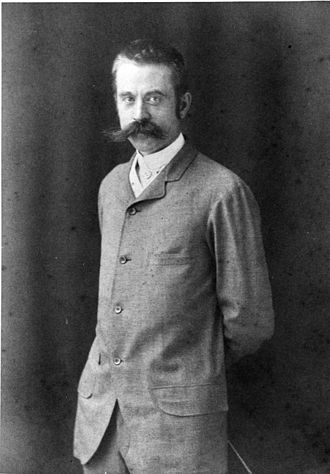

Harry Kendall Thaw

Template:Short description Template:Use mdy dates

Template:Tone Template:Infobox person

Harry Kendall Thaw (February 12, 1871 – February 22, 1947)<ref name=obit/><ref name=thaw/> was the son of American businessman William Thaw Sr. Heir to a multimillion-dollar fortune, he is most notable for having shot and killed architect Stanford White in front of hundreds of witnesses at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden on June 25, 1906. Thaw's trial for murder was heavily publicized and called the "trial of the century". After one hung jury, a second jury found Thaw not guilty by reason of insanity.

Thaw had harbored an obsessive hatred of White, believing he had blocked Thaw's access to the social elite of New York City. White also had a previous romantic relationship with Thaw's wife, the model and chorus girl Evelyn Nesbit. This affair allegedly began with White plying Nesbit with alcohol and then raping her while she was unconscious. In Thaw's mind, this relationship had "ruined" Nesbit.

Plagued by mental illness throughout his life (evident even in childhood), Thaw spent lavishly to fund his obsessive partying, drug addiction and sexual gratification. The Thaw family's wealth allowed them to buy the silence of anyone who threatened to reveal Thaw's licentious transgressions. However, Thaw had serious confrontations with the criminal justice system, one of which resulted in seven years of confinement in a mental institution.

Early life

Harry Thaw was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania,<ref>Lucas, Doug. "Harry Thaw – The Notorious Playboy of Old Allegheny" Allegheny City Society Reporter Dispatch (Summer 2007)</ref> on February 12, 1871, to Pittsburgh businessman William Thaw Sr.,<ref name=obit/><ref name=thaw/> and his second wife, Mary Sibbet Thaw (Template:Née Copley). Thaw's father fathered eleven children from his two marriages.<ref name=obit /> Thaw had five siblings: Edward (born 1873), Josiah (born 1874), Margaret (born 1877) and Alice Cornelia (born 1880).<ref>"Benjamin Thaw" Profiles in Time BlogSpot website (February 26, 2007). Retrieved: July 20, 2012</ref> A brother, born a year before Harry, died an accidental death in infancy, smothered by his mother's breast while he lay in her bed.<ref name="Uruburu193">Uruburu, p. 193</ref> Thaw's mother was known for her episodes of ungovernable temper and her abusive treatment of the family's servants.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 296, 309</ref>

In childhood, Thaw was subject to bouts of insomnia, temper tantrums, incoherent babbling and baby talk, a form of expression which he retained in adulthood. His chosen form of amusement was hurling heavy household objects at the heads of servants. Thaw spent his childhood bouncing among private schools in Pittsburgh, never doing well and described by teachers as a troublemaker. One teacher at the Wooster Prep School described Thaw, then aged 16, as having an "erratic kind of zig-zag" walk, "which seemed to involuntarily mimic his brain patterns." Thaw was granted admission to the University of Pittsburgh, where he was to study law, though he apparently did little studying. After a few years, he used his name and social status to transfer to Harvard College.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 191–192</ref>

Thaw later bragged that he had studied poker at Harvard. He reportedly lit cigars with hundred-dollar bills, went on long drinking binges, attended cockfights and spent much of his time romancing young women. In 1894, Thaw chased a cab driver down a street with a shotgun, believing he had been cheated out of ten cents change. He later claimed the shotgun was unloaded.<ref name="Uruburu189">Uruburu, p. 189</ref> Thaw was ultimately expelled from Harvard for "immoral practices," as well as intimidating and threatening students and teachers. His expulsion was immediate; he was given three hours to pack up and move out of the premises.<ref>Uruburu, p. 258</ref>

Thaw's father, in an attempt to curb his son's excesses, limited his monthly allowance to $2,500. This was a great deal of money in an era when lower-class workers earned $500 a year and a lavish dinner at Delmonico's restaurant cost $1.50. After the 1893 death of Thaw's father, who left his 22-year-old son $3 million (Template:Inflation) in his will,<ref name=obit /> Thaw's mother increased the monthly allowance to $8,000 (Template:Inflation), enabling him to indulge his every whim. Thaw was the beneficiary of this monthly income for the next eighteen years. He was heir to a fortune estimated at some $40 million.<ref name="Uruburu189"/>

Early on and for years into the future, Thaw's mother and a cadre of lawyers dedicated themselves to shielding him from any public scandal that would dishonor the family name. Monetary pay-offs became the customary method of assuring silence. One notorious example occurred in Thaw's hotel room in London, where he purportedly devised a lure for an unsuspecting bellboy, whom Thaw proceeded to restrain naked in a bathtub, brutalizing him with beatings from a riding crop. Thaw paid $5,000 to keep the incident quiet.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 209–210</ref>

With an enormous amount of cash at his disposal, and reserves of energy to match, Thaw repeatedly tore through Europe at a frenetic pace, frequenting bordellos where he subjected his partners to sadistic sex acts. In Paris in 1895, Thaw threw an extravagant party, reputedly costing $50,000 (Template:Inflation), which drew wide publicity. The attendees were Thaw himself and twenty-five of the most beautiful showgirls and prostitutes he could assemble. A military band was hired to provide musical entertainment. At the end of the meal, each of Thaw's guests was given a $1,000 piece of jewelry wrapped around the stem of a liqueur glass, served as the dessert course.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 190–191</ref>

Exhibiting the classic characteristics of a skilled, manipulative sociopath, Thaw kept the more sinister side of his personality in check when it suited his purposes. He had the ability, when required, to impress upon others that he was a gentle, caring soul. The term "playboy" entered the popular vernacular, reportedly inspired by Thaw himself.<ref name="Uruburu193"/>

Obsession with Stanford White

After his expulsion from Harvard, Thaw's sphere of activity alternated between Pittsburgh and New York City. In New York, he was determined to place himself amongst those privileged to occupy the summit of social prominence. His applications for membership in the city's elite men's clubs—the Metropolitan Club, the Century Club, the Knickerbocker Club and the Players' Club—were all rejected. His membership in the Union League Club was summarily revoked when he rode a horse up the steps into the club's entrance way, a "behavior unbefitting a gentleman."Template:Cn All of these snubs, Thaw was convinced, were directly or indirectly due to the intervention of the city's social lion, the architect Stanford White. His exclusion from clubs became part of a long line of perceived indignities heaped on Thaw, who maintained the unshakable certainty that his victimization was all orchestrated by White.<ref name="Uruburu180182">Uruburu, pp. 180–182</ref>

Another incident furthered Thaw's paranoid obsession with White. A disgruntled showgirl whom Thaw had publicly snubbed got her revenge by sabotaging a lavish party he had planned by hijacking all the female invitees and transplanting their festivities to White's infamous Tower Room at Madison Square Garden. Thaw, stubbornly ignorant of the real cause of the chain of events, once again blamed White for single-handedly destroying his revelries. His social humiliation was completed when glaring absence of "doe-eyed girlies" was reported in the press.<ref name="Uruburu180182"/>

The reality was that Thaw both admired and resented White's social stature. More significantly, he recognized that he and White shared a passion for similar lifestyles. White, unlike Thaw, could carry on without censure, and seemingly with impunity.<ref>Uruburu, p. 274</ref>

Drug use

Various sources document Thaw's drug addiction, which became habitual after his expulsion from Harvard. He reportedly injected large amounts of cocaine and morphine, occasionally mixing the two drugs into one injection. He was also known to use laudanum (tincture of opium), and on at least one occasion he drank a full bottle in a single swallow.<ref>Template:Cite newsTemplate:Dead linkTemplate:Cbignore</ref> Thaw's drug addiction was verified by his wife, Evelyn Nesbit. In a sworn statement she made before their marriage, she said that "One day...I found a little silver box oblong in shape, about two-and-one-half inches in length, containing a hypodermic syringe ... I asked Thaw what it was for, and he stated to me that he had been ill, and had to make some excuse. He said he had been compelled to take cocaine."<ref>Template:Cite web Deposition dated October 27, 1903, presented as State's evidence at murder trial of Harry Kendall Thaw, 1906.</ref>

Evelyn Nesbit

Relationship

Thaw had been in the audience of The Wild Rose, a show in which Nesbit, a popular artist's model and chorus girl about 17 years old, was a featured player. The smitten Thaw attended some forty performances over the better part of a year. Through an intermediary, he ultimately arranged a meeting with Nesbit, introducing himself as "Mr. Munroe". Even in their first personal encounter, Thaw revealed he was already extremely concerned about WhiteTemplate:Snd suddenly bringing him up in the conversation and warning her to stay away from him. Nesbit and her mother were, at the time, living in an apartment suite arranged by White, who was acting as Nesbit's benefactor and had conducted a sexual affair with her (despite being married with children and about three times her age). Nesbit found Thaw overly infatuated and recoiled from his attentions. He then visited her mother the next day and revealed his true identity to her. She was shocked, having read of his wealth and his antics in the newspapers of Pittsburgh, but she did not immediately tell her daughter about the visit. About a week later he arranged to sit near Nesbit at a restaurant, and after the dinner he announced to her with self-important bravado, "I am not Munroe...I am Henry Kendall Thaw, of Pittsburgh!"<ref name=Uruburu182188>Uruburu, pp. 182–188</ref> She too recognized his name from her Pittsburgh background, but she found his behavior bewildering and bordering on comical at the time.<ref name=Uruburu182188/>

Later, White and Nesbit's mother moved Nesbit to a boarding school in upstate New York in November 1902, where both White and Thaw visited often, with Thaw bearing gifts and praise, managing to impress both Nesbit's mother and the headmistress at the school. She was partly sent there to separate her from her recent romantic relationship with John Barrymore, who at the time was an irresponsible struggling artist who both her mother and White thought unsuitable as a potential husband, although he was a member of a prominent family and had proposed to her. Not long after their affair was cut off by the intervention, Barrymore would begin his rise to fame and fortune as a major acting star in theater and film.

While staying at the boarding school, Nesbit developed acute appendicitis in January 1903 when Thaw happened to be there for a visit. Nesbit underwent an emergency appendectomy arranged with the help of White and Thaw. While she was recuperating, Thaw suggested a European trip, convincing Nesbit and her mother that it would hasten Nesbit's recovery from the surgery. However, the trip they took a few months later proved to be anything but recuperative. Thaw's usual hectic mode of travel escalated into a non-stop itinerary, calculated to weaken Nesbit's emotional resilience, compound her physical frailty, and unnerve and exhaust her mother. As tensions mounted, mother and daughter began to argue, leading to Mrs. Nesbit's insistence on returning to the U.S. Having effectively alienated Nesbit from her mother, Thaw then took her to Paris, leaving Mrs. Nesbit in London.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 212–213</ref>

In Paris, Thaw continued to press Nesbit to become his wife; she again refused. Aware of Thaw's obsession with female chastity, she could not in good conscience accept his marriage proposal without revealing to him the truth of her relationship with White. What transpired next, according to Nesbit, was a marathon session of inquisition, during which time Thaw demanded every detail of the night when Nesbit lost her virginity to White. She would later testify that White had plied her with champagne and then raped her while she was unconscious. Throughout the grueling ordeal and questioning, Nesbit was tearful and hysterical; Thaw by turns was agitated and gratified by her responses. He further aggravated the wedge between mother and daughter, condemning Mrs. Nesbit as an unfit parent. Nesbit blamed the outcome of events on her own willful defiance of her mother's cautionary advice and defended her mother as naïve and unwitting.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 216–218</ref>

Thaw and Nesbit continued to travel around Europe. Thaw, as guide, took Nesbit on a tour of sites devoted to the cult of virgin martyrdom. In Domrémy, France, the birthplace of Joan of Arc, Thaw left an inscription in the visitor's book, writing "she would not have been a virgin if Stanford White had been around."<ref>Uruburu, p. 221</ref>

Thaw took Nesbit to Katzenstein Castle in Austria-Hungary, a forbidding, gothic structure sitting near a high mountaintop. He segregated the three servants in residence—a butler, cook and maid—in one end of the castle, from himself and Nesbit in the opposite end.<ref>Template:Cite web (Affidavit: Evelyn Nesbit vs. Harry K. Thaw) Template:Dead link The affidavit was introduced at the close of the state's case in the Harry Thaw murder trial.</ref> Nesbit later said she was locked in her room by Thaw, whose persona took on a dimension she had never before seen. Manic and violent, he allegedly beat her with a whip and sexually assaulted her over a two-week period. After his reign of terror had been expended, he was apologetic, and incongruously, after what had just transpired, was in an upbeat mood.<ref>Uruburu, p. 225</ref>

Marriage

Thaw had pursued Nesbit obsessively for nearly four years, continuously pressing her for marriage. Craving financial stability in her life, and in doing so denying that Thaw had only a tenuous grasp on reality, Nesbit finally consented to become his wife. They were wed on April 4, 1905. Thaw himself chose the wedding dress. Eschewing the traditional white gown, he dressed her in a black traveling suit decorated with brown trim.<ref>Uruburu, p. 255</ref>

The couple took up residence in the Thaw family mansion in Pittsburgh. In later years Nesbit took measure of life in the Thaw household; the Thaws were anything but intellectuals, and their value system was shallow and self-serving, "the plane of materialism which finds joy in the little things that do not matter—the appearance of ...[things]".<ref>Uruburu, p. 256</ref>

Envisioning a life of travel and entertainment, Nesbit was rudely awakened to a reality markedly different; a household ruled over by the sanctimonious propriety of "Mother Thaw". Thaw himself entered into his mother's sphere of influence, seemingly without protest, taking on the pose of pious son and husband. It was at this time that Thaw instituted a zealous campaign to expose White, corresponding with the reformer Anthony Comstock, an infamous crusader for moral probity and the expulsion of vice. Because of this activity, Thaw became convinced that he was being stalked by members of the notorious Monk Eastman Gang, hired by White to kill him. Thaw started to carry a gun. Nesbit later corroborated his mind-set: "[Thaw] imagined his life was in danger because of the work he was doing in connection with the vigilance societies and the exposures he had made to those societies of the happenings in White's flat."<ref>Uruburu, pp. 260–261</ref>

The killing of Stanford White

It is conjectured that White was unaware of Thaw's long-standing vendetta against him. White considered Thaw a poseur of little consequence, categorized him as a clown, and most tellingly, called him the "Pennsylvania pug"—a reference to Thaw's baby-faced features.<ref>Uruburu, p. 181</ref>

On June 25, 1906, Thaw and Nesbit were stopping in New York briefly before boarding a luxury liner bound for a European holiday.<ref>Uruburu, p. 270</ref> Thaw had purchased tickets for himself, his wife and two of his male friends for the show Mam'zelle Champagne, playing on the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden. Despite suffocating heat, which did not abate as night fell, Thaw inappropriately wore over his tuxedo a long black overcoat, which he refused to take off throughout the evening.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 272, 280</ref>

At 11:00Template:Nbspp.m., as the show was coming to a close, White appeared, taking his place at the table that was customarily reserved for him.<ref>Uruburu, p. 279</ref> Thaw had been agitated all evening, and abruptly bounced back and forth from his own table throughout the performance. Spotting White's arrival, he tentatively approached him several times, each time withdrawing in hesitation. During the finale, "I Could Love a Million Girls", Thaw produced a pistol and, standing some two feet from his target, fired three shots at White, killing him instantly. Part of White's blood-covered face was torn away and the rest of his features were unrecognizable, blackened by gunpowder.<ref name=thaw>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name="Uruburu282">Uruburu, p. 282</ref> Thaw remained standing over White's body, displaying the gun aloft in the air, resoundingly proclaiming, according to witness reports, "I did it because he ruined my wife! He had it coming to him! He took advantage of the girl and then abandoned her!"<ref name="Uruburu282"/> (The key witness allowed that he wasn't completely sure he heard Thaw correctly—that he might have said "he ruined my life" rather than "he ruined my wife".)<ref name="Uruburu282"/>

The crowd initially suspected the shooting might be part of the show, as elaborate practical jokes were popular in high society at the time. Soon, however, it became apparent that White was dead. Thaw, still brandishing the gun high above his head, walked through the crowd and met Nesbit at the elevator. When she asked what he had done, Thaw purportedly replied, "It's all right, I probably saved your life."<ref name=duke>Duke, Thomas Samuel, Celebrated Criminal Cases of the America, James H. Barry Co., 1910. pp. 647–851. Retrieved: July 28. 2012</ref>

Trial

Thaw was charged with first-degree murder and denied bail. A newspaper photo shows Thaw in The Tombs prison seated at a formal table setting, dining on a meal catered for him by Delmonico's restaurant. In the background is further evidence of the preferential treatment provided to him. Conspicuously absent is the standard issue jail cell cot; during his confinement Thaw slept in a brass bed. Exempted from wearing prisoner's garb, he was allowed to wear his own custom-tailored clothes. The jail's doctor was induced to allow Thaw a daily ration of champagne and wine.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 298, 300</ref> In his jail cell, it was reported that Thaw heard the heavenly voices of young girls calling to him, which he interpreted as a sign of divine approval. He was in a euphoric mood, unshakable in his belief that the public would applaud the man who had rid the world of the menace of Stanford White.<ref>Uruburu, p. 292</ref>

The "Trial of the Century"

As early as the morning following the shooting, news coverage became both chaotic and single-minded, and ground forward with unrelenting momentum. Any person, place or event, no matter how peripheral to the incident, was seized on by reporters and hyped as newsworthy copy. Facts were thin but sensationalist reportage was plentiful in this, the heyday of yellow journalism.<ref>"Mrs. Thaw Urged Her Husband On" The Washington Post (July 9, 1906); p. 1. From a statement allegedly made to police by Nesbit's former friend, actress Edna McClure</ref> The hard-boiled news reporters were bolstered by a contingent of counterparts, christened "Sob Sisters", whose stock-in-trade was the human interest piece, heavy on sentimental tropes and melodrama, crafted to pull on the emotions and punch them up to fever pitch.

The rampant interest in the White murder and its key players were used by both the defense and prosecution to feed malleable reporters any "scoops" that would give their respective sides an advantage in the public forum. Thaw's mother, as was her custom, primed her own publicity machine through monetary pay-offs. The district attorney's office took on the services of a Pittsburgh public relations firm, McChesney and Carson, backing a print smear campaign aimed at discrediting Thaw and Nesbit.<ref>Uruburu, p. 319</ref> Pittsburgh newspapers displayed lurid headlines, a sample of which blared, "Woman Whose Beauty Spelled Death and Ruin".<ref>Uruburu, p. 311</ref>

Defense strategy

The main issue in the case was the question of premeditation. At the outset, the formidable District Attorney, William Travers Jerome, preferred not to take the case to trial by having Thaw declared legally insane. This was to serve a two-fold purpose. The approach would save time and money, and of equal if not greater consideration, it would avoid the unfavorable publicity that would no doubt be generated from disclosures made during testimony on the witness stand—revelations that threatened to discredit many of high social standing. Thaw's first defense attorney, Lewis Delafield, concurred with the prosecutorial position, seeing that an insanity plea was the only way to avoid a death sentence for their client. Thaw dismissed Delafield, who he was convinced wanted to "railroad [him] to Matteawan as the half-crazy tool of a dissolute woman".<ref>Uruburu, p. 305</ref>

Thaw's mother, however, was adamant that her son not be stigmatized by clinical insanity. She pressed for the defense to follow a compromise strategy; one of temporary insanity, or what in that era was referred to as a "brainstorm". Acutely conscious of the insanity in her side of the family, and after years of protecting her son's hidden life, she feared her son's past would be dragged out into the open, ripe for public scrutiny. Protecting the Thaw family reputation had become nothing less than a vigilant crusade for Thaw's mother. She proceeded to hire a team of doctors, at a cost of half a million dollars, to substantiate that her son's act of murder constituted a single aberrant act.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 323–324</ref>

Possibly concocted by the yellow press in concert with Thaw's attorneys, the temporary insanity defense, in Thaw's case, was dramatized as a uniquely American phenomenon. Branded "dementia Americana", this catch phrase encompassed the male prerogative to revenge any woman whose sacred chastity had been violated. In essence, murder motivated by such a circumstance was the act of a man justifiably unbalanced.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

The two trials

Thaw was tried twice for the murder of White. Due to the unusual amount of publicity the case had received, it was ordered that the jury members be sequestered.<ref>Uruburu, p. 322</ref> The trial proceedings began on January 23, 1907, and the jury went into deliberation on April 11. After forty-seven hours, the twelve jurors emerged deadlocked. Seven had voted guilty, and five voted not guilty. Thaw was outraged that the trial had not vindicated the murder, that the jurors had not recognized it as the act of a chivalrous man defending innocent womanhood. He went into fits of physical flailing and crying when he considered the very real possibility that he would be labeled a madman and imprisoned in an asylum.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 312, 354</ref> The second trial took place from January 1908 through February 1, 1908.<ref>Uruburu, p. 358</ref>

At the second trial, Thaw pleaded temporary insanity.<ref>"Thaw lays killing to a "brainstorm" The New York Times (July 30, 1909)</ref> This legal strategy was developed by Thaw's new chief defense counsel, Martin W. Littleton, whom Thaw and his mother had retained for $25,000 (Template:Inflation).<ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref> Thaw was found not guilty by reason of insanity and sentenced to incarceration for life at the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Fishkill, New York. His wealth allowed him to arrange accommodations for his comfort and be granted privileges not given to the general Matteawan population.

Nesbit had testified at both trials. It is conjectured that the Thaws promised her a comfortable financial future if she provided testimony favorable to Thaw's case. It was a conditional agreement; if the outcome proved negative, she would receive nothing. The rumored amount of money the Thaws pledged for her cooperation ranged from $25,000 to $1 million.<ref>Uruburu, p. 324</ref> Throughout the prolonged court proceedings, Nesbit had received inconsistent financial support from the Thaws, made to her through their attorneys. After the close of the second trial, the Thaws virtually abandoned Nesbit, cutting off all funds.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 358–361</ref> However, in an interview Nesbit's grandson, Russell Thaw, gave to the Los Angeles Times in 2005, it was his belief that Nesbit received $25,000 from the family after the end of the second trial.<ref name=flee>Rasmussen, Cecilia. "Girl in Red Velvet Swing Longed to Flee Her Past" Los Angeles Times (December 11, 2005). Retrieved: August 18, 2012</ref> Nesbit and Thaw divorced in 1915.<ref>Uruburu, p. 368</ref>

Legal maneuvers: Push for freedom

Immediately after his commitment to Matteawan, Thaw marshaled the forces of a legal team charged with the mission of having him declared sane.<ref>Uruburu, p. 359</ref> The legal process was protracted.

In July 1909, Thaw's lawyers attempted to have their client released on a writ of habeas corpus. Two key witnesses for the state gave testimony at the hearing detrimental to the defense. Landlady Susan "Susie" Merrill recounted a chronology of Thaw's activities during the period of 1902 through 1905, in which he rented apartments at two separate locations from Merrill, brought girls into the premises, and physically and emotionally abused them. Newspaper reports speculated on an item brought into evidence by Merrill, a "jeweled whip" which graphically suggested the scenarios played out in Thaw's rooms. Money was paid to keep the women silent. A Thaw attorney, Clifford Hartridge, corroborated Merrill's story, identifying himself as the intermediary who handled the monetary payoffs, some $30,000, between Merrill, the various women and Thaw. On August 12, 1910, the court dismissed the petition and Thaw was returned to Matteawan. The presiding judge wrote: "...the petitioner would be dangerous to public safety and was afflicted with chronic delusion insanity."<ref name=duke />

Determined to escape confinement, on 19 August 1913, Thaw walked out of Matteawan Asylum for the Criminally Insane and was driven over the Canadian border near Coaticook, Quebec where he was promptly arrested and taken to jail in Sherbrooke.<ref name=":0">Template:Cite book</ref> He was in Canada for around 3 weeks by having his lawyers file writs of habeas corpus, before being deported back the US in Vermont.<ref name=":0" /> His escape was aided by at least five men, including ex-New York Assemblyman Richard J. Butler.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> It is believed Thaw's mother, who had years of practice extricating her son from dire situations, orchestrated and financed her son's escape. His attorney, William Lewis Shurtleff, fought extradition to the U.S.; among Shurtleff's legal team was future Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent.<ref name="St. Laurent">Template:Cite news</ref> Thaw was taken to Mt. Madison House in Gorham, New Hampshire, for the summer and kept under the watch of Sheriff Holman Drew, but in December 1914 he was extradited to New York and was able to secure a trial to establish whether he should still be considered insane. On July 16, 1915, the jury determined Thaw to be no longer insane and set him free.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name="newyorkcity100yearsago.blogspot.com">"February 10, 1910 – Harry K. Thaw appeals to the Supreme Court". New York City 100 Years Ago BlogSpot website. Retrieved: July 13, 2012</ref>

Throughout the two murder trials, as well as after Thaw's escape from Matteawan, a contingent of the public, seduced by the resulting exaggeration of the press, had become defenders of what they deemed Thaw's justifiable murder of White. Letters were written in support of Thaw, lauding him as a defender of "American womanhood". Sheet music was published for a musical piece titled: "For My Wife and Home".<ref name=flee /> Soon after Thaw's release, The Sun, in July 1915, weighed in with its own estimation of the justice system in the Thaw matter: "In all this nauseous business, we don't know which makes the gorge rise more, the pervert buying his way out, or the perverted idiots that hail him with huzzas."<ref>Uruburu, p. 357</ref>

After Thaw's escape from Matteawan, Nesbit had expressed her own feelings about her husband's most recent imbroglio: "He hid behind my skirts through two trials and I won't stand for it again. I won't let lawyers throw any more mud at me."<ref>"Murder of the Century"Template:Dead linkTemplate:Cbignore American Experience, Retrieved: July 27, 2012</ref>

Arrest for assault

In 1916, Thaw was charged with the kidnapping, beating, and sexual assault of nineteen-year-old Frederick Gump of Kansas City, Missouri. His acquaintance with Gump dated to December 1915, and Thaw had worked to gain the trust of the Gump family. Thaw had enticed Gump to come to New York under the pretense of underwriting the teenager's enrollment at Carnegie Institute, and reserved rooms for him at the Hotel McAlpin. The New York Times later reported that, upon his arrival, Gump was confronted by "Thaw, armed with a short, stocky whip rushing for him." After the assault, Thaw fled to Philadelphia with the police in pursuit. When apprehended, he was found to have attempted suicide by slashing his throat.

Initially, Thaw tried to bribe the Gump family, offering to pay them a half million dollars if they would drop all criminal charges against him. Ultimately, he was arrested, jailed and tried. Found insane, he was confined to Kirkbride Asylum in Philadelphia, where he was held under tight security.<ref name=obit/><ref name="newyorkcity100yearsago.blogspot.com"/><ref>"Old Print Articles: Harry K. Thaw And Evelyn Nesbit, After Stanford White's Murder, New York Times (1917, 1926)" Afflictor.com website. Retrieved: July 13, 2012</ref> He was ultimately judged sane and regained his freedom in April 1924. Thaw's obituary, printed in the Times the day after his death in 1947, implies that Thaw's mother and the Gump family arrived at a monetary settlement.<ref name=obit />

Children

Evelyn Nesbit gave birth to a son, Russell William Thaw, on October 25, 1910, in Berlin. Nesbit always maintained he was Thaw's biological child, conceived during a conjugal visit to Thaw while he was confined at Matteawan. Thaw, throughout his life, denied paternity.<ref>Uruburu, pp. 360, 363</ref>

Later life

In 1924, Thaw purchased a historic home, known as Kenilworth, in Clearbrook, Virginia. While living there, he ingratiated himself with the locals, joined the Rouss Fire Company, and even marched in a few local parades in his fireman's uniform. He was regarded as an eccentric by the citizens of Clearbrook, but does not seem to have run into a great deal of additional legal trouble while living there. In 1926, he published a book of memoirs titled The Traitor, written to vindicate his murder of White. Thaw never regretted what he had done. Twenty years after taking White's life, he said: "Under the same circumstances, I'd kill him tomorrow."<ref name=obit />

During the late 1920s, Thaw went into the film production business, based on Long Island in New York. His initial plan was to make short comedies and stories about bogus spiritualists. In 1927, he contracted with John S. Lopez and detective-story author Arthur B. Reeve for a batch of scenarios focused on the theme of fraudulent spiritualism. This association generated a lawsuit against Thaw, who refused to pay his collaborators for the script work they had done. Thaw, rejecting the original concept, now conceived of a project to film the story of his own life. He asserted, therefore, the original agreement was no longer valid and he had no financial obligation to his partners. Ultimately, in 1935, a legal judgment ruled in Lopez's favor in the amount of $35,000.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Death

Thaw died of a heart attack in Miami, Florida, on February 22, 1947, ten days after his 76th birthday.<ref name=obit>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite magazine</ref> At his death Thaw left an estate with an estimated value of $1 million (equivalent to $Template:Inflation million as of Template:Inflation-year).<ref name="dollartimes.com">DollarTimes.com, Accessed June 1, 2018</ref> In his will, he left Nesbit a bequest of $10,000 ($Template:Inflation,000 as of Template:Inflation-year),<ref name="dollartimes.com"/> about 1% of his net worth.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> He was buried in Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

References

Notes Template:Reflist

Bibliography

- Baatz, Simon, The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century (New York: Little, Brown, 2018) {{ISBN|978-0316396653}}

- Uruburu, Paula, American Eve: Evelyn Nesbit, Stanford White: The Birth of the "It" Girl and the Crime of the Century. New York: Riverhead Books, 2008 Template:ISBN

Further reading

- Collins, Frederick L. Glamorous Sinners (1932).

- Geary, Rick. Madison Square Tragedy: The Murder of Stanford White (2011).

- Langford, Gerald. The Murder of Stanford White (2011).

- Lessard, Suzannah. The Architect of Desire: Beauty and Danger in the Stanford White Family (1997).

- Mooney, Michael Macdonald. Evelyn Nesbit and Stanford White: Love and Death in the Gilded Age (1976).

- Samuels, Charles. The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing (1953).

- Thaw, Evelyn Nesbit. The Story of My Life (1914).

- Thaw, Evelyn Nesbit. Prodigal Days (1934).

- Thaw, Harry K. The Traitor (1926).

- Vatsal, Radha. No. 10 Doyers Street (2025).

External links

- Template:Internet Archive author

- Harry Kendall Thaw and trial at Flickr Commons

- "Harry Thaw's trial" Scans of a dinner program with Jurists autographs

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article on family

- 1871 births

- 1947 deaths

- American rapists

- Burials at Allegheny Cemetery

- 20th-century American trials

- 20th-century American murderers

- American prisoners and detainees

- Harvard College alumni

- American people acquitted of murder

- People acquitted by reason of insanity

- People from Pittsburgh

- Thaw family

- University of Pittsburgh people

- Prisoners and detainees of New York (state)

- Trials in New York (state)

- Vigilantism against sex offenders in the United States