Fractal

Template:General geometryTemplate:Short description {{#invoke:other uses|otheruses}}

Template:Use mdy dates Template:Anchor

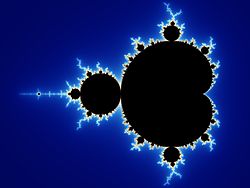

In mathematics, a fractal is a geometric shape containing detailed structure at arbitrarily small scales, usually having a fractal dimension strictly exceeding the topological dimension. Many fractals appear similar at various scales, as illustrated in successive magnifications of the Mandelbrot set.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /><ref name="Falconer" /><ref name="patterns" /><ref name="vicsek"/> This exhibition of similar patterns at increasingly smaller scales is called self-similarity, also known as expanding symmetry or unfolding symmetry; if this replication is exactly the same at every scale, as in the Menger sponge, the shape is called affine self-similar.<ref name="Gouyet" /> Fractal geometry relates to the mathematical branch of measure theory by their Hausdorff dimension.

One way that fractals are different from finite geometric figures is how they scale. Doubling the edge lengths of a filled polygon multiplies its area by four, which is two (the ratio of the new to the old side length) raised to the power of two (the conventional dimension of the filled polygon). Likewise, if the radius of a filled sphere is doubled, its volume scales by eight, which is two (the ratio of the new to the old radius) to the power of three (the conventional dimension of the filled sphere). However, if a fractal's one-dimensional lengths are all doubled, the spatial content of the fractal scales by a power that is not necessarily an integer and is in general greater than its conventional dimension.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983">Template:Cite book</ref> This power is called the fractal dimension of the geometric object, to distinguish it from the conventional dimension (which is formally called the topological dimension).<ref name="Mandelbrot Chaos">Template:Cite book</ref>

Analytically, many fractals are nowhere differentiable.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /><ref name="vicsek" /> An infinite fractal curve can be conceived of as winding through space differently from an ordinary line – although it is still topologically 1-dimensional, its fractal dimension indicates that it locally fills space more efficiently than an ordinary line.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /><ref name="Mandelbrot Chaos" />

Starting in the 17th century with notions of recursion, fractals have moved through increasingly rigorous mathematical treatment to the study of continuous but not differentiable functions in the 19th century by the seminal work of Bernard Bolzano, Bernhard Riemann, and Karl Weierstrass,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> and on to the coining of the word fractal in the 20th century with a subsequent burgeoning of interest in fractals and computer-based modelling in the 20th century.<ref name="classics" /><ref name="MacTutor" />

There is some disagreement among mathematicians about how the concept of a fractal should be formally defined. Mandelbrot himself summarized it as "beautiful, damn hard, increasingly useful. That's fractals."<ref>Template:Cite webTemplate:Cbignore</ref> More formally, in 1982 Mandelbrot defined fractal as follows: "A fractal is by definition a set for which the Hausdorff–Besicovitch dimension strictly exceeds the topological dimension."<ref>Mandelbrot, B. B.: The Fractal Geometry of Nature. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York (1982); p. 15.</ref> Later, seeing this as too restrictive, he simplified and expanded the definition to this: "A fractal is a rough or fragmented geometric shape that can be split into parts, each of which is (at least approximately) a reduced-size copy of the whole."<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /> Still later, Mandelbrot proposed "to use fractal without a pedantic definition, to use fractal dimension as a generic term applicable to all the variants".<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

The consensus among mathematicians is that theoretical fractals are infinitely self-similar iterated and detailed mathematical constructs, of which many examples have been formulated and studied.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /><ref name="Falconer" /><ref name="patterns">Template:Cite book</ref> Fractals are not limited to geometric patterns, but can also describe processes in time.<ref name="Gouyet" /><ref name="vicsek" /><ref name="time series" /> Fractal patterns with various degrees of self-similarity have been rendered or studied in visual, physical, and aural media<ref name="music">Template:Cite journal</ref> and found in nature,<ref name="heart" /><ref name="cerebellum">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="neuroscience">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="branching" /> technology,<ref name="soil">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="diagnostic imaging">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="medicine">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="seismology" /> art,<ref name="novel" /><ref name="African art" /> and architecture.<ref name="springer.com 9783319324241">Ostwald, Michael J., and Vaughan, Josephine (2016) The Fractal Dimension of Architecture Birhauser, Basel. Template:Doi.</ref> Fractals are of particular relevance in the field of chaos theory because they show up in the geometric depictions of most chaotic processes (typically either as attractors or as boundaries between basins of attraction).<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Etymology

The term "fractal" was coined by the mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot in 1975.<ref>Benoît Mandelbrot, Objets fractals, 1975, p. 4</ref> Mandelbrot based it on the Latin Template:Lang, meaning "broken" or "fractured", and used it to extend the concept of theoretical fractional dimensions to geometric patterns in nature.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /><ref name="Mandelbrot quote">Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite OED</ref>

Introduction

The word "fractal" often has different connotations for mathematicians and the general public, where the public is more likely to be familiar with fractal art than the mathematical concept. The mathematical concept is difficult to define formally, even for mathematicians, but key features can be understood with a little mathematical background.

The feature of "self-similarity", for instance, is easily understood by analogy to zooming in with a lens or other device that zooms in on digital images to uncover finer, previously invisible, new structure. If this is done on fractals, however, no new detail appears; nothing changes and the same pattern repeats over and over, or for some fractals, nearly the same pattern reappears over and over. Self-similarity itself is not necessarily counter-intuitive (e.g., people have pondered self-similarity informally such as in the infinite regress in parallel mirrors or the homunculus, the little man inside the head of the little man inside the head ...). The difference for fractals is that the pattern reproduced must be detailed.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" />Template:Rp<ref name="Falconer" /><ref name="Mandelbrot quote" />

This idea of being detailed relates to another feature that can be understood without much mathematical background: Having a fractal dimension greater than its topological dimension, for instance, refers to how a fractal scales compared to how geometric shapes are usually perceived. A straight line, for instance, is conventionally understood to be one-dimensional; if such a figure is rep-tiled into pieces each 1/3 the length of the original, then there are always three equal pieces. A solid square is understood to be two-dimensional; if such a figure is rep-tiled into pieces each scaled down by a factor of 1/3 in both dimensions, there are a total of 32 = 9 pieces.

We see that for ordinary self-similar objects, being n-dimensional means that when it is rep-tiled into pieces each scaled down by a scale-factor of 1/r, there are a total of rn pieces. Now, consider the Koch curve. It can be rep-tiled into four sub-copies, each scaled down by a scale-factor of 1/3. So, strictly by analogy, we can consider the "dimension" of the Koch curve as being the unique real number D that satisfies 3D = 4. This number is called the fractal dimension of the Koch curve; it is not the conventionally perceived dimension of a curve. In general, a key property of fractals is that the fractal dimension differs from the conventionally understood dimension (formally called the topological dimension).

This also leads to understanding a third feature, that fractals as mathematical equations are "nowhere differentiable". In a concrete sense, this means fractals cannot be measured in traditional ways.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /><ref name="vicsek" /><ref name="Gordon" /> To elaborate, in trying to find the length of a wavy non-fractal curve, one could find straight segments of some measuring tool small enough to lay end to end over the waves, where the pieces could get small enough to be considered to conform to the curve in the normal manner of measuring with a tape measure. But in measuring an infinitely "wiggly" fractal curve such as the Koch snowflake, one would never find a small enough straight segment to conform to the curve, because the jagged pattern would always re-appear, at arbitrarily small scales, essentially pulling a little more of the tape measure into the total length measured each time one attempted to fit it tighter and tighter to the curve. The result is that one must need infinite tape to perfectly cover the entire curve, i.e. the snowflake has an infinite perimeter.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" />

History

The history of fractals traces a path from chiefly theoretical studies to modern applications in computer graphics, with several notable people contributing canonical fractal forms along the way.<ref name="classics">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="MacTutor">Template:Cite web</ref> A common theme in traditional African architecture is the use of fractal scaling, whereby small parts of the structure tend to look similar to larger parts, such as a circular village made of circular houses.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> According to Pickover, the mathematics behind fractals began to take shape in the 17th century when the mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz pondered recursive self-similarity (although he made the mistake of thinking that only the straight line was self-similar in this sense).<ref name="Pickover">Template:Cite book</ref>

In his writings, Leibniz used the term "fractional exponents", but lamented that "Geometry" did not yet know of them.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" />Template:Rp Indeed, according to various historical accounts, after that point few mathematicians tackled the issues and the work of those who did remained obscured largely because of resistance to such unfamiliar emerging concepts, which were sometimes referred to as mathematical "monsters".<ref name="Gordon" /><ref name="classics" /><ref name="MacTutor" /> Thus, it was not until two centuries had passed that on July 18, 1872 Karl Weierstrass presented the first definition of a function with a graph that would today be considered a fractal, having the non-intuitive property of being everywhere continuous but nowhere differentiable at the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences.<ref name="classics" />Template:Rp<ref name="MacTutor" />

In addition, the quotient difference becomes arbitrarily large as the summation index increases.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Not long after that, in 1883, Georg Cantor, who attended lectures by Weierstrass,<ref name="MacTutor" /> published examples of subsets of the real line known as Cantor sets, which had unusual properties and are now recognized as fractals.<ref name="classics" />Template:Rp Also in the last part of that century, Felix Klein and Henri Poincaré introduced a category of fractal that has come to be called "self-inverse" fractals.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" />Template:Rp

One of the next milestones came in 1904, when Helge von Koch, extending ideas of Poincaré and dissatisfied with Weierstrass's abstract and analytic definition, gave a more geometric definition including hand-drawn images of a similar function, which is now called the Koch snowflake.<ref name="classics" />Template:Rp<ref name="MacTutor" /> Another milestone came a decade later in 1915, when Wacław Sierpiński constructed his famous triangle then, one year later, his carpet. By 1918, two French mathematicians, Pierre Fatou and Gaston Julia, though working independently, arrived essentially simultaneously at results describing what is now seen as fractal behaviour associated with mapping complex numbers and iterative functions and leading to further ideas about attractors and repellors (i.e., points that attract or repel other points), which have become very important in the study of fractals.<ref name="vicsek" /><ref name="classics" /><ref name="MacTutor" />

Very shortly after that work was submitted, by March 1918, Felix Hausdorff expanded the definition of "dimension", significantly for the evolution of the definition of fractals, to allow for sets to have non-integer dimensions.<ref name="MacTutor" /> The idea of self-similar curves was taken further by Paul Lévy, who, in his 1938 paper Plane or Space Curves and Surfaces Consisting of Parts Similar to the Whole, described a new fractal curve, the Lévy C curve.<ref group="notes" name="levy note" />

Different researchers have postulated that without the aid of modern computer graphics, early investigators were limited to what they could depict in manual drawings, so lacked the means to visualize the beauty and appreciate some of the implications of many of the patterns they had discovered (the Julia set, for instance, could only be visualized through a few iterations as very simple drawings).<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" />Template:Rp<ref name="Gordon">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="MacTutor" /> That changed, however, in the 1960s, when Benoit Mandelbrot started writing about self-similarity in papers such as How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> which built on earlier work by Lewis Fry Richardson.

In 1975,<ref name="Mandelbrot quote" /> Mandelbrot solidified hundreds of years of thought and mathematical development in coining the word "fractal" and illustrated his mathematical definition with striking computer-constructed visualizations. These images, such as of his canonical Mandelbrot set, captured the popular imagination; many of them were based on recursion, leading to the popular meaning of the term "fractal".<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="Gordon" /><ref name="classics" /><ref name="Pickover" />

In 1980, Loren Carpenter gave a presentation at the SIGGRAPH where he introduced his software for generating and rendering fractally generated landscapes.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Definition and characteristics

One often cited description that Mandelbrot published to describe geometric fractals is "a rough or fragmented geometric shape that can be split into parts, each of which is (at least approximately) a reduced-size copy of the whole";<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /> this is generally helpful but limited. Authors disagree on the exact definition of fractal, but most usually elaborate on the basic ideas of self-similarity and the unusual relationship fractals have with the space they are embedded in.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /><ref name="Gouyet">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="Falconer">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="vicsek" /><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

One point agreed on is that fractal patterns are characterized by fractal dimensions, but whereas these numbers quantify complexity (i.e., changing detail with changing scale), they neither uniquely describe nor specify details of how to construct particular fractal patterns.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> In 1975 when Mandelbrot coined the word "fractal", he did so to denote an object whose Hausdorff–Besicovitch dimension is greater than its topological dimension.<ref name="Mandelbrot quote" /> However, this requirement is not met by space-filling curves such as the Hilbert curve.<ref group=notes name="space filling note" />

Because of the trouble involved in finding one definition for fractals, some argue that fractals should not be strictly defined at all. According to Falconer, fractals should be only generally characterized by a gestalt of the following features;<ref name="Falconer" />

- Self-similarity, which may include:

- Exact self-similarity: identical at all scales, such as the Koch snowflake

- Quasi self-similarity: approximates the same pattern at different scales; may contain small copies of the entire fractal in distorted and degenerate forms; e.g., the Mandelbrot set's satellites are approximations of the entire set, but not exact copies.

- Statistical self-similarity: repeats a pattern stochastically so numerical or statistical measures are preserved across scales; e.g., randomly generated fractals like the well-known example of the coastline of Britain for which one would not expect to find a segment scaled and repeated as neatly as the repeated unit that defines fractals like the Koch snowflake.<ref name="vicsek" />

- Qualitative self-similarity: as in a time series<ref name="time series">Template:Cite book</ref>

- Multifractal scaling: characterized by more than one fractal dimension or scaling rule

- Fine or detailed structure at arbitrarily small scales. A consequence of this structure is fractals may have emergent properties<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> (related to the next criterion in this list).

- Irregularity locally and globally that cannot easily be described in the language of traditional Euclidean geometry other than as the limit of a recursively defined sequence of stages. For images of fractal patterns, this has been expressed by phrases such as "smoothly piling up surfaces" and "swirls upon swirls";<ref name="Mandelbrot Chaos" />see Common techniques for generating fractals.

As a group, these criteria form guidelines for excluding certain cases, such as those that may be self-similar without having other typically fractal features. A straight line, for instance, is self-similar but not fractal because it lacks detail, and is easily described in Euclidean language without a need for recursion.<ref name="Mandelbrot1983" /><ref name="vicsek" />

When Mandelbrot introduced the term fractal, he excluded magnification range as a defining characteristic in order to accommodate physical fractals with more limited ranges than their mathematical counterparts.<ref> B.B. Mandelbrot, "The Fractal Geometry of Nature" New York: W.H. Freeman & Company 1982 </ref>

Common techniques for generating fractals

Template:See also Template:Anchor

Template:Anchor Images of fractals can be created by fractal generating programs. Because of the butterfly effect, a small change in a single variable can have an unpredictable outcome.

- Iterated function systems (IFS) – use fixed geometric replacement rules; may be stochastic or deterministic;<ref name="IFS">Template:Cite book</ref> e.g., Koch snowflake, Cantor set, Haferman carpet,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Sierpinski carpet, Sierpinski gasket, Peano curve, Harter-Heighway dragon curve, T-square, Menger sponge

- Strange attractors – use iterations of a map or solutions of a system of initial-value differential or difference equations that exhibit chaos (e.g., see multifractal image, or the logistic map)

- L-systems – use string rewriting; may resemble branching patterns, such as in plants, biological cells (e.g., neurons and immune system cells<ref name="branching" />), blood vessels, pulmonary structure,<ref name="modeling vasculature" /> etc. or turtle graphics patterns such as space-filling curves and tilings

- Escape-time fractals – use a formula or recurrence relation at each point in a space (such as the complex plane); usually quasi-self-similar; also known as "orbit" fractals; e.g., the Mandelbrot set, Julia set, Burning Ship fractal, Nova fractal and Lyapunov fractal. The 2d vector fields that are generated by one or two iterations of escape-time formulae also give rise to a fractal form when points (or pixel data) are passed through this field repeatedly.

- Template:AnchorRandom fractals – use stochastic rules; e.g., Lévy flight, percolation clusters, self avoiding walks, fractal landscapes, trajectories of Brownian motion and the Brownian tree (i.e., dendritic fractals generated by modeling diffusion-limited aggregation or reaction-limited aggregation clusters).<ref name="vicsek">Template:Cite book</ref>

- Finite subdivision rules – use a recursive topological algorithm for refining tilings<ref name="finite">J. W. Cannon, W. J. Floyd, W. R. Parry. Finite subdivision rules. Conformal Geometry and Dynamics, vol. 5 (2001), pp. 153–196.</ref> and they are similar to the process of cell division.<ref name="biol">Template:Cite book</ref> The iterative processes used in creating the Cantor set and the Sierpinski carpet are examples of finite subdivision rules, as is barycentric subdivision.

Applications

Simulated fractals

Fractal patterns have been modeled extensively, albeit within a range of scales rather than infinitely, owing to the practical limits of physical time and space. Models may simulate theoretical fractals or natural phenomena with fractal features. The outputs of the modelling process may be highly artistic renderings, outputs for investigation, or benchmarks for fractal analysis. Some specific applications of fractals to technology are listed elsewhere. Images and other outputs of modelling are normally referred to as being "fractals" even if they do not have strictly fractal characteristics, such as when it is possible to zoom into a region of the fractal image that does not exhibit any fractal properties. Also, these may include calculation or display artifacts which are not characteristics of true fractals.

Modeled fractals may be sounds,<ref name="music" /> digital images, electrochemical patterns, circadian rhythms,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> etc. Fractal patterns have been reconstructed in physical 3-dimensional space<ref name="medicine" />Template:Rp and virtually, often called "in silico" modeling.<ref name="modeling vasculature" /> Models of fractals are generally created using fractal-generating software that implements techniques such as those outlined above.<ref name="vicsek" /><ref name="time series" /><ref name="medicine" /> As one illustration, trees, ferns, cells of the nervous system,<ref name="branching" /> blood and lung vasculature,<ref name="modeling vasculature">Template:Cite book</ref> and other branching patterns in nature can be modeled on a computer by using recursive algorithms and L-systems techniques.<ref name="branching" />

The recursive nature of some patterns is obvious in certain examples—a branch from a tree or a frond from a fern is a miniature replica of the whole: not identical, but similar in nature. Similarly, random fractals have been used to describe/create many highly irregular real-world objects, such as coastlines and mountains. A limitation of modeling fractals is that resemblance of a fractal model to a natural phenomenon does not prove that the phenomenon being modeled is formed by a process similar to the modeling algorithms.

Natural phenomena with fractal features

Approximate fractals found in nature display self-similarity over extended, but finite, scale ranges. The connection between fractals and leaves, for instance, is currently being used to determine how much carbon is contained in trees.<ref>"Hunting the Hidden Dimensional". Nova. PBS. WPMB-Maryland. October 28, 2008.</ref> Phenomena known to have fractal features include:

- Actin cytoskeleton<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Algae

- Animal coloration patterns

- Blood vessels and pulmonary vessels<ref name="modeling vasculature" />

- Brownian motion (generated by a one-dimensional Wiener process).<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

- Clouds and rainfall areas<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Coastlines <ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Craters

- Crystals<ref name="crystal">Template:Cite book</ref>

- DNA

- Dust grains<ref>Template:Citation</ref>

- Earthquakes<ref name="seismology">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

- Fault lines

- Geometrical optics<ref name="geomopt">Template:Citation</ref>

- Heart rates<ref name="heart">Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Heart sounds

- Lake shorelines and areas<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Lightning bolts

- Mountain-goat horns

- Neurons

- Polymers

- Percolation

- Mountain ranges

- Ocean waves<ref name="nature">Template:Cite book</ref>

- Pineapple

- Proteins<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Psychedelic experience<ref> Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Purkinje cells<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Rings of Saturn<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- River networks<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Romanesco broccoli

- Snowflakes<ref name="snowflake">Template:Cite book</ref>

- Soil pores<ref>Ozhovan M. I., Dmitriev I. E., Batyukhnova O. G. Fractal structure of pores of clay soil. Atomic Energy, 74, 241–243 (1993).</ref>

- Surfaces in turbulent flows<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Trees <ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Protein complexes<ref>Template:Cite journal </ref>

-

Frost crystals occurring naturally on cold glass form fractal patterns

-

Fractal basin boundary in a geometrical optical system<ref name="geomopt"/>

-

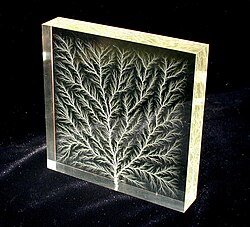

A fractal is formed when pulling apart two glue-covered acrylic sheets

-

High-voltage breakdown within a Template:Convert block of acrylic glass creates a fractal Lichtenberg figure

-

Romanesco broccoli, showing self-similar form approximating a natural fractal

-

Fractal defrosting patterns, polar Mars. The patterns are formed by sublimation of frozen CO2. Width of image is about a kilometer.

-

Slime mold Brefeldia maxima growing fractally on wood

Fractals in cell biology

Fractals often appear in the realm of living organisms where they arise through branching processes and other complex pattern formation. Richard Taylor and co-workers have shown that the dendritic branches of neurons form fractal patterns.<ref> J.H. Smith, C. Rowland, B. Harland, S. Moslehi, K. Schobert, R.M. Montgomery, W.J. Watterson, J. Dalrymple-Alford, R.P. Taylor, "How Neurons Exploit Fractal Geometry to Maximize Physical Connectivity", Scientific Reports, 11, 2332 (2021) </ref> Ian Wong and co-workers have shown that migrating cells can form fractals by clustering and branching.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Nerve cells function through processes at the cell surface, with phenomena that are enhanced by largely increasing the surface to volume ratio. As a consequence nerve cells often are found to form into fractal patterns.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> These processes are crucial in cell physiology and different pathologies.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Multiple subcellular structures also are found to assemble into fractals. Diego Krapf has shown that through branching processes the actin filaments in human cells assemble into fractal patterns.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Similarly Matthias Weiss showed that the endoplasmic reticulum displays fractal features.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The current understanding is that fractals are ubiquitous in cell biology, from proteins, to organelles, to whole cells.

In creative works

Fractal expressionism is used to distinguish fractal art generated directly by artists from fractal art generated using mathematics and/or computers.<ref>R.P.Taylor, A.P. Micolich and D. Jonas, Fractal Expressionism, Physics World, 25, October 1999.</ref>

Since 1999 numerous scientific groups have performed fractal analysis on over 50 paintings created by Jackson Pollock by pouring paint directly onto horizontal canvasses, see for example.<ref>Taylor, Richard P., Adam P. Micolich, and David Jonas. "Fractal Analysis of Pollock's Drip Paintings." Nature 399.6735 (1999): 422. Print.</ref><ref>J.R. Mureika, C.C. Dyer, G.C. Cupchik, "Multifractal Structure in Nonrepresentational Art", Physical Review E, vol. 72, 046101-1-15 (2005).</ref><ref name="C. Redies, J 2007">C. Redies, J. Hasenstein and J. Denzler, "Fractal-Like Image Statistics in Visual Art: Similar to Natural Scenes", Spatial Vision, vol. 21, 137-148 (2007).</ref><ref name="S. Lee, S 2007">S. Lee, S. Olsen and B. Gooch, "Simulating and Analyzing Jackson Pollock's Paintings" Journal of Mathematics and the Arts, vol.1, 73-83 (2007).</ref><ref>J. Alvarez-Ramirez, C. Ibarra-Valdez, E. Rodriguez and L. Dagdug, "1/f-Noise Structure in Pollock's Drip Paintings", Physica A, vol. 387, 281-295 (2008).</ref><ref name="D.J. Field, 2008">D.J. Graham and D.J. Field, "Variations in Intensity for Representative and Abstract Art, and for Art from Eastern and Western Hemispheres" Perception, vol. 37, 1341-1352 (2008).</ref><ref>J. Alvarez-Ramirez, J. C. Echeverria, E. Rodriguez "Performance of a High-Dimensional R/S Analysis Method for Hurst Exponent Estimation" Physica A, vol. 387, 6452-6462 (2008).</ref><ref>J. Coddington, J. Elton, D. Rockmore and Y. Wang, "Multi-fractal Analysis and Authentication of Jackson Pollock Paintings", Proceedings SPIE, vol. 6810, 68100F 1-12 (2008).</ref><ref>M. Al-Ayyoub, M. T. Irfan and D.G. Stork, "Boosting Multi-Feature Visual Texture Classifiers for the Authentification of Jackson Pollock's Drip Paintings", SPIE proceedings on Computer Vision and Image Analysis of Art II, vol. 7869, 78690H (2009).</ref><ref>J.R. Mureika and R.P. Taylor, "The Abstract Expressionists and Les Automatistes: multi-fractal depth", Signal Processing, vol. 93 573 (2013).</ref><ref>R.P. Taylor et al, "Authenticating Pollock Paintings Using Fractal Geometry", Pattern Recognition Letters, vol. 28, 695-702 (2005).</ref><ref>K Zheng et al Vis Comput. DOI 10.1007/s00371-014-0985-7</ref><ref>E De la Calleja et al Annals of Physics, Vol. 371, 313 (2016)</ref> In 2015, fractal analysis was used to achieve a 93% success rate in distinguishing real from imitation Pollocks.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> A 2024 study used an artificial intelligence technique based on fractals to achieve a 99% success rate.<ref> J.H. Smith, C. Holt, N.H. Smith, R.P. Taylor "Using Machine Learning to Distinguish Between Authentic and Imitation Jackson Pollock Poured Paintings: A Tile Driven Approach to Computeraon", "n anOl ne" vol. 19, e0302962 (2024) </ref>

Decalcomania, a technique used by artists such as Max Ernst, can produce fractal-like patterns.<ref>Frame, Michael; and Mandelbrot, Benoît B.; A Panorama of Fractals and Their Uses Template:Webarchive</ref> It involves pressing paint between two surfaces and pulling them apart.

Cyberneticist Ron Eglash has suggested that fractal geometry and mathematics are prevalent in African art, games, divination, trade, and architecture. Circular houses appear in circles of circles, rectangular houses in rectangles of rectangles, and so on. Such scaling patterns can also be found in African textiles, sculpture, and even cornrow hairstyles.<ref name="African art">Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Hokky Situngkir also suggested the similar properties in Indonesian traditional art, batik, and ornaments found in traditional houses.<ref>Situngkir, Hokky; Dahlan, Rolan (2009). Fisika batik: implementasi kreatif melalui sifat fraktal pada batik secara komputasional. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. Template:ISBN</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Ethnomathematician Ron Eglash has discussed the planned layout of Benin city using fractals as the basis, not only in the city itself and the villages but even in the rooms of houses. He commented that "When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture very disorganised and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn't even discovered yet."<ref>Koutonin, Mawuna (March 18, 2016). "Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace". Retrieved April 2, 2018.</ref>

In a 1996 interview with Michael Silverblatt, David Foster Wallace explained that the structure of the first draft of Infinite Jest he gave to his editor Michael Pietsch was inspired by fractals, specifically the Sierpinski triangle (a.k.a. Sierpinski gasket), but that the edited novel is "more like a lopsided Sierpinsky Gasket".<ref name="novel">Template:Cite web</ref>

Some works by the Dutch artist M. C. Escher, such as Circle Limit III, contain shapes repeated to infinity that become smaller and smaller as they get near to the edges, in a pattern that would always look the same if zoomed in.

-

A fractal that models the surface of a mountain (animation)

-

3D recursive image

-

Recursive fractal butterfly image

Biophilic fractals are patterns designed to induce the health and well-being benefits associated with exposure to nature's scenery.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> These include stress-reduction and enhanced cognitive capacity. Designers and architects incorporate biophilic fractals into the built environment to counter the fact that people spend 92% of their time indoors and away from nature's scenery. The Fractal Chapel designed by INNOCAD architecture in the state hospital in Graz, Austria, is a prominent example and recipient of the 2025 IIDA (International Interior Design Association) Best of Competition Award.

Physiological responses: Fractal Fluency

Fractal fluency is a neuroscience model that proposes that, through exposure to nature's fractal scenery, people's visual systems have adapted to efficiently process fractals with ease. This adaptation occurs at many stages of the visual system, from the way people's eyes move to which regions of the brain get activated.<ref> R.P. Taylor, C. Viengkham, J.H. Smith, C. Rowland, S. Moslehi, S. Stadlober, A. Lesjak, M. Lesjak, B. Spehar, "Fractal Fluency: Processing of Fractal Stimuli Across Sight, Sound and Touch", The Fractal Geometry of the Brain, Edition II, Advances in Neurobiology, vol 36. 907-934, Springer, 2024. </ref> Fluency puts the viewer in a 'comfort zone' so inducing an aesthetic experience. Neuroscience experiments have shown that Jackson Pollock's fractal paintings induce the same positive physiological responses in the observer as nature's fractals and mathematical fractals.<ref name="R.P. Taylor, B. Spehar 2011">R.P. Taylor, B. Spehar, P. Van Donkelaar and C.M. Hagerhall, "Perceptual and Physiological Responses to Jackson Pollock's Fractals," Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 5 1- 13 (2011).</ref> This shows that fractal expressionism is related to fractal fluency by providing motivation for artists, such as Pollock, to use Fractal Expressionism in their art to appeal to people.

Humans appear to be especially well-adapted to processing fractal patterns with fractal dimension between 1.3 and 1.5.<ref> R.P. Taylor, "The Potential of Biophilic Fractal Designs to Promote Health and Performance: A Review of Experiments and Applications" Journal of Sustainability: Special edition "Architecture and Salutogenesis: Beyond Indoor Environmental Quality" vol. 13, 823 (2021) </ref> When humans view fractal patterns with fractal dimensions in this range, these fractals reduce physiological stress and boost cognitive abilities.<ref name="Taylor 2006">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Applications in technology

- Fractal Bionics<ref> R.P. Taylor, "The Interdisciplinary Journey to Fractal Bionics" Invited Article for Physics Today, 44-50 December 2024 </ref>

- Fractal antennas<ref name="antenna">Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Fractal transistor<ref name="Fractal transistor">Template:Cite book</ref>

- Fractal heat exchangers<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

- Digital imaging

- Architecture<ref name="springer.com 9783319324241"/>

- Urban growth<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

- Classification of histopathology slides

- Fractal landscape or Coastline complexity

- Detecting 'life as we don't know it' by fractal analysis<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Enzymes (Michaelis–Menten kinetics)

- Generation of new music

- Signal and image compression

- Creation of digital photographic enlargements

- Fractal in soil mechanics

- Computer and video game design

- Computer graphics

- Organic environments

- Procedural generation

- Fractography and fracture mechanics

- Small angle scattering theory of fractally rough systems

- T-shirts and other fashion

- Generation of patterns for camouflage, such as MARPAT

- Digital sundial

- Technical analysis of price series

- Fractals in networks

- Medicine<ref name="medicine" />

- Neuroscience<ref name="cerebellum" /><ref name="neuroscience" />

- Diagnostic imaging<ref name="diagnostic imaging" />

- Pathology<ref name="pathology">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Geology<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Geography<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Archaeology<ref name="archaeology">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Soil mechanics<ref name="soil" />

- Seismology<ref name="seismology" />

- Search and rescue<ref name="search and rescue">Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Morton order space filling curves for GPU cache coherency in texture mapping,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> rasterisation<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and indexing of turbulence data.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

See also

Template:Portal Template:Div col

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

Notes

References

Further reading

- Stanley, Eugene H, Ostrowsky, N. (editors); On Growth and Fractal Form Fractal and Non-Fractal Patterns in Physics, Martinus Nijhoff Publisher, 1986. Template:ISBN

- Barnsley, Michael F.; and Rising, Hawley; Fractals Everywhere. Boston: Academic Press Professional, 1993. Template:Isbn

- Duarte, German A.; Fractal Narrative. About the Relationship Between Geometries and Technology and Its Impact on Narrative Spaces. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2014. Template:Isbn

- Falconer, Kenneth; Techniques in Fractal Geometry. John Wiley and Sons, 1997. Template:Isbn

- Jürgens, Hartmut; Peitgen, Heinz-Otto; and Saupe, Dietmar; Chaos and Fractals: New Frontiers of Science. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1992. Template:Isbn

- Mandelbrot, Benoit B.; The Fractal Geometry of Nature. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co., 1982. Template:Isbn

- Peitgen, Heinz-Otto; and Saupe, Dietmar; eds.; The Science of Fractal Images. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1988. Template:Isbn

- Pickover, Clifford A.; ed.; Chaos and Fractals: A Computer Graphical Journey – A 10 Year Compilation of Advanced Research. Elsevier, 1998. Template:Isbn

- Jones, Jesse; Fractals for the Macintosh, Waite Group Press, Corte Madera, CA, 1993. Template:Isbn.

- Lauwerier, Hans; Fractals: Endlessly Repeated Geometrical Figures, Translated by Sophia Gill-Hoffstadt, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ, 1991. Template:Isbn, cloth. Template:Isbn paperback. "This book has been written for a wide audience..." Includes sample BASIC programs in an appendix.

- Template:Cite book

- Wahl, Bernt; Van Roy, Peter; Larsen, Michael; and Kampman, Eric; Exploring Fractals on the Macintosh, Addison Wesley, 1995. Template:Isbn

- Lesmoir-Gordon, Nigel; The Colours of Infinity: The Beauty, The Power and the Sense of Fractals. 2004. Template:Isbn (The book comes with a related DVD of the Arthur C. Clarke documentary introduction to the fractal concept and the Mandelbrot set.)

- Liu, Huajie; Fractal Art, Changsha: Hunan Science and Technology Press, 1997, Template:Isbn.

- Gouyet, Jean-François; Physics and Fractal Structures (Foreword by B. Mandelbrot); Masson, 1996. Template:Isbn, and New York: Springer-Verlag, 1996. Template:Isbn. Out-of-print. Available in PDF version at.Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite book

External links

Template:Commons Template:Wikibooks

- Template:Webarchive

- "Hunting the Hidden Dimension", PBS NOVA, first aired August 24, 2011

- Benoit Mandelbrot: Fractals and the Art of Roughness ([1]), TED, February 2010

- Equations of self-similar fractal measure based on the fractional-order calculus(2007)

- Oriental Five Elements Fractal

Template:Fractals Template:Chaos theory Template:Mathematical art Template:Patterns in natureTemplate:GeometryTemplate:Authority control