Offside (association football)

Template:Short description Template:For Template:Use British English Template:Use dmy dates

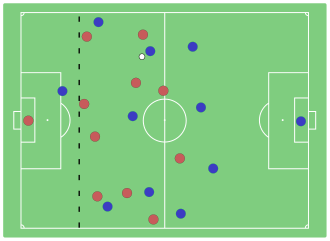

Offside is one of the laws in association football, codified in Law 11 of the Laws of the Game. The law states that a player is in an offside position if any of their body parts, except the hands and arms, are in the opponents' half of the pitch and closer to the opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second-last opponent (the last opponent is usually, but not necessarily, the goalkeeper).<ref name="laws2017-law11">Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Being in an offside position is not an offence in itself, but a player so positioned when the ball is played by a teammate can be judged guilty of an offside offence if they receive the ball or will otherwise become "involved in active play", will "interfere with an opponent", or will "gain an advantage" by being in that position. Offside is often considered one of the most difficult-to-understand aspects of the sport.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Significance

Offside is judged at the moment the ball is last touched by the most recent teammate to touch the ball. Being in an offside position is not an offence in itself. A player who was in an offside position at the moment the ball was last touched or played by a teammate must then become involved in active play, in the opinion of the referee, in order for an offence to occur. When the offside offence occurs, the referee stops play, and awards an indirect free kick to the defending team from the place where the offending player became involved in active play.<ref name="laws2017-law11"/>

The offside offence is neither a foul nor misconduct as it does not belong to Law 12. Like fouls, however, any play (such as the scoring of a goal) that occurs after an offence has taken place, but before the referee is able to stop the play, is nullified.<ref name="laws2017-law10">Template:Cite webTemplate:Dead link</ref> The only time an offence related to offside is cautionable is if a defender deliberately leaves the field in order to deceive their opponents regarding a player's offside position, or if a forward, having left the field, returns and gains an advantage. In neither of these cases is the player penalised for being offside; instead they are cautioned for acts of unsporting behaviour.<ref name="laws2017-law11"/>

An attacker who is able to receive the ball behind the opposition defenders is often in a good position to score. The offside rule limits attackers' ability to do this, requiring that they be onside when the ball is played forward. Though restricted, well-timed passes and fast running allow an attacker to move into such a situation after the ball is kicked forward without committing the offence. Officiating decisions regarding offside, which can often be a matter of only centimetres or inches, can be critical in games, as they may determine whether a promising attack can continue, or even if a goal is allowed to stand.

One of the main duties of the assistant referees is to assist the referee in adjudicating offside<ref name="laws2017-law6">Template:Cite webTemplate:Dead link</ref>—their position on the sidelines giving a more useful view sideways across the pitch. Assistant referees communicate that an offside offence has occurred by raising a signal flag.<ref name="laws2017-PGMO">Template:Cite webTemplate:Dead link</ref>Template:Rp However, as with all officiating decisions in the game, adjudicating offside is ultimately up to the referee, who can overrule the advice of their assistants if they see fit.<ref name="laws2017-law5">Template:Cite webTemplate:Dead link</ref>

Application

The application of the offside rule may be considered in three steps: offside position, offside offence, and offside sanction.

Offside position

A player is in an "offside position" if they are in the opposing team's half of the field and also "nearer to the opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second-last opponent."<ref name="laws2017-law11"/> The 2005 edition of the Laws of the Game included a new IFAB decision that stated, "In the definition of offside position, 'nearer to his opponents' goal line' means that any part of their head, body or feet is nearer to their opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second last opponent. The arms are not included in this definition".<ref name=2005-changes>Template:Cite web</ref> By 2017, the wording had changed to say that, in judging offside position, "The hands and arms of all players, including the goalkeepers, are not considered."<ref name="laws2017-law11"/> In other words, a player is in an offside position if two conditions are met:

- Any part of the player's head, body or feet is in the opponents' half of the field (excluding the half-way line).

- Any part of the player's head, body or feet is closer to the opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second-last opponent.<ref name="laws2017-law11"/>

The goalkeeper counts as an opponent in the second condition, but it is not necessary that the last opponent be the goalkeeper.

Offside offence

A player in an offside position at the moment the ball is touched or played by a teammate is only penalised for committing an offside offence if, in the opinion of the referee, they become involved in active play by:

- Interfering with play

- "playing or touching the ball passed or touched by a team-mate"<ref name="laws2017-law11"/>

- Interfering with an opponent

- "preventing an opponent from playing or being able to play the ball by clearly obstructing the opponent's line of vision or

- challenging an opponent for the ball or

- clearly attempting to play a ball which is close to them when this action impacts on an opponent or

- making an obvious action which clearly impacts on the ability of an opponent to play the ball"<ref name="laws2017-law11"/>

- Gaining an advantage by playing the ball or interfering with an opponent when it has

- "- rebounded or been deflected off the goalpost, crossbar, match official or an opponent

- – been deliberately saved by any opponent"<ref name="laws2017-law11"/>

In addition to the above criteria, in the 2017–18 edition of the Laws of the Game, the IFAB made a further clarification that, "In situations where a player moving from, or standing in, an offside position is in the way of an opponent and interferes with the movement of the opponent towards the ball this is an offside offence if it impacts on the ability of the opponent to play or challenge for the ball."<ref name="laws2017-law11"/>

There is no offside offence if a player receives the ball directly from a goal kick, a corner kick, or a throw-in. It is also not an offence if the ball was last deliberately played by an opponent (except for a deliberate save). In this context, according to the IFAB, "A 'save' is when a player stops, or attempts to stop, a ball which is going into or very close to the goal with any part of the body except the hands/arms (unless the goalkeeper within the penalty area)."<ref name="laws2017-law11"/>

An offside offence may occur if a player receives the ball directly from either a direct free kick, indirect free kick or dropped-ball.

Since offside is judged at the time the ball is touched or played by a teammate, not when the player receives the ball, it is possible for a player to receive the ball significantly past the second-to-last opponent, or even the last opponent, without committing an offence, since an onside player is free to run to any position after the ball is played.

A player who was offside when their teammate played the ball (and therefore liable for an offside offence should they interfere with play) but becomes onside when the ball is played by another player then ceases to be liable for an offside offence. That is, the determination of offside is reset each time the ball is played by a different onside player.

Determining whether a player is "involved in active play" can be complex. The quote, "If he's not interfering with play, what's he doing on the pitch?" has been attributed to Bill Nicholson<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and Danny Blanchflower.<ref>Template:Cite AV media</ref> In an effort to avoid such criticisms, which were based on the fact that phrases such as "interfering with play", "interfering with an opponent", and "gaining an advantage" were not clearly defined, FIFA issued new guidelines for interpreting the offside law in 2003; and these were incorporated into Law 11 in July 2005.<ref name="2005-changes"/> The new wording sought to define the three cases more precisely, but a number of football associations and confederations continued to request more information about what movements a player in an offside position could make without interfering with an opponent. In response to these requests, IFAB circular 3 was issued in 2015 to provide additional guidance on the criteria for interfering with an opponent. This additional guidance is now included in the main body of the law, and forms the last three conditions under the heading "Interfering with an opponent" as shown above. The circular also contained additional guidance on the meaning of a save, in the context of a ball that has "been deliberately saved by any opponent."<ref>Template:Cite webTemplate:Dead link</ref>

Offside sanction

The sanction for an offside offence is an indirect free kick for the opponent at the place where the offence occurred, even if it is in the player's own half of the field of play.<ref name="laws2017-law11"/>

Officiating

In enforcing this rule, the referee depends greatly on an assistant referee, who generally keeps in line with the second-to-last opponent, the ball, or the halfway line, whichever is closer to the goal line of their relevant end.<ref name="laws2017-PGMO"/>Template:Rp An assistant referee signals for an offside offence by first raising their flag to a vertical position and then, if the referee stops play, by partly lowering their flag to an angle that signifies the location of the offence:<ref name="laws2017-PGMO"/>Template:Rp

- Flag pointed at a 45-degree angle downwards: offence has occurred in the third of the pitch nearest to the assistant referee;<ref name="laws2017-law6"/>Template:Rp

- Flag parallel to the ground: offence has occurred in the middle third of the pitch;<ref name="laws2017-law6"/>Template:Rp

- Flag pointed at a 45-degree angle upwards: offence has occurred in the third of the pitch furthest from the assistant referee.<ref name="laws2017-law6"/>Template:Rp

The assistant referees' task with regard to offside can be difficult, as they need to keep up with attacks and counter-attacks, consider which players are in an offside position when the ball is played, and then determine whether and when the offside-positioned players become involved in active play. The risk of false judgement is further increased by the foreshortening effect, which occurs when the distance between the attacking player and the assistant referee is significantly different from the distance to the defending player, and the assistant referee is not directly in line with the defender. The difficulty of offside officiating is often underestimated by spectators. Trying to judge if a player is level with an opponent at the moment the ball is kicked is not easy: if an attacker and a defender are running in opposite directions, they can be two metres (6') apart in less than a second.

Some researchers believe that offside officiating errors are "optically inevitable".<ref>Template:Citation</ref> It has been argued that human beings and technological media are incapable of accurately detecting an offside position quickly enough to make a timely decision.<ref>Template:Citation</ref> Sometimes it simply is not possible to keep all the relevant players in the visual field at once.<ref>Template:Cite journal Correction: Template:Citation</ref> There have been some proposals for automated enforcement of the offside rule.<ref>Template:Citation</ref>

VAR and semi-automation

In matches using Video Assistant Referees (VAR) assistant referees who decide on offsides are required to avoid raising the flag for an offside decision until the play proceeds to a natural conclusion, unless the offside is obvious. This allows a team who might have been called for an offside offence to instead continue and any subsequent goal to be checked by VAR.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Beginning in the mid-2020s, Semi-Automated Offside Technology (SAOT) began to be used at high-level games. SAOT systems use multiple high-speed cameras to determine the positions of players at the moment the ball is kicked, assisting the VAR in making speedy offside decisions. SAOT produces 3D virtual replays of the situation which are displayed on stadium screens and broadcasts.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Motivation

The motivations for offside rules varied at different times, and were not always clearly stated when the rules were changed.

According to the anonymous author of a November 1863 newspaper article in the Sporting Gazette, "For a player to place himself nearer his opponent's goal than the ball, and to wait for it to be kicked to him, is not anywhere recognised but as being decidedly unfair".<ref>Template:Cite journal; emphasis added.</ref> Curry and Dunning suggest that offside play was considered "highly ungentlemanly" at some schools; this attitude may have been reflected in the use of terminology such as "sneaking" at Eton and "loiter[ing]" at Cambridge.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref><ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

In general, offside rules intend to prevent players from "goal-hanging"–staying near the opponent's goal and waiting for the ball to be passed to them directly. This was considered to be unsportsmanlike and made the game boring. In contrast, the offside rules force players not to get ahead of the ball, and thus favour dribbling the ball and short passes over few long passes.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

History

Before 1863

Traditional games

A law similar to offside was used in the game of hurling to goals played in Cornwall in the early 17th century:<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Quote

School and university football

Offside laws are found in the largely uncodified and informal football games played at English public schools in the early 19th century. An 1832 article discussing the Eton wall game complained of "[t]he interminable multiplicity of rules about sneaking, picking up, throwing, rolling, in straight, with a vast number more", using the term "sneaking" to refer to Eton's offside law.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The novel Tom Brown's School Days, published in 1857 but based on the author's experiences at Rugby School from 1834 to 1842, discussed that school's offside law:<ref>Template:Cite book [emphasis added]</ref> Template:Quote

The first published set of laws of any code of football (Rugby School, 1845), stated that "[a] player is off his side if the ball has touched one of his own side behind him, until the other side touch it." Such a player was prevented from kicking the ball, touching the ball down, or interfering with an opponent.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

Many other school and university laws from this period were similar to Rugby School's in that they were "strict"—i.e. any player ahead of the ball was in an off-side position.<ref name=Carosi>Template:Cite web</ref> (This is similar to the current offside law in rugby, under which any player between the ball and the opponent's goal who takes part in play, is liable to be penalised.)<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Such laws included Shrewsbury School (1855),<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> Uppingham School (1857),<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> Trinity College, Hartford (1858),<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> Winchester College (1863),<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> and the Cambridge Rules of 1863.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

Some school and university rules provided an exception to this general pattern. In the 1847 laws of the Eton Field Game, a player could not be considered "sneaking" if there were four or more opponents between him and the opponents' goal line.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> A similar "rule of four" was found in the 1856 Cambridge Rules<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> and the rules of Charterhouse School (1863).<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

Club football

Most surviving rules of independent football clubs from before 1860 lack any offside law. This is true of the brief handwritten set of laws for the Foot-Ball Club of Edinburgh (1833),<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> the published laws of Surrey Football Club (1849),<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> the first set of laws of Sheffield Football Club (1858)<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> and those of Melbourne Football Club (1859).<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> In the Sheffield game, players known as "kick-throughs" were positioned permanently near the opponents' goal.<ref name=Carosi/>

In the early 1860s, this began to change. In 1861, Forest FC adopted a set of laws based on the 1856 Cambridge Rules, with its "rule of four".<ref>Template:Citation. From the context, it is clear that "the Cambridge Rules" is intended to refer to the Cambridge Rules of 1856.</ref> The 1862 laws of Barnes FC featured a strict offside law.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> Sheffield FC adopted a weak offside law at the beginning of the 1863–64 season.<ref>In a letter to The Field in February 1867, Sheffield FC secretary Harry Chambers wrote that Sheffield FC had adopted a rule at the beginning of the 1863 season requiring one opponent to be level or closer to the opponent's goal. See Template:Cite journal This claim is confirmed by a letter from secretary William Chesterman to the FA in 1863: see Template:Cite news</ref>

J. C. Thring

J. C. Thring was an advocate for the strictest possible offside law. A resident master at Uppingham School from 1859 to 1864, Thring criticised most existing offside laws for being too lax. The Rugby laws, for example, were at fault because they permitted an offside player to rejoin play immediately after an opponent touched the ball,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> while Eton's rule of four allowed "an immense amount of sneaking" when the number of players was unlimited.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Thring expressed his views through correspondence in the sporting newspapers such as The Field, and through the publication in 1862 of The Simplest Game, a proposed set of laws of football. In The Simplest Game, Thring included a strict offside law which required a player in an offside position ("out of play", in Thring's terminology) to "return behind the ball as soon as possible".<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

The influence of Thring's views is evidenced by the adoption of his proposed offside law from The Simplest Game in the first draft of the FA laws (see below).

The F. A. laws of 1863

On 17 November 1863, the newly formed Football Association adopted a resolution mirroring Thring's law from the Simplest Game:<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> Template:Quote This text was reflected in the first draft of laws drawn up by FA secretary Ebenezer Morley.

On 24 November, Morley presented his draft laws to the FA for final approval.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> That meeting was, however, disrupted by a dispute over the subject of "hacking" (allowing players to carry the ball, provided they could be kicked in the shins by opponents when doing so, in the manner of Rugby School). The opponents of hacking brought the delegates' attention to the Cambridge Rules of 1863 (which banned carrying and hacking):<ref name="nov_24">Template:Cite news</ref> Discussion of the Cambridge rules, and suggestions for possible communication with Cambridge on the subject, served to delay the final "settlement" of the laws to a further meeting, on 1 December. A number of representatives who supported rugby-style football did not attend this additional meeting,<ref>Harvey (2005), pp. 144–145</ref> resulting in hacking and carrying being banned.<ref name="dec_1">Template:Cite news</ref>

Although the offside law was not itself a significant issue in the dispute between the pro- and anti-hacking clubs, it was completely rewritten. The original law, taken from Thring's Simplest Game, was replaced by a modified version of the equivalent law from the Cambridge Rules:<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>Template:Quote The law adopted by the FA was "strict"—i.e., it penalised any player in front of the ball.<ref name=Carosi/> There was one exception for the "kick from behind the goal line" (the 1863 laws' equivalent of a goal kick). This exception was necessary because every player on the attacking side would have otherwise been "out of play" from such a kick.

Subsequent developments: offside position

Three-player rule (1866)

At the first revision of the FA laws, in February 1866, an important qualifier was added to soften the "strict" offside law:<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> Template:Quote

At the FA's meeting, the alteration "gave rise to a lengthy discussion, many thinking with Mr Morley that it would be better to do away with the off side [law] altogether, especially as the Sheffield clubs had none. It being found, however, that the rule could not be expunged without notice, the alteration was passed."<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name=Carosi/><ref name="4Drules">Template:Cite web</ref>

Contemporaneous reports do not indicate the reason for the change.<ref>For example, Template:Cite journal</ref> Charles Alcock, writing in 1890, suggested that it was made in order to induce two public schools, Westminster and Charterhouse, to join the association.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>According to Template:Cite book, Alcock made a claim that the change "secured the co-operation of Westminster and Charterhouse Schools" in Football Annual, 1870, p. 38</ref> Those two schools did indeed become members of the FA after the next annual FA meeting (February 1867), in response to a letter-writing campaign by newly installed FA secretary Robert Graham.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>The exact date on which the two schools joined the F.A. is uncertain. Both were members as of 1 January 1868 (see Graham op. cit.). Charterhouse was still using its own rules as of 5 October 1867. Westminster had "adopted the rules of the association" by 19 October 1867, though Routledge's Handbook of Football was still advertised as containing the "rules of the game as played at Westminster" in November 1867; see Template:Cite journal and Template:Cite journal</ref>

Early proposals for change (1867–1874)

Over the next seven years, there were several attempts to change the three-player rule, but none was successful:

- In 1867, Barnes FC proposed that the offside rule should be removed altogether, arguing that "a player did not stop to count whether there were three of his opponents between him and their own goal".<ref name="fa_meeting_1867">Template:Cite journal</ref>

- It was also proposed that the FA should revert to its original "strict" offside rule. This change was introduced in 1868 (Branham College), 1871 ("The Oxford Association") and 1872 (Notts County).<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- There were attempts to introduce the one-player rule of the Sheffield Football Association in 1867 (Sheffield FC), 1872 (Sheffield Football Association), 1873 (Nottingham Forest), and 1874 (Sheffield Association).<ref name="fa_meeting_1867"/>

Offside was the subject of the biggest dispute between the Sheffield Football Association (which produced its own "Sheffield Rules") and the Football Association.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> However, the two codes were eventually unified without any change in this area; the Sheffield Clubs accepted the FA's three-player offside rule in 1877, after the FA compromised by allowing the throw-in to be taken in any direction.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Offside in own half (1907)

The original laws allowed players to be in an offside position even when in their own half. This happened rarely, but was possible when one team pressed high up the field, for example in a Sunderland v Wolverhampton Wanderers match in December 1901.<ref name="pickford"/><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> When an attacking team adopted the so-called "one back" game, in which only the goalkeeper and one outfield player remained in defensive positions, it was even possible for players to be caught offside in their own penalty area.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

In May 1905, Clyde FC suggested that players should not be offside in their own half, but this suggestion was rejected by the Scottish Football Association.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>Template:Cbignore It was objected that the change would lead to "forwards hanging about close to the half-way line, as opportunists".<ref name=pickford>Template:Cite journal</ref> After the Scotland v England international of April 1906 ended with the Scottish wingers being repeatedly caught offside by England's use of a "one back" game,<ref>Wilson (2013), p. 37</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Clyde again proposed the same rule-change to the Scottish FA meeting: this time it was accepted.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

The Scottish proposal gained support in England.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> At the 1906 meeting of the International Football Association Board, the Scottish FA announced that it would introduce the proposed change at the next annual meeting, in 1907.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In March 1907, the council of the [English] Football Association approved this change,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> and it was passed by IFAB in June 1907.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

Two-player rule (1925)

The Scottish FA urged the change from a three-player to a two-player offside rule as early as 1893.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Such a change was first proposed at a meeting of IFAB in 1894, where it was rejected.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> It was proposed again by the SFA in 1902, upon the urging of Celtic FC, and again rejected.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> A further proposal from the SFA also failed in 1913, after the Football Association objected.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The SFA advanced the same proposal in 1914, when it was again rejected after opposition from both the Football Association and the Football Association of Wales.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Meetings of the International Board were suspended after 1914 because of the First World War. After they resumed in 1920, the SFA once again proposed the two-player rule in 1922, 1923, and 1924. In 1922 and 1923, the Scottish Association withdrew its proposal after English FA opposed it.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> In 1924, the Scottish proposal was once again opposed by the English FA, and defeated;<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> it was, however, indicated that a version of the proposal would be adopted the next year.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

On 30 March 1925, the FA arranged a trial match at Highbury where two proposed changes to the offside rules were tested. During the first half, a player could not be offside unless within forty yards of the opponents' goal-line. In the second half, the two-player rule was used.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

The two-player proposal was considered by the FA at its annual meeting on 8 June. Proponents cited the new rule's potential to reduce stoppages, avoid refereeing errors, and improve the spectacle, while opponents complained that it would give "undue advantage to attackers"; referees were overwhelmingly opposed to the change. The two-player rule was nevertheless approved by the FA by a large majority.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> At IFAB's meeting later that month, the two-player rule finally became part of the Laws of the Game.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

The two-player rule was one of the more significant rule changes in the history of the game during the 20th century. It led to an immediate change in the style of play, with the game becoming more stretched, "short passing giv[ing] way to longer balls", and the development of the W-M formation.<ref>Wilson (2013), p. 20</ref> It also led to an increase in goalscoring: 4,700 goals were scored in 1,848 Football League games in 1924–25. This number rose to 6,373 goals (from the same number of games) in 1925–26.<ref name=Carosi/>

Attacker level with second-last defender (1990)

In 1990, IFAB declared that an attacker level with the second-last defender is onside, whereas previously such a player had been considered offside. This change, proposed by the Scottish FA, was made in order to "encourage the attacking team" by "giving the attacking player an advantage over the defender".<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Parts of body (2005)

In 2005, IFAB clarified that, when evaluating an attacking player's position for the purposes of the offside law, the part of the player's head, body or feet closest to the defending team's goal-line should be considered, with the hands and arms being excluded because "there is no advantage to be gained if only the arms are in advance of the opponent".<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In 2016, it was further clarified that this principle should apply to all players, both attackers and defenders, including the goalkeeper.<ref name="offside_2016_changes">Template:Cite web</ref>

Defender outside the field of play (2009)

In 2009, it was stated that a defender who leaves the field of play without the referee's permission must be considered to be on the nearest boundary line for the purposes of deciding whether an attacker is in an offside position.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Halfway line (2016)

In 2016, it was clarified that a player on the halfway line itself cannot be in an offside position: part of the player's head, body or feet must be within the opponent's half of the field of play in order to be considered offside.<ref name="offside_2016_changes"/>

Unadopted experiments

During the 1973–74 and 1974–75 seasons, an experimental version of the offside rule was operated in the Scottish League Cup and Drybrough Cup competitions.<ref name = "scottish experiment">Template:Cite web</ref> The concept was that offside should only apply in the last Template:Convert of play (inside or beside the penalty area).<ref name = "scottish experiment"/> To signify this, the horizontal line of the penalty area was extended to the touchlines.<ref name = "scottish experiment"/> FIFA President Sir Stanley Rous attended the 1973 Scottish League Cup Final, which was played using these rules.<ref name = "scottish experiment"/> The manager of one of the teams involved, Celtic manager Jock Stein, complained that it was unfair to expect teams to play under one set of rules in one game and then a different set a few days before or later.<ref name = "scottish experiment"/> The experiment was quietly dropped after the 1974–75 season, as no proposal for a further experiment or rule change was submitted for the Scottish Football Association board to consider.<ref name = "scottish experiment"/> It was briefly experimented again in the 1991 FIFA U-17 World Championship, in Italy.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In 1972, the North American Soccer League adopted a variation of the offside rule in which it added a line on the field 35 yards from each goal line; a player could only be offside within that area of the opponent's half. The rule was dropped in 1982 at the insistence of FIFA which threatened to withdraw recognition of the league if it did not apply all of the official rules of football.<ref>The history of the North American Soccer League</ref>

Subsequent developments: exceptions at the restart of play

Goal kick

Since the first FA laws of 1863, a player has not been penalised for being in an offside position at the moment a teammate takes a goal kick.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> (According to the "strict" offside law used in 1863, every player on the attacking side would automatically have been in an offside position from such a goalkick, since it had to be taken from the goal line and a player could be in an offside position even when in their own half.)<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

Throw-in

Under the original laws of 1863, it was not possible to be offside from a throw-in;<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> however, since the ball was required to be thrown in at right-angles to the touch-line, it would have been unusual for a player to gain significant advantage from being ahead of the ball.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

In 1877, the throw-in law was changed to allow the ball to be thrown in any direction.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> The next year (1878) a new law was introduced to allow a player to be offside from a throw-in.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

This situation lasted until 1920, when the law was altered to prevent a player being offside from a throw-in.<ref>Template:Cite webTemplate:Dead link</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref> This rule-change was praised on the grounds that it would deter teams from "seeking safety or wasting time by sending [the ball] into touch", and thus reduce stoppages.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Corner kick

When first introduced in 1872, the corner kick was required to be taken from the corner-flag itself, which made it impossible for an attacking player to be in an offside position relative to the ball.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> In 1874, the corner-kick was allowed to be taken up to one yard from the corner-flag, thus opening up the possibility of a player being in an offside position.<ref>Template:Cite wikisource</ref> At the International Football Conference of December 1882, it was agreed that a player should not be offside from a corner-kick; this change was incorporated into the Laws of the Game in 1883.<ref name="laws_1883">Template:Cite wikisource</ref>

Free kick

The laws of football have always permitted an offside offence to be committed from a free kick. The free kick contrasts, in this respect, with other restarts of play such as the goal kick, corner kick, and throw-in.

A 1920 proposal by the FA to exempt the free-kick from the offside rule was unexpectedly rejected by IFAB.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> A further unsuccessful proposal to remove the possibility of being offside from a direct free-kick was rejected in 1929.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Similar proposals to prevent offside offences from any free-kick were advanced in 1974 and 1986, each time without success.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In 1987, the Football Association (FA) obtained the permission of IFAB to test such a rule in the 1987–88 GM Vauxhall Conference.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref> At the next annual meeting, the FA reported to IFAB that the experiment had, as predicted, "assisted further the non-offending team and also generated more action near goal, resulting in greater excitement for players and spectators"; it nevertheless withdrew the proposal.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Offside trap

Pioneered in the early 20th century by Notts County<ref>Template:Citation</ref> and later adopted by influential Argentine coach Osvaldo Zubeldía,<ref>Template:Citation</ref> the offside trap is a defensive tactic designed to force the attacking team into an offside position. Just before an attacking player is played a through ball, the last defender or defenders move upfield, isolating the attacker into an offside position. The execution requires careful timing by the defence and is considered a risk, since running upfield against the direction of attack may leave the goal exposed.<ref name=":0">Template:Cite web</ref> Now that it changes to the interpretations of "interfering with play, interfering with an opponent and gaining an advantage", it means a player is not guilty of an offside offence unless they become directly and clearly involved in active play, and players not involved in active play cannot be "caught offside", making the tactic riskier. An attacker, upon realising they are in an offside position, may simply choose to avoid interfering with play until the ball is played by someone else.

Manager Arrigo Sacchi was also known for using a high defensive line, with distance between the defence and midfield lines never greater than 25 to 30 metres (yards), and the offside trap with his teams. He introduced a more attacking–minded tactical philosophy with A.C. Milan, which was highly successful, namely an aggressive high-pressing system, which used a 4–4–2 formation, an attractive, fast, attacking, and possession-based playing style, and which also used innovative elements such as zonal marking and a high back–line line playing the offside trap, which largely deviated from previous systems in Italian football, despite still maintaining defensive solidity.<ref name="The greatest teams of all time: AC Milan 1988-90">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="SacchitakeoverParma">Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Liverpool F.C. under Jürgen Klopp, a noted follower of Sacchi, were known for their highly effective offside trap. It involved playing a high defensive line with quick centre-backs like Virgil van Dijk and Ibrahima Konaté who could move forward quickly to catch opponents offside.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In the 2021–22 Premier League season, they caught 53% more the amount of opponents offside than the next best team (144 times compared to Manchester City's 94).<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Not all offside traps need to have a high line, the offside trap can be executed from everywhere on the pitch. Manuel Pellegrini often used the offside trap with the defenders sitting at the edge of their own box. The positioning of the defensive line dictates the available space that the opponents can run into. By adopting a high line, the opposition sometimes may be crammed into their own half, while a lower defensive line gives less space to run in behind.<ref name=":0" />

Citations

General and cited references

External links

- Laws of the Game 2021 - Offside

- FIFA Offside Presentation, June 2005

- The Offside Trap in Football Explained - Simple Football

- FIFA interactive guide

- Professional Referee Organization offside discussion, from 2015 pre-season (includes video examples)