Eugen Schauman

Template:Short description Template:Infobox person Eugen Waldemar Schauman (Template:Langx; Template:OldStyleDate – Template:OldStyleDate) was a Finnish nationalist activist and member of the noble Schauman family. In 1904, Schauman assassinated Nikolai Bobrikov, the Governor-General of Finland.

Early life and family

Eugen Schauman was born in Kharkov, Russia (now Kharkiv, Ukraine) to Swedish-speaking Finnish parents. His mother was Elin Maria Schauman, and his father was Fredrik Waldemar Schauman, a general-lieutenant in the Imperial Russian army, who also served as a privy councillor and senator in the Finnish government. His brother Rafael was born in 1873, and his sister Sigrid in 1877.<ref name="kansallisbiografia">Template:Cite web</ref> The family moved often due to Waldemar's work with the government.<ref name="kansallisbiografia" />

As a young child, he was inspired by his mother's reading of The Tales of Ensign Stål by Johan Ludvig Runeberg.<ref name="kansallisbiografia"/> Runeberg's tales became an important connection to Schauman's distant homeland, which he longed to see. At the age of eight, Schauman heard that there was a collection going on in Nykarleby, Finland to erect a memorial to the victory over the Russians that had occurred in the 1808 Battle of Jutas in the Finnish War. Inspired by Runeberg's tales, Schauman wanted to contribute to the plan,<ref name="niinistö">Jussi Niinistö: Suomalaisia vapaustaistelijoita, pp. 13–18. Nimox Ky, Helsinki 2003.</ref> and sent a letter from Radom, Poland to Finland that contained a single ruble and read: "Please accept this small contribution to the memorial of Jutas. Eugen Schauman, Radom 24 May 1883"<ref group=notes name="a">The original read: "Var god och emottag denna lilla bidrag (en rubel) till minnesstoden vid Juutas, Eugen Schauman, Radom 24 Maj 1883"</ref> Schauman's mother died the following year, in autumn 1884, when he was nine years old.<ref name="sks">Schauman, Fredrik Waldemar, Suomalaiset kenraalit ja amiraalit Venäjän sotavoimissa 1809–1917. Biography centre, Finnish Literature Society.</ref>

Schauman attended secondary school in Helsinki, Finland while the rest of the family was living in Poland. He had poor hearing, however, and this had an effect on his studies.<ref name="niinistö"/> Nonetheless, Schauman matriculated at the Nya Svenska Läroverket in 1895; graduated from the University of Helsinki with an upper degree in government studies in 1899; and began his career as a clerk in the senate in 1901. He was a temporary employee working as an assistant to the school governing board. The job became permanent in 1903.<ref name="matrikkeli">Eugen Schauman. Ylioppilasmatrikkeli 1853–1899; online publication of the University of Helsinki.</ref><ref name="niinistö"/><ref name="zetterberg"/> In addition to his job at the senate, Schauman arranged for a series of marksmanship courses aimed at local students in Helsinki. These courses later became a part of the White Guards training.Template:Citation needed

Political activism

Language manifesto

Schauman observed and experienced the formalization of the controversial policy of Russification firsthand with the February 1899 decree of the February Manifesto. His father, Waldemar Schauman, resigned as senator in the summer 1900 as a protest against the manifesto, that had made the Russian language a compulsory subject in all Finnish schools. At first Schauman acted against the oppression like the other students: joining protests at the Runeberg statue; spreading leaflets calling for the will to battle and hatred towards the Russians; and gathering names for the Great Petition in Uusimaa.<ref name="niku">Risto Niku: Ministeri Ritavuoren murha, pp. 30–42. Edita, Helsinki 2004.</ref>

Shooting practice

Gradually Schauman, like other students and activists, started to move from passive resistance to active resistance. He organised shipments of weapons from abroad by shipping American rifles to Finland with the help of the Finnish Hunting Association, which were then distributed to students. In addition to this, he organised shooting clubs around the Helsinki area that taught marksmanship to students and other youths. Soon Schauman and other activists started planning an armed revolution.<ref group=notes name="b">After Bobrikov's assassination, a home search conducted at Lieutenant General Waldemar Schauman's house found a plan to found general shooting clubs in Finland.</ref> As well as his father's loss of his job, Schauman was angered by the dismissal of his uncle, Colonel Theodor Schauman, from the command of the Finnish Dragoon Regiment, a unit from Lappeenranta, in December 1901, after Nikolai Bobrikov had not been satisfied with his inspection of it.<ref name="niku"/>

Draft riot

Schauman became personally involved with Russian authorities during the riots in Helsinki connected to the draft strikes on 18 April 1902. Thousands of Finns participated in demonstrations at Senate Square angered by the draft conducted at the Russian Guard barracks. The governor of the Uusimaa Province, Mikhail Kaigorodov, had sent the Cossacks to end the demonstrations. Schauman was returning from work to his home on Koulukatu, but went to see what was happening on the square. A group of a few Cossacks intercepted him on Hallituskatu, pushed him against a wall, and started to whip him on the head. When one of the Cossacks went for his sabre, Schauman took his knife and stabbed at his chest. The blade of the knife twisted when it hit a metal part of the Cossack's uniform. The Cossack was, however, thrown off his horse and Schauman escaped to the stairway of the chemistry building of the university. According to a witness, he was "...shaking with anger...".<ref>Seppo Zetterberg: Viisi laukausta senaatissa: Eugen Schaumanin elämä ja teko. Otava, Helsinki 1986. Template:ISBN</ref>Template:Rp

Kagal

After the Cossack riots, Bobrikov became convinced that Finland was undergoing a kramola (or "secret rebellion"). The Tsar awarded Bobrikov dictatorial powers in 1902. As the Russian oppression worsened, the underground passive-resistance organisation, Kagal, decided that it was time to move to stronger acts of defiance, as passive-resistance methods were no longer effective. For example, in 1902 over half of the age class had skipped the draft to the Russian army, which had been made mandatory for Finns. In 1903 the draft strike was no longer as effective, and only 22 percent skipped the draft. "Emergency measures", meaning assassination, was accepted as a new way to act against the strengthening Russification. Many leading Kagal members had already been exiled at this point. At first, the plan was to strike against Finnish politicians agreeing with the Russification, but soon the activists, the Kagal organization, and Schauman decided it was best to strike against the Governor-General Nikolai Bobrikov, who was seen as the leader and main activist of the oppression politics.<ref name="niku"/>

Assassination

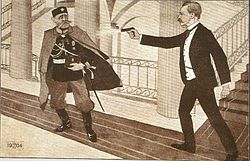

The possible assassination of Bobrikov was a topical question among the Finnish activists of the time. Other activist groups are known to have made assassination plans, but Schauman convinced them to give him two weeks before they would intervene.<ref name="kansallisbiografia"/> When Bobrikov came to the Senate house on 16 June, Schauman shot him three times—and then himself twice in the chest—using an FN Browning M1900 pistol.<ref>Gunwriters' Handloading Subsonic Cartridges, Part 2, P.T. Kekkonen, 1999. Accessed on 12 May 2011.</ref> Schauman died instantly. Two of the bullets that hit Bobrikov ricocheted off his military decorations, but the third bounced back from his buckle and caused severe damage to his stomach. Bobrikov did not die immediately but was taken to the Helsinki Surgical Hospital. Surgeon Template:Ill worked to save his life, but Bobrikov died the following day at 1:10 a.m.<ref name="hskirurgi">Template:Cite news</ref><ref name="kansallisbiografia"/><ref name="ksml">Template:Cite news</ref>

Aftermath

Schauman's body was taken to an unmarked grave in the Malmi cemetery in Helsinki. After the political situation eased up he was reburied in the Schauman family grave in the Template:Ill and a monument was built on the grave.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Schauman's legacy

Schauman left a letter in which he stated that he justified his actions as a punishment for Bobrikov's crimes against the people of Finland. He addressed the letter to the Tsar and wanted him to pay attention to the problems in the whole of the Russian empire, especially in Poland and the Baltic Sea region. He claimed he had acted alone and emphasized that his family was not involved in the assassination.<ref name="kirje">Template:Cite web</ref>

Schauman became something of an icon for the resistance to Imperial Russia, and many Finns still consider him a hero. His fame can be characterized by his ranking as the 34th greatest Finn of all time in the 2004 Suuret suomalaiset (Greatest Finns) television poll. At the location of the assassination in the hallway of the Council of State, there is a memorial plaque that states Se Pro Patria Dedit ("He Gave Himself for His Country"). Jean Sibelius composed the funeral march In Memoriam in memory of him.<ref name="Sibelius">Template:Cite web</ref>

Historical perspective

The importance of Schauman in history divides opinions.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In the summer of 2004, a hundred years after Bobrikov's murder, Prime Minister Matti Vanhanen condemned the act, calling Schauman a terrorist.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> According to him, events like the assassination of Bobrikov are not appropriate to celebrate in the era of the war on terror.<ref>Template:Cite magazine</ref> A discussion arose from the statement, in which Unto Vesa, amanuensis of the Peace and Conflict Research Institute, agreed with Vanhanen.<ref>Ruotuväki 8/2006Template:Dead link, Joonas Nordman: "Pahat pojat ja tytöt". (in Finnish)</ref>

{{#invoke:Gallery|gallery}}

Notes

References

External links

- Template:Commons category-inline

- Centennial article about the assassination in Helsingin Sanomat international edition, 15 June 2004

- 1875 births

- 1904 suicides

- People from Kharkiv

- People from Kharkovsky Uyezd

- 19th-century Finnish nobility

- 20th-century Finnish nobility

- Swedish-speaking Finns

- Finnish people of German descent

- Finnish assassins

- Finnish nationalists

- Nationalist assassins

- Suicides by firearm in Finland

- Multiple gunshot suicides

- Murder–suicides in Finland