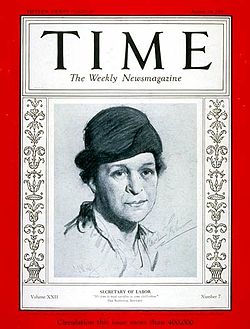

Frances Perkins

Template:Short description Template:Use American English Template:Use mdy dates Template:Infobox officeholder Frances Perkins (born Fannie Coralie Perkins; April 10, 1880<ref name="1880Census">Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> – May 14, 1965) was an American workers-rights advocate who served as the fourth United States Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945, the longest serving in that position. A member of the Democratic Party, Perkins was the first woman ever to serve in a presidential cabinet. As a loyal supporter of her longtime friend, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, she helped make labor issues important in the emerging New Deal coalition. She advocated for immigrants’ rights as well. She was one of two Roosevelt cabinet members to remain in office for his entire presidency (the other being Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes).

Perkins's most important role came in developing a policy for social security in 1935. She also helped form government policy for working with labor unions, although some union leaders distrusted her. Perkins's Labor Department helped to mediate strikes by way of the United States Conciliation Service. She dealt with numerous labor issues during World War II, when skilled labor was vital to the economy and women were moving into jobs formerly held by men.<ref name=":1">Downey, Kirstin. The Woman Behind the New Deal, 2009, p. 250.</ref>

Perkins was born in Boston. After graduating from Mount Holyoke College, she briefly worked as a teacher and at the Hull House settlement in Chicago. She obtained graduate degrees at Columbia University and became a labor leader and consumer advocate in New York City, where she first met Roosevelt in 1910. Perkins was appointed a commissioner in New York City government and later in the state government. As the head of Roosevelt's Industrial Commission when he was governor of New York, she addressed the early effects of the Great Depression. When Roosevelt was elected president in 1932, Perkins was asked to join his cabinet and she presented him with a list of programs to help workers. She oversaw many New Deal programs during the Depression and labor programs during World War II. The Frances Perkins Building, headquarters of the U.S. Labor Department, is named for her, and she is remembered with a feast day in the Episcopal Church.

Early life

Fannie Coralie Perkins was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to Susan Ella Perkins (née Bean; 1849–1927) and Frederick William Perkins (1844–1916), the owner of a stationer's business (both of her parents originally were from Maine).<ref name=1880Census/> Fannie Perkins had one sister, Ethel Perkins Harrington (1884–1965).<ref name=":5">Template:Cite news</ref> The family could trace their roots to colonial America, and the women had a tradition of work in education.<ref name="Parkhurst, Crusader, page 4" /> She spent much of her childhood in Worcester, Massachusetts. Frederick loved Greek literature and passed that love on to Fannie.<ref name=":5" />

Perkins attended the Classical High School in Worcester. She earned a bachelor's degree in chemistry and physics from Mount Holyoke College in 1902. While attending Mount Holyoke, Perkins discovered progressive politics and the suffrage movement.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> She was named class president.<ref name=":5" /> One of her professors was Annah May Soule, who assigned students to tour a factory to study working conditions;<ref>Annah May Soule Papers Template:Webarchive, Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections, South Hadley, MA.</ref> Perkins recalled Soule's course as an important influence.<ref name=":2" />

Early career and continuing education

After college, Perkins held a variety of teaching positions, including one from 1904 to 1906 where she taught chemistry at Ferry Hall School (now Lake Forest Academy), an all-girls school in Lake Forest, Illinois.<ref name=":2">Template:Cite web</ref> In Chicago, she volunteered at settlement houses, including Hull House, where she worked with Jane Addams.<ref name=":2" /> She changed her name from Fannie to Frances<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> when she joined the Episcopal church in 1905.<ref name="Kennedy, Susan E 2000">Kennedy, Susan E. "Perkins, Frances". American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press, Feb. 2000. Web. March 27, 2013.</ref> In 1907, she moved to Philadelphia and enrolled at University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School to learn economics, and spent two years in the city working as a social worker.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> During this time, she joined the Socialist Party of America,<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> but left after a few years as she felt the party was too idealistic.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Shortly after, she moved to Greenwich Village, New York, where she attended Columbia University and became active in the suffrage movement. In support of the movement, Perkins attended protests and meetings, and advocated for the cause on street corners. She earned a master's degree in economics and sociology from Columbia in 1910.<ref>Downey, Kristin. The Woman Behind the New Deal. Anchor Books, 2010, pp. 11, 25.</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In 1910 Perkins achieved statewide prominence as head of the New York office of the National Consumers League<ref name="francesperkinscenter.org">Template:Cite web</ref> and lobbied with vigor for better working hours and conditions. She also taught as a professor of sociology at Adelphi College.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The next year, she witnessed the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, a pivotal event in her life.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The factory employed hundreds of workers, mostly young women, but lacked fire escapes. In addition, the owner kept all the doors and stairwells locked in order to prevent employees from taking breaks. When the building caught fire, many workers tried unsuccessfully to escape through the windows.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Just a year before, these same women and girls had fought for the 54-hour work week and other benefits that Perkins had championed. One hundred and forty-six workers died. Perkins blamed lax legislation for the loss.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

As a consequence of this fire, Perkins left her position at the New York office of the National Consumers League and, on the recommendation of Theodore Roosevelt, became the executive secretary for the Committee on Safety of the City of New York, formed to improve fire safety.<ref name="Kennedy, Susan E 2000" /><ref name=":8">Template:Cite news</ref> As part of the Committee on Safety, Perkins investigated another significant fire at the Freeman plant in Binghamton, New York, in which 63 people died. In 1912,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> she was instrumental in getting the New York legislature to pass a "54-hour" bill that capped the number of hours women and children could work.<ref name="Parkhurst, Crusader, page 3">Template:Cite news</ref><ref name="francesperkinscenter.org"/> Perkins pressed for votes for the legislation, encouraging proponents including Franklin D. Roosevelt to filibuster, while Perkins called state senators to make sure they could be present for the final vote.<ref name="Parkhurst, Crusader, page 3" />

Marriage and personal life

In 1913, Perkins married New York economist Paul Caldwell Wilson.<ref name="Parkhurst, Crusader, page 4" /> She kept her maiden name because she did not want her activities in Albany and New York City to affect the career of her husband, then the secretary to the New York City mayor.<ref name="Parkhurst, Crusader, page 4" /> She defended her right to keep her maiden name in court.<ref name="Parkhurst, Crusader, page 4">Template:Cite news. This newspaper article does not make any reference to an actual court case. The phrase that she "defended her right to keep her maiden name in court" was often used in newspaper articles about her, but even in Downey's recent biography of 2009, there is no mention of such a court proceeding.</ref> The couple had a daughter, Susanna, born in December 1916.<ref name=":11">Template:Cite web</ref> Less than two years later, Wilson began to show signs of mental illness.<ref name=":11" /> He would be institutionalized frequently for mental illness throughout the remainder of their marriage.<ref>Downey, Kirstin. The Woman Behind the New Deal, 2009, p. 2.</ref> Perkins had cut back slightly on her public life following the birth of her daughter, but returned after her husband's illness to provide for her family.<ref name="Shiff">Template:Cite book</ref> According to biographer Kirstin Downey, Susanna displayed "manic-depressive symptoms", as well.<ref>Downey, Kirstin. The Woman Behind the New Deal, 2009, p. 380.</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Perkins shared the Georgetown, D.C. home of an old friend, Mary Harriman Rumsey, who had founded the Junior League in 1901, for less than 17 months, until Rumsey's death in 1934. Rumsey and Perkins's arrangement was for practical reasons, as a December 1933 Washington Post columnist had criticized Perkins for not meeting social obligations, due to her apartment accommodations. Later Perkins shared a home with Caroline O’Day, a Democratic congresswoman from New York.<ref name=":1" /><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Return to work in New York

Prior to moving to Washington, D.C., Perkins held various positions in the New York state government. She had gained respect from the political leaders in the state. In 1919, she was added to the Industrial Commission of the State of New York by Governor Al Smith.<ref name="Kennedy, Susan E 2000"/> Her nomination was met with protests from both manufacturers and labor, neither of whom felt Perkins represented their interests.<ref name=":9">Template:Cite news</ref> Smith stood by Perkins as someone who could be a voice for women and girls in the workforce and for her work on the Wagner Factory Investigating Committee.<ref name=":9" /> Although claiming the delay in Perkins's confirmation was not due to her gender, some state senators pointed to Perkins's not taking her husband's name as a sign that she was a radical.<ref name=":10">Template:Cite news</ref> Perkins was confirmed on February 18, 1919, becoming one of the first female commissioners in New York, and began working out of New York City.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name=":10" /> The state senate-confirmed position made Perkins one of three commissioners overseeing the industrial code, and the supervisor of both the bureau of information and statistics and the bureau of mediation and arbitration.<ref name=":10" /> The position also came with an $8,000 salary (Template:Inflation), making Perkins the highest-paid woman in New York state government.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> Six months into her job, her fellow Commissioner James M. Lynch called Perkins's contributions "invaluable," and added "[f]rom the work which Miss Perkins has accomplished I am convinced that more women ought to be placed in high positions throughout the state departments."<ref name=":10" />

In 1929, the newly elected New York governor, Franklin Roosevelt, appointed Perkins as the inaugural New York state industrial commissioner.<ref>Our History – New York State Department of Labor Template:Webarchive. Labor.ny.gov (March 25, 1911). Retrieved on 2013-08-12.</ref><ref name="Parkhurst, Crusader, page 4" /> As commissioner, Perkins supervised an agency with 1,800 employees.<ref name="Parkhurst, Crusader, page 4" />

Having earned the co-operation and the respect of various political factions, Perkins helped put New York in the forefront of progressive reform. She expanded factory investigations, reduced the workweek for women to 48 hours, and championed minimum wage and unemployment insurance laws. She worked vigorously to put an end to child labor and to provide safety for women workers.<ref name="Kennedy, Susan E 2000"/>

Secretary of Labor

In 1933, Roosevelt summoned Perkins to ask her to join his cabinet. Perkins presented Roosevelt with a long list of labor programs for which she would fight, from Social Security to minimum wage. "Nothing like this has ever been done in the United States before," she told Roosevelt. "You know that, don’t you?"<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Agreeing to back her, Roosevelt nominated Perkins as Secretary of Labor. The nomination was met with support from the National League of Women Voters and the Women's Party.<ref name=":6">Template:Cite news</ref> The American Federation of Labor criticized the selection of Perkins because of a perceived lack of ties to labor.<ref name=":6" />

As secretary, Perkins oversaw the Department of Labor. Perkins went on to hold the position for 12 years, longer than any other Secretary of Labor and the fourth longest of any cabinet secretary.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> She also became the first woman to hold a cabinet position in the United States, thus she became the first woman to enter the presidential line of succession.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The selection of a woman to the cabinet had been rumored in the four previous administrations, with Roosevelt being the first to follow through.<ref name=":7">Template:Cite news</ref> Roosevelt had witnessed Perkins's work firsthand during their time in Albany.<ref name=":7" /> With few exceptions, President Roosevelt consistently supported the goals and programs of Secretary Perkins.

Perkins was “the central architect of the New Deal”<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and played a major role in its development by formulating policy, guiding legislation, and directing implementation.<ref name="francesperkinscenter.org" /> As chair of the President's Committee on Economic Security, she was involved in all aspects of its advisory reports, including the Civilian Conservation Corps and the She-She-She Camps.<ref name="Kennedy, Susan E 2000" /> Her most important contribution was to help design the Social Security Act of 1935;<ref>Thomas N.Bethell, "Roosevelt Redux". American Scholar 74.2 (2005): 18–31 online, a popular account.</ref><ref>G. John Ikenberry, and Theda Skocpol, "Expanding social benefits: The role of social security." Political Science Quarterly 102.3 (1987): 389-416. online</ref> her role as chair of the Committee prepared the groundwork for what would ultimately become a landmark piece of legislation.<ref name=":0" />

Perkins created the Immigration and Naturalization Service.<ref name=":3">Template:Cite journal</ref> She sought to implement liberal immigration policies but some of her efforts experienced pushback, especially in Congress.<ref name=":3" /> Her goal to humanize the treatment of immigrants in the U.S. nonetheless led to some noteworthy successes in standing up against restrictive immigration practices, abolishing, for instance, the Bureau of Immigration’s “Section 24” squad, known for their illegal apprehension tactics which violated due process.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Perkins went to Geneva between June 11 and 18, 1938. On June 13, she gave a speech at the International Labour Organization in which she called on the organization to make its contribution to the world economic recovery, while avoiding being dragged into political problems. She also defended the participation of the United States in the ILO, which it had joined in 1934<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>Template:Refn.

In 1939, she came under fire from some members of Congress for refusing to deport the communist head of the West Coast International Longshore and Warehouse Union, Harry Bridges. Ultimately, Bridges was vindicated by the Supreme Court.<ref>Template:Cite magazine</ref>

After the death of President Roosevelt in April 1945, Harry Truman replaced the Roosevelt cabinet, naming Lewis B. Schwellenbach as Secretary of Labor.<ref name="Wilmington morning star, Future Cabinet">Template:Cite news</ref><ref name="Evening star, Four New Cabinet">Template:Cite news</ref> Perkins's tenure as secretary ended on June 30, 1945, with the swearing in of Schwellenbach.<ref name="Evening star, Four New Cabinet" />

Later life

Following her tenure as Secretary of Labor, in 1945, Perkins was asked by President Truman to serve on the United States Civil Service Commission,<ref name=":0" /> which she accepted. In her post as commissioner, Perkins spoke out against government officials requiring secretaries and stenographers to be physically attractive, blaming the practice for the shortage of secretaries and stenographers in the government.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> Perkins left the Civil Service Commission in 1952 when her husband died.<ref name=":0">Template:Cite web</ref> During this period, she also published a memoir of her time in the Roosevelt administration entitled, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946, Template:ISBN), which covered her personal history with Franklin Roosevelt, starting from their meeting in 1910.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Following her government service career, Perkins remained active and returned to educational positions at colleges and universities. She was a teacher and lecturer at the New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University until her death in 1965, at age 85. She also gave guest lectures at other universities, including two 15-lecture series at the University of Illinois Institute of Labor and Industrial relations in 1955 and 1958.<ref>Soderstrom, Carl; Soderstrom, Robert; Stevens, Chris; Burt, Andrew (2018). Forty Gavels: The Life of Reuben Soderstrom and the Illinois AFL-CIO. 3. Peoria, IL: CWS Publishing. p. 42. Template:ISBN.</ref>

At Cornell, she lived at the Telluride House where she was one of the first women to become a member of that renowned intellectual community. Kirstin Downey, author of The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR's Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, dubbed her time at the Telluride House "probably the happiest phase of her life".<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Perkins is buried in the Glidden Cemetery in Newcastle, Maine.<ref>"CAM Cover Story". Cornell Alumni Magazine.com (May 17, 1965). Retrieved on 2013-08-12.</ref> She was also known locally as "Mrs. Paul Wilson" and is buried by that name.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Legacy

Perkins is famous for being the first woman cabinet member, as well as from her policy accomplishments. She was heavily involved with many issues associated with the social safety net including, the creation of Social Security, unemployment insurance in the United States, the federal minimum wage, and federal laws regulating child labor.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Frances Perkins championed the rights of immigrants. In her role as cabinet secretary, she facilitated the immigration of thousands of Jews to the U.S. from Germany and other European nations who were escaping Nazi persecution in the 1930s—including hundreds of Jewish children in collaboration with German Jewish Children's Aid—all in the face of American antisemitism and a restrictive immigration system.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In 1967, the Telluride House and Cornell University's School of Industrial and Labor Relations established the Frances Perkins Memorial Fellowship.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> In 1982, Perkins was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In 2015, Perkins was named by Equality Forum as one of their 31 Icons of the 2015 LGBT History Month.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In 2019, she was announced as among the members of the inaugural class of the Government Hall of Fame.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Also that year, Elizabeth Warren used a podium built with wood salvaged from the Perkins Homestead.<ref>Template:Cite magazine</ref>

Character in historical context

Perkins’s leadership has had a profound impact on women’s history in the United States by leading the way for women as they assume powerful roles in government.<ref name=":0" /> Yet, as the first woman to become a member of the presidential cabinet, Perkins had an unenviable challenge: she had to be as capable, as fearless, as tactful, and as politically astute as the other Washington politicians, in order to make it possible for other women to be accepted into the halls of power after her.<ref>The Tennessean, Arts & Entertainment, March 8, 2009, "The Woman Behind the New Deal" (Kirstin Downey). "Perkins ...not only had to do more than her male counterparts to prove herself, but she had to do it while dealing with rough-and-tumble labor leaders, a husband in and out of mental institutions, condescending bureaucrats and some Congress members hell-bent on impeaching her." p. 11.</ref>

Perkins had a cool personality that held her aloof from the crowd. On one occasion, however, she engaged in some heated name-calling with Alfred P. Sloan, the chairman of the board at General Motors. During a punishing United Auto Workers strike, she phoned Sloan in the middle of the night and called him a scoundrel and a skunk for not meeting the union's demands. She said, "You don't deserve to be counted among decent men. You'll go to hell when you die." Sloan's late-night response was one of irate indignation.<ref>Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, p. 68, Random House, New York, 2012. Template:ISBN.</ref>

Her achievements indicate her great love of workers and lower-class groups, but her conservative upbringing held her back from mingling freely and exhibiting personal affection. She was well-suited for the high-level efforts to effect sweeping reforms, but never caught the public's eye or its affection.<ref>Frances Perkins Collection. Mount Holyoke College Archives</ref>

Memorials and monuments

President Jimmy Carter renamed the headquarters of the U.S. Department of Labor in Washington, D.C., the Frances Perkins Building in 1980.<ref name=":12">Template:Cite news</ref> Perkins was honored with a postage stamp that same year.<ref name="NPM">Template:Cite web</ref> Her home in Washington, D.C. from 1937 to 1940, and her Maine family home are both designated National Historic Landmarks.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

The Frances Perkins Center is a nonprofit organization located at the Frances Perkins Homestead in Newcastle, Maine, which was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 2014.<ref name=":4">Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In December 2024, the site was named a National Monument by President Joe Biden.<ref>Megerian, Chris et. al, "Biden establishes a national monument for Frances Perkins, the 1st female Cabinet secretary". Associated Press. Published December 16, 2024. Accessed December 16, 2024.</ref>

On April 10, 2003, a historical marker honoring Perkins was dedicated in Homestead, Pennsylvania, at the southwest corner of 9th and Amity.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

On October 30, 2024, a plaque honoring Perkins was unveiled at 121 Washington Place in Greenwich Village, where Perkins once lived.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Perkins remains a prominent alumna of Mount Holyoke College, whose Frances Perkins Program allows "women of non-traditional age" (i.e., age 24 or older) to complete a bachelor of arts degree. There are approximately 140 Frances Perkins scholars each year.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Maine Department of Labor mural

A mural depicting Perkins was displayed in the Maine Department of Labor headquarters,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> the native state of her parents. On March 23, 2011, Maine's Republican governor, Paul LePage, ordered the mural removed. A spokesperson for the governor said he received complaints about the mural from state business officials and an "anonymous" fax charging that it was reminiscent of "communist North Korea where they use these murals to brainwash the masses".<ref name="mural">Template:Cite news</ref> LePage also ordered that the names of seven conference rooms in the state department of labor be changed, including one named after Perkins.<ref name="mural" /> A lawsuit was filed in U.S. District Court seeking "to confirm the mural's current location, ensure that the artwork is adequately preserved, and ultimately to restore it to the Department of Labor's lobby in Augusta".<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Template:As of, the mural resides in the Maine State Museum, at the entrance to the Maine State Library and Maine State Archives.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Veneration

In 2022, Frances Perkins was officially added to the Episcopal Church liturgical calendar with a feast day on 13 May.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In popular culture

Perkins is a minor character in the 1977 Broadway musical Annie, in which she, alongside Harold Ickes, is ordered by Roosevelt to sing along to the song Tomorrow with the title character.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> It is during this scene in the show that Roosevelt's cabinet comes up with the idea of the New Deal.

In the 1987 American movie Dirty Dancing, the lead character Frances "Baby" Houseman reveals that she was named after Perkins.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

David Brooks's 2015 book The Road to Character includes an extensive chapter biography of Perkins.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Becoming Madam Secretary<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> is a novel by New York Times author Stephanie Dray that tells the story of Ms. Perkins’s life. It was copyrighted in 2024 and published by Berkley, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC in hard cover and paperback editions and by Thorndike Press in a large-type edition.

See also

- List of female United States Cabinet members

- List of United States Cabinet members who have served more than eight years

- Silicosis

Notes

References

Bibliography

- Colman, Penny. A Woman Unafraid: The Achievements of Frances Perkins (1993) online

- Downey, Kirstin. The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR's Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, (New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2009). Template:ISBN.

- Graham, Rebecca Brenner. Dear Miss Perkins: A Story of Frances Perkins's Efforts to Aid Refugees from Nazi Germany. New York: Citadel Press, Kensington Publishing Corp., 2025. Template:ISBN

- Keller, Emily. Frances Perkins: First Woman Cabinet Member. (Greensboro: Morgan Reynolds Publishing, 2006). Template:ISBN.

- Leebaert, Derek. Unlikely Heroes: Franklin Roosevelt, His Four Lieutenants, and the World They Made (2023); on Perkins, Ickes, Wallace and Hopkins.

- Levitt, Tom. The Courage to Meddle: the Belief of Frances Perkins. (London, KDP, 2020). Template:ISBN.

- Martin, George Whitney. Madam Secretary: Frances Perkins. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1976. Template:ISBN. online.

- Myers, Elisabeth P. Madam Secretary: Frances Perkins (1972) online

- Pasachoff, Naomi. Frances Perkins: Champion of the New Deal. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. Template:ISBN.

- Pirro, Jeanine Ferris. "Reforming the urban workplace: the legacy of Frances Perkins." Fordham Urban Law Journal (1998): 1423+ online.

- Prieto, L. C., Phipps, S. T. A., Thompson, L. R. and Smith, X. A. “Schneiderman, Perkins, and the early labor movement”, Journal of Management History (2016), 22#1 pp. 50–72.

- Severn, Bill. Frances Perkins: A Member of the Cabinet. New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1976. Template:ISBN. online

- Williams, Kristin S., and Albert J. Mills. "Frances Perkins: gender, context and history in the neglect of a management theorist". Journal of Management History (2017). 23#1: 23–50. Frances Perkins: gender, context and history in the neglect of a management theorist

Primary sources

- Perkins, Frances. The Roosevelt I Knew (Viking Press, 1947). online

External links

Template:Library resources box Template:Commons category

- President Biden designates new national monument at Frances Perkins Center in Maine

- Frances Perkins Center

- Audio recording of Perkins lecture at Cornell

- Template:Internet Archive film clip

- Frances Perkins Collection at Mount Holyoke College Template:Webarchive

- Perkins Papers at Mount Holyoke College Template:Webarchive

- Frances Perkins Collection. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

- Notable New Yorkers – Frances PerkinsTemplate:SndBiography, photographs, and interviews of Frances Perkins from the Notable New Yorkers collection of the Oral History Research Office at Columbia University

- Columbians Ahead of Their Time, Frances Perkins biography

- Frances Perkins. Correspondence and Memorabilia. 5017. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University.

- Frances Perkins Lectures at the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University.

- Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project: Frances Perkins

- U.S. Department of Labor Biography

- "Biographer Chronicles Perkins, 'New Deal' Pioneer", All Things Considered, March 28, 2009. An interview with Kirstin Downey about her biography of Frances Perkins.

- "Remembering Social Security's Forgotten Shepherd", Morning Edition, August 12, 2005. Penny Colman and Linda Wertheimer Discuss Frances Perkins

- Remarkable Frances Perkins in Twin Cities in 1935 – Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois newspaper)

- Template:PM20

- "Summoned: Frances Perkins and the General Welfare" (Documentary available on PBS.org)

Template:S-start Template:S-off Template:S-bef Template:S-ttl Template:S-aft Template:S-end

Template:USSecLabor Template:Truman cabinet Template:FD Roosevelt cabinet Template:New Deal Template:National Women's Hall of Fame Template:Authority control

- 1880 births

- 1965 deaths

- 20th-century New York (state) politicians

- 20th-century American women politicians

- American Episcopalians

- Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations faculty

- Mount Holyoke College alumni

- Politicians from Boston

- Politicians from Worcester, Massachusetts

- Socialist Party of America politicians from New York (state)

- New York (state) Democrats

- Franklin D. Roosevelt administration cabinet members

- State cabinet secretaries of New York (state)

- Truman administration cabinet members

- United States secretaries of labor

- Women members of the Cabinet of the United States

- First women government ministers

- Workers' education