also

Notes

References

External links

- "Agates", School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska-Lincoln (retrieved 27 December 2014).

Template:Silica minerals Template:Gemstones Template:Jewellery Template:Authority control