Old Church Slavonic

Template:Short description Template:Redirect {{#invoke:Infobox|infobox}}Template:Template otherTemplate:Main other{{#invoke:Check for unknown parameters|check |unknown=Template:Main other |preview=Page using Template:Infobox language with unknown parameter "_VALUE_"|ignoreblank=y| acceptance | agency | aiatsis | aiatsis2 | aiatsis3 | aiatsis4 | aiatsis5 | aiatsis6 | aiatsisname | aiatsisname2 | aiatsisname3 | aiatsisname4 | aiatsisname5 | aiatsisname6 | altname | ancestor | ancestor2 | ancestor3 | ancestor4 | ancestor5 | ancestor6 | ancestor7 | ancestor8 | ancestor9 | ancestor10 | ancestor11 | ancestor12 | ancestor13 | ancestor14 | ancestor15 | boxsize | coordinates | coords | created | creator | date | dateprefix | development_body | dia1 | dia2 | dia3 | dia4 | dia5 | dia6 | dia7 | dia8 | dia9 | dia10 | dia11 | dia12 | dia13 | dia14 | dia15 | dia16 | dia17 | dia18 | dia19 | dia20 | dia21 | dia22 | dia23 | dia24 | dia25 | dia26 | dia27 | dia28 | dia29 | dia30 | dia31 | dia32 | dia33 | dia34 | dia35 | dia36 | dia37 | dia38 | dia39 | dia40 | dialect_label | dialects | ELP | ELP2 | ELP3 | ELP4 | ELP5 | ELP6 | ELPname | ELPname2 | ELPname3 | ELPname4 | ELPname5 | ELPname6 | era | ethnicity | extinct | fam1 | fam2 | fam3 | fam4 | fam5 | fam6 | fam7 | fam8 | fam9 | fam10 | fam11 | fam12 | fam13 | fam14 | fam15 | family | familycolor | fontcolor | glotto | glotto2 | glotto3 | glotto4 | glotto5 | glottoname | glottoname2 | glottoname3 | glottoname4 | glottoname5 | glottopedia | glottorefname | glottorefname2 | glottorefname3 | glottorefname4 | glottorefname5 | guthrie | ietf | image | imagealt | imagecaption | imagescale | iso1 | iso1comment | iso2 | iso2b | iso2comment | iso2t | iso3 | iso3comment | iso6 | isoexception | lc1 | lc2 | lc3 | lc4 | lc5 | lc6 | lc7 | lc8 | lc9 | lc10 | lc11 | lc12 | lc13 | lc14 | lc15 | lc16 | lc17 | lc18 | lc19 | lc20 | lc21 | lc22 | lc23 | lc24 | lc25 | lc26 | lc27 | lc28 | lc29 | lc30 | lc31 | lc32 | lc33 | lc34 | lc35 | lc36 | lc37 | lc38 | lc39 | lc40 | ld1 | ld2 | ld3 | ld4 | ld5 | ld6 | ld7 | ld8 | ld9 | ld10 | ld11 | ld12 | ld13 | ld14 | ld15 | ld16 | ld17 | ld18 | ld19 | ld20 | ld21 | ld22 | ld23 | ld24 | ld25 | ld26 | ld27 | ld28 | ld29 | ld30 | ld31 | ld32 | ld33 | ld34 | ld35 | ld36 | ld37 | ld38 | ld39 | ld40 | linglist | linglist2 | linglist3 | linglist4 | linglist5 | linglist6 | lingname | lingname2 | lingname3 | lingname4 | lingname5 | lingname6 | lingua | lingua2 | lingua3 | lingua4 | lingua5 | lingua6 | lingua7 | lingua8 | lingua9 | lingua10 | linguaname | linguaname2 | linguaname3 | linguaname4 | linguaname5 | linguaname6 | linguaname7 | linguaname8 | linguaname9 | linguaname10 | listclass | liststyle | map | map2 | mapalt | mapalt2 | mapcaption | mapcaption2 | mapscale | minority | module | name | nation | nativename | notice | notice2 | official | posteriori | pronunciation | protoname | pushpin_image | pushpin_label | pushpin_label_position | pushpin_map | pushpin_map_alt | pushpin_map_caption | pushpin_mapsize | qid | ref | refname | region | revived | revived-cat | revived-category | script | setting | sign | signers | speakers | speakers_label | speakers2 | stand1 | stand2 | stand3 | stand4 | stand5 | stand6 | standards | state | states }}<templatestyles src="Template:Infobox/styles-images.css" />

Old Church Slavonic (OCS) or Old Slavonic (Template:IPAc-en Template:Respell)<ref name= "lpd">Template:Citation</ref>Template:Efn is the first Slavic literary language and the oldest extant written Slavonic language attested in literary sources. It belongs to the South Slavic subgroup of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family and remains the liturgical language of many Christian Orthodox churches.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and undertaking the task of translating the Gospels and necessary liturgical books into it<ref name=Catholic_Encyclopedia>Template:Cite encyclopedia</ref> as part of the Christianization of the Slavs.Template:Sfnp<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> It is thought to have been based primarily on the dialect of the 9th-century Byzantine Slavs living in the Province of Thessalonica (in present-day Greece).

Old Church Slavonic played an important role in the history of the Slavic languages and served as a basis and model for later Church Slavonic traditions. Some Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches use these Church Slavonic recensions as a liturgical language to this day.

As the oldest attested Slavic language, Old Church Slavonic provides important evidence for the features of Proto-Slavic, the reconstructed common ancestor of all Slavic languages.

Nomenclature

The name of the language in Old Church Slavonic texts was simply Slavic (Template:Lang, Template:Lang),<ref name="nandris">Template:Harvp.</ref> derived from the word for Slavs (Template:Lang, Template:Lang), the self-designation of the compilers of the texts. This name is preserved in the modern native names of the Slovak and Slovene languages. The terms Slavic and Slavonic are interchangeable in English. The language is sometimes called Old Slavic, which may be confused with the distinct Proto-Slavic language. Bulgarian, Croatian, Macedonian, Serbian, Slovene and Slovak linguists have claimed Old Church Slavonic; thus OCS has also been variously called Old Bulgarian, Old Macedonian, Old Slovenian, Old Croatian, or Old Serbian, or even Old Slovak.Template:Sfnp The commonly accepted terms in modern English-language Slavic studies are Old Church Slavonic and Old Church Slavic.

The term Old Bulgarian<ref>Ziffer, Giorgio – On the Historicity of Old Church Slavonic UDK 811.163.1(091) Template:Webarchive</ref> (Template:Langx, Template:Langx) is the designation used by most Bulgarian-language writers. It was used in numerous 19th-century sources, e.g. by August Schleicher, Martin Hattala, Leopold Geitler and August Leskien,<ref>A. Leskien, Handbuch der altbulgarischen (altkirchenslavischen) Sprache, 6. Aufl., Heidelberg 1922.</ref><ref>A. Leskien, Grammatik der altbulgarischen (altkirchenslavischen) Sprache, 2.-3. Aufl., Heidelberg 1919.</ref><ref name="usa">"American contributions to the Tenth International Congress of Slavists", Sofia, September 1988, Alexander M. Schenker, Slavica, 1988, Template:ISBN, pp. 46–47.</ref> who noted similarities between the first literary Slavic works and the modern Bulgarian language. For similar reasons, Russian linguist Aleksandr Vostokov used the term Slav-Bulgarian. The term is still used by some writers but nowadays normally avoided in favor of Old Church Slavonic.

The term Old Macedonian<ref>J P Mallory, D Q Adams. Encyclopaedia of Indo-European Culture. Pg 301 "Old Church Slavonic, the liturgical language of the Eastern Orthodox Church, is based on the Thessalonican dialect of Old Macedonian, one of the South Slavic languages."</ref><ref>R. E. Asher, J. M. Y. Simpson. The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, Introduction "Macedonian is descended from the dialects of Slavic speakers who settled in the Balkan peninsula during the 6th and 7th centuries CE. The oldest attested Slavic language, Old Church Slavonic, was based on dialects spoken around Salonica, in what is today Greek Macedonia. As it came to be defined in the 19th century, geographic Macedonia is the region bounded by Mount Olympus, the Pindus range, Mount Shar and Osogovo, the western Rhodopes, the lower course of the river Mesta (Greek Nestos), and the Aegean Sea. Many languages are spoken in the region but it is the Slavic dialects to which the glossonym Macedonian is applied."</ref><ref>R. E. Asher, J. M. Y. Simpson. The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, History, "Modern Macedonian literary activity began in the early 19th century among intellectuals attempt to write their Slavic vernacular instead of Church Slavonic. Two centers of Balkan Slavic literary arose, one in what is now northeastern Bulgaria, the other in what is now southwestern Macedonia. In the early 19th century, all these intellectuals called their language Bulgarian, but a struggled emerged between those who favored northeastern Bulgarian dialects and those who favored western Macedonian dialects as the basis for what would become the standard language. Northeastern Bulgarian became the basis of standard Bulgarian, and Macedonian intellectuals began to work for a separate Macedonian literary language. "</ref><ref>Tschizewskij, Dmitrij (2000) [1971]. Comparative History of Slavic Literatures. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press. Template:ISBN. "The brothers knew the Old Bulgarian or Old Macedonian dialect spoken around Thessalonica."</ref><ref>Benjamin W. Fortson. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, pg. 431 "Macedonian was not distinguished from Bulgarian for most of its history. Constantine and Methodius came from Macedonian Thessaloniki; their old Bulgarian is therefore at the same time 'Old Macedonian'. No Macedonian literature dates from earlier than the nineteenth century, when a nationalist movement came to the fore and a literacy language was established, first written with Greek letters, then in Cyrillic"</ref><ref>Benjamin W. Fortson. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, p. 427 "The Old Church Slavonic of Bulgaria, regarded as something of a standard, is often called Old Bulgarian (or Old Macedonian)"</ref><ref>Henry R. Cooper. Slavic Scriptures: The Formation of the Church Slavonic Version of the Holy Bible, p. 86 "We do not know what portions of the Bible in Church Slavonic, let alone a full one, were available in Macedonia by Clement's death. And although we might wish to make Clement and Naum patron saints of such as glagolitic-script, Macedonian-recension Church Slavonic Bible, their precise contributions to it we will have to take largely on faith."</ref> is occasionally used by Western scholars in a regional context. According to Slavist Henrik Birnbaum, the term was introduced mostly by Macedonian scholars and it is anachronistic because there was no separate Macedonian language, distinguished from early Bulgarian, in the 9th century.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

The obsolete<ref name="books.google.com">Template:Cite book</ref> term Old Slovenian<ref name= "books.google.com"/><ref name= "gray">Template:Harvp.</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref name= "Kamusella 2008"/> was used by early 19th-century scholars who conjectured that the language was based on the dialect of Pannonia.

History

It is generally held that the language was standardized by two Byzantine missionaries, Cyril and his brother Methodius, for a mission to Great Moravia (the territory of today's eastern Czech Republic and western Slovakia; for details, see Glagolitic alphabet).Template:Sfnp The mission took place in response to a request by Great Moravia's ruler, Duke Rastislav for the development of Slavonic liturgy.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

As part of preparations for the mission, in 862/863, the missionaries developed the Glagolitic alphabet and translated the most important prayers and liturgical books, including the Aprakos Evangeliar, the Psalter, and the Acts of the Apostles, allegedly basing the language on the Slavic dialect spoken in the hinterland of their hometown, Thessaloniki,Template:Efn in present-day Greece.

Based on a number of archaicisms preserved until the early 20th century (the articulation of yat as Template:IPAslink in Boboshticë, Drenovë, around Thessaloniki, Razlog, the Rhodopes and Thrace and of yery as Template:IPAslink around Castoria and the Rhodopes, the presence of decomposed nasalisms around Castoria and Thessaloniki, etc.), the dialect is posited to have been part of a macrodialect extending from the Adriatic to the Black Sea, and covering southern Albania, northern Greece and the southernmost parts of Bulgaria.Template:Sfnp

Because of the very short time between Rastislav's request and the actual mission, it has been widely suggested that both the Glagolitic alphabet and the translations had been "in the works" for some time, probably for a planned mission to Bulgaria.Template:Sfnp<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

The language and the Glagolitic alphabet, as taught at the Great Moravian Academy (Template:Langx), were used for government and religious documents and books in Great Moravia between 863 and 885. The texts written during this phase contain characteristics of the West Slavic vernaculars in Great Moravia.

In 885, Pope Stephen V prohibited the use of Old Church Slavonic in Great Moravia in favour of Latin.Template:Sfnp King Svatopluk I of Great Moravia expelled the Byzantine missionary contingent in 886.

Exiled students of the two apostles then brought the Glagolitic alphabet to the Bulgarian Empire, being at least some of them Bulgarians themselves.<ref>Kiril Petkov, The Voices of Medieval Bulgaria, Seventh-Fifteenth Century: The Records of a Bygone Culture, Volume 5, BRILL, 2008, Template:ISBN, p. 161.</ref><ref>("This great father of ours and light of Bulgaria was by origin of the European Moesians whom the people commonly known as Bulgarians…"-Kosev, Dimitŭr; et al. (1969), Documents and Materials on the History of the Bulgarian People, Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, p. 54)</ref><ref>(The Voices of Medieval Bulgaria, Seventh-Fifteenth Century, East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450-1450, Kiril Petkov, BRILL, 2008, ISBN 9047433750, p. 153.)</ref> Boris I of Bulgaria (Template:Reign) received and officially accepted them; he established the Preslav Literary School and the Ohrid Literary School.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Both schools originally used the Glagolitic alphabet, though the Cyrillic script developed early on at the Preslav Literary School, where it superseded Glagolitic as official in Bulgaria in 893.Template:Sfnp<ref>Silent Communication: Graffiti from the Monastery of Ravna, Bulgaria. Studien Dokumentationen. Mitteilungen der ANISA. Verein für die Erforschung und Erhaltung der Altertümer, im speziellen der Felsbilder in den österreichischen Alpen (Verein ANISA: Grömbing, 1996) 17. Jahrgang/Heft 1, 57–78.</ref><ref>"The scriptorium of the Ravna monastery: once again on the decoration of the Old Bulgarian manuscripts 9th–10th c." In: Medieval Christian Europe: East and West. Traditions, Values, Communications. Eds. Gjuzelev, V. and Miltenova, A. (Sofia: Gutenberg Publishing House, 2002), 719–26 (with K. Popkonstantinov).</ref><ref>Popkonstantinov, Kazimir, "Die Inschriften des Felsklosters Murfatlar". In: Die slawischen Sprachen 10, 1986, S. 77–106.</ref>

The texts written during this era exhibit certain linguistic features of the vernaculars of the First Bulgarian Empire. Old Church Slavonic spread to other South-Eastern, Central, and Eastern European Slavic territories, most notably Croatia, Serbia, Bohemia, Lesser Poland, and principalities of the Kievan Rus' – while retaining characteristically Eastern South Slavic linguistic features.

Later texts written in each of those territories began to take on characteristics of the local Slavic vernaculars, and by the mid-11th century Old Church Slavonic had diversified into a number of regional varieties (known as recensions). These local varieties are collectively known as the Church Slavonic language.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Apart from use in the Slavic countries, Old Church Slavonic served as a liturgical language in the Romanian Orthodox Church, and also as a literary and official language of the princedoms of Wallachia and Moldavia (see Old Church Slavonic in Romania), before gradually being replaced by Romanian during the 16th to 17th centuries.

Church Slavonic maintained a prestigious status, particularly in Russia, for many centuriesTemplate:Spaced ndashamong Slavs in the East it had a status analogous to that of Latin in Western Europe, but had the advantage of being substantially less divergent from the vernacular tongues of average parishioners.

Some Orthodox churches, such as the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox Church, Serbian Orthodox Church, Ukrainian Orthodox Church and Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric, as well as several Eastern Catholic Churches, still use Church Slavonic in their services and chants.<ref>Тодорова-Гергова, Светлана. Отец Траян Горанов: За богослужението на съвременен български език, Българско национално радио ″Христо Ботев″, 1 април 2021 г.</ref>

Scripts

Initially Old Church Slavonic was written with the Glagolitic alphabet, but later Glagolitic was replaced by Cyrillic,<ref>Template:Harvp.</ref> which was developed in the First Bulgarian Empire by a decree of Boris I of Bulgaria in the 9th century. Of the Old Church Slavonic canon, about two-thirds is written in Glagolitic.

The local Serbian Cyrillic alphabet was preserved in Serbia, Bosnia and parts of Croatia, while a variant of the angular Glagolitic alphabet was preserved in Croatia. See Early Cyrillic alphabet for a detailed description of the script and information about the sounds it originally expressed.

Phonology

For Old Church Slavonic, the following segments are reconstructible.<ref name="Huntley 1993 126–7">Template:Harvp.</ref> A few sounds are given in Slavic transliterated form rather than in IPA, as the exact realisation is uncertain and often differs depending on the area that a text originated from.

Consonants

For English equivalents and narrow transcriptions of sounds, see Help:IPA/Old_Church_Slavonic.

- Template:Note These phonemes were written and articulated differently in different recensions: as Template:Font (Template:IPAslink) and Template:Font (Template:IPAslink) in the Moravian recension, Template:Font (Template:IPAslink) and Template:Font (Template:IPAslink) in the Bohemian recension, Template:Font/Template:Font (also spelled Template:Font/Template:Font, Template:IPA) and Template:Font/Template:Font (Template:IPA) in the Bulgarian recension(s). In Serbia, Template:Font was used to denote both sounds. The abundance of Middle Ages toponyms featuring Template:IPA and Template:IPA in North Macedonia, Kosovo and the Torlak-speaking parts of Serbia indicates that at the time, the clusters were articulated as Template:IPA & Template:IPA as well, even though current reflexes are different.Template:Sfnp

- Template:Note Template:IPA appears mostly in early texts, becoming Template:IPA later on.

- Template:NoteThe distinction between Template:IPA, Template:IPA, and Template:IPA, on one hand, and palatal Template:IPA, Template:IPA, and Template:IPA, on the other, is not always indicated in writing. When it is, it is shown by a palatalization diacritic over the letter: ⟨ л҄ ⟩ ⟨ н҄ ⟩ ⟨ р҄ ⟩. Also, palatalization could be indicated by using iotified vowel letters (⟨ ꙗ, ѥ, ю, ѩ, ѭ ⟩) after consonants: Template:Lang 'will (n.), freedom'.

- Template:Ref Template:IPA and Template:IPA are thought to have been originally pronounced as palatalized consonants: Template:IPA, Template:IPA, as evident from following vowels (ъ>ь, o>e) and from occasional use of ⟨ ꙗ ⟩ after ⟨ ꙃ ⟩ in inscriptions.

- Template:Ref The sound Template:IPA, which came from the second and progressive palatalizations of Proto-Slavic Template:IPA, was usually not distinguished in writing from Template:IPA, but its existence is inferred from spellings such as Template:Lang (also spelled Template:Lang and Template:Lang) 'any(one), every(one)'.

Vowels

For English equivalents and narrow transcriptions of sounds, see Old Church Slavonic Pronunciation on Wiktionary.

- Accent is not indicated in writing and must be inferred from later languages and from reconstructions of Proto-Slavic.

- Template:Note All front vowels were iotated word-initially and succeeding other vowels. The same sometimes applied for *a and *ǫ. In the Bulgarian region, an epenthetic *v was inserted before *ǫ in the place of iotation.

- Template:Note The distinction between /i/, /ji/, and /jɪ/ is rarely indicated in writing and must be inferred from reconstructions of Proto-Slavic. In Glagolitic, the three are written as ⟨Template:Lang⟩, ⟨Template:Lang⟩, and ⟨Template:Lang⟩ respectively. In Cyrillic, /jɪ/ may sometimes be written as ⟨Template:Lang⟩, and /ji/ as ⟨Template:Lang⟩, although this is rarely the case.

- Template:Note Yers preceding *j became tense, this was inconsistently reflected in writing in the case of *ь (ex: чаꙗньѥ or чаꙗние, both pronounced [t͡ʃɑjɑn̪ije]), but never with *ъ (which was always written as a yery).

- Template:Note Yery was the descendant of Proto-Balto-Slavic long *ū and was a high back unrounded vowel. Tense *ъ merged with *y, which gave rise to yery's spelling as ⟨Template:Lang⟩ (later ⟨Template:Lang⟩, modern ⟨Template:Lang⟩).

- Template:Note The yer vowels ь and ъ (ĭ and ŭ) are often called "ultrashort" and were lower, more centralised and shorter than their tense counterparts *i and *y. Both yers had a strong and a weak variant, with a yer always being strong if the next vowel is another yer. Weak yers disappeared in most positions in the word, already sporadically in the earliest texts but more frequently later on. Strong yers, on the other hand, merged with other vowels, particularly ĭ with e and ŭ with o, but differently in different areas.

- Template:Note The pronunciation of yat (ѣ/ě) differed by area. In Bulgaria it was a relatively open vowel, commonly reconstructed as Template:IPA, but further north its pronunciation was more closed and it eventually became a diphthong Template:IPA (e.g. in modern standard Bosnian, Croatian, and Montenegrin, or modern standard Serbian spoken in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as in Czech — the source of the grapheme ě) or even Template:IPA in many areas (e.g. in Chakavian Croatian, Shtokavian Ikavian Croatian, and Bosnian dialects or Ukrainian) or Template:IPA (modern standard Serbian spoken in Serbia).

- Template:Note *a was the descendant of Proto-Slavic long *o and was a low back unrounded vowel. Its iotated variant was often confused with *ě (in Glagolitic they are even the same letter: Ⱑ), so *a was probably fronted to *ě when it followed palatal consonants (this is still the case in Rhodopean dialects).

- Template:Note The exact articulation of the nasal vowels is unclear because different areas tend to merge them with different vowels. ę /ɛ̃/ is occasionally seen to merge with e or ě in South Slavic, but becomes ja early on in East Slavic. ǫ /ɔ̃/ generally merges with u or o, but in Bulgaria, ǫ was apparently unrounded and eventually merged with ъ.

Phonotactics

Several notable constraints on the distribution of the phonemes can be identified, mostly resulting from the tendencies occurring within the Common Slavic period, such as intrasyllabic synharmony and the law of open syllables. For consonant and vowel clusters and sequences of a consonant and a vowel, the following constraints can be ascertained:<ref>Template:Harvp.</ref>

- Two adjacent consonants tend not to share identical features of manner of articulation

- No syllable ends in a consonant

- Every obstruent agrees in voicing with the following obstruent

- Velars do not occur before front vowels

- Phonetically palatalized consonants do not occur before certain back vowels

- The back vowels /y/ and /ъ/ as well as front vowels other than /i/ do not occur word-initially: the two back vowels take prothetic /v/ and the front vowels prothetic /j/. Initial /a/ may take either prothetic consonant or none at all.

- Vowel sequences are attested in only one lexeme (paǫčina 'spider's web') and in the suffixes /aa/ and /ěa/ of the imperfect

- At morpheme boundaries, the following vowel sequences occur: /ai/, /au/, /ao/, /oi/, /ou/, /oo/, /ěi/, /ěo/

Morphophonemic alternations

As a result of the first and the second Slavic palatalizations, velars alternate with dentals and palatals. In addition, as a result of a process usually termed iotation (or iodization), velars and dentals alternate with palatals in various inflected forms and in word formation.

| original | /k/ | /g/ | /x/ | /sk/ | /zg/ | /sx/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| first palatalization and iotation | /č/ | /ž/ | /š/ | /št/ | /žd/ | /š/ |

| second palatalization | /c/ | /dz/ | /s/ | /sc/, /st/ | /zd/ | /sc/ |

| original | /b/ | /p/ | /sp/ | /d/ | /zd/ | /t/ | /st/ | /z/ | /s/ | /l/ | /sl/ | /m/ | /n/ | /sn/ | /zn/ | /r/ | /tr/ | /dr/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iotation | /bl'/ | /pl'/ | /žd/ | /žd/ | /št/ | /št/ | /ž/ | /š/ | /l'/ | /šl'/ | /ml'/ | /n'/ | /šn'/ | /žn'/ | /r'/ | /štr'/ | /ždr'/ |

In some forms the alternations of /c/ with /č/ and of /dz/ with /ž/ occur, in which the corresponding velar is missing. The dental alternants of velars occur regularly before /ě/ and /i/ in the declension and in the imperative, and somewhat less regularly in various forms after /i/, /ę/, /ь/ and /rь/.<ref>Syllabic sonorant, written with jer in superscript, as opposed to the regular sequence of /r/ followed by a /ь/.</ref> The palatal alternants of velars occur before front vowels in all other environments, where dental alternants do not occur, as well as in various places in inflection and word formation described below.<ref name="Huntley">Template:Harvp.</ref>

As a result of earlier alternations between short and long vowels in roots in Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Balto-Slavic and Proto-Slavic times, and of the fronting of vowels after palatalized consonants, the following vowel alternations are attested in OCS: /ь/ : /i/; /ъ/ : /y/ : /u/; /e/ : /ě/ : /i/; /o/ : /a/; /o/ : /e/; /ě/ : /a/; /ъ/ : /ь/; /y/ : /i/; /ě/ : /i/; /y/ : /ę/.<ref name="Huntley" />

Vowel:∅ alternations sometimes occurred as a result of sporadic loss of weak yer, which later occurred in almost all Slavic dialects. The phonetic value of the corresponding vocalized strong jer is dialect-specific.

Grammar

Template:Main As an ancient Indo-European language, OCS has a highly inflective morphology. Inflected forms are divided in two groups, nominals and verbs. Nominals are further divided into nouns, adjectives and pronouns. Numerals inflect either as nouns or pronouns, with 1–4 showing gender agreement as well.

Nominals can be declined in three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), three numbers (singular, plural, dual) and seven cases: nominative, vocative, accusative, instrumental, dative, genitive, and locative. There are five basic inflectional classes for nouns: o/jo-stems, a/ja-stems, i-stems, u-stems, and consonant stems. Forms throughout the inflectional paradigm usually exhibit morphophonemic alternations.

Fronting of vowels after palatals and j yielded dual inflectional class o : jo and a : ja, whereas palatalizations affected stem as a synchronic process (N sg. vlьkъ, V sg. vlьče; L sg. vlьcě). Productive classes are o/jo-, a/ja-, and i-stems. Sample paradigms are given in the table below:

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gloss | Stem type | Nom | Voc | Acc | Gen | Loc | Dat | Instr | Nom/Voc/Acc | Gen/Loc | Dat/Instr | Nom/Voc | Acc | Gen | Loc | Dat | Instr |

| "city" | o m. | gradъ | grade | gradъ | grada | gradě | gradu | gradomь | grada | gradu | gradoma | gradi | grady | gradъ | graděxъ | gradomъ | grady |

| "knife" | jo m. | nožь | nožu | nožь | noža | noži | nožu | nožemь | noža | nožu | nožema | noži | nožę | nožь | nožixъ | nožemъ | noži |

| "wolf" | o m | vlьkъ | vlьče | vlьkъ | vlьka | vlьcě | vlьku | vlьkomь | vlьka | vlьku | vlьkoma | vlьci | vlьky | vlьkъ | vlьcěxъ | vlьkomъ | vlьky |

| "wine" | o n. | vino | vino | vino | vina | vině | vinu | vinomь | vině | vinu | vinoma | vina | vina | vinъ | viněxъ | vinomъ | viny |

| "field" | jo n. | poʎe | poʎe | poʎe | poʎa | poʎi | poʎu | poʎemь | poʎi | poʎu | poʎema | poʎa | poʎa | poʎь | poʎixъ | poʎemъ | poʎi |

| "woman" | a f. | žena | ženo | ženǫ | ženy | ženě | ženě | ženojǫ | ženě | ženu | ženama | ženy | ženy | ženъ | ženaxъ | ženamъ | ženami |

| "soul" | ja f. | duša | duše | dušǫ | dušę | duši | duši | dušejǫ | duši | dušu | dušama | dušę | dušę | dušь | dušaxъ | dušamъ | dušami |

| "hand" | a f. | rǫka | rǫko | rǫkǫ | rǫky | rǫcě | rǫcě | rǫkojǫ | rǫcě | rǫku | rǫkama | rǫky | rǫky | rǫkъ | rǫkaxъ | rǫkamъ | rǫkami |

| "bone" | i f. | kostь | kosti | kostь | kosti | kosti | kosti | kostьjǫ | kosti | kostьju | kostьma | kosti | kosti | kostьjь | kostьxъ | kostьmъ | kostьmi |

| "home" | u m. | domъ | domu | domъ/-a | domu | domu | domovi | domъmь | domy | domovu | domъma | domove | domy | domovъ | domъxъ | domъmъ | domъmi |

Adjectives are inflected as o/jo-stems (masculine and neuter) and a/ja-stems (feminine), in three genders. They could have short (indefinite) or long (definite) variants, the latter being formed by suffixing to the indefinite form the anaphoric third-person pronoun jь.

Synthetic verbal conjugation is expressed in present, aorist and imperfect tenses while perfect, pluperfect, future and conditional tenses/moods are made by combining auxiliary verbs with participles or synthetic tense forms. Sample conjugation for the verb vesti "to lead" (underlyingly ved-ti) is given in the table below.

| person/number | Present | Asigmatic (simple, root) aorist | Sigmatic (s-) aorist | New (ox) aorist | Imperfect | Imperative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 sg. | vedǫ | vedъ | věsъ | vedoxъ | veděaxъ | |

| 2 sg. | vedeši | vede | vede | vede | veděaše | vedi |

| 3 sg. | vedetъ | vede | vede | vede | veděaše | vedi |

| 1 dual | vedevě | vedově | věsově | vedoxově | veděaxově | veděvě |

| 2 dual | vedeta | vedeta | věsta | vedosta | veděašeta | veděta |

| 3 dual | vedete | vedete | věste | vedoste | veděašete | |

| 1 plural | vedemъ | vedomъ | věsomъ | vedoxomъ | veděaxomъ | veděmъ |

| 2 plural | vedete | vedete | věste | vedoste | veděašete | veděte |

| 3 plural | vedǫtъ | vedǫ | věsę | vedošę | veděaxǫ |

Basis

Template:Eastern Orthodox sidebar Written evidence of Old Church Slavonic survives in a relatively small body of manuscripts, most of them written in the First Bulgarian Empire during the late 10th and the early 11th centuries. The language has an Eastern South Slavic basis in the Bulgarian-Macedonian dialectal area, with an admixture of Western Slavic (Moravian) features inherited during the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius to Great Moravia (863–885).Template:Sfnp

The only well-preserved manuscript of the Moravian recension, the Kiev Missal, or the Kiev Folia, is characterised by the replacement of some South Slavic phonetic and lexical features with Western Slavic ones. Manuscripts written in the First Bulgarian Empire have, on the other hand, few Western Slavic features.

Though South Slavic in phonology and morphology, Old Church Slavonic was influenced by Byzantine Greek in syntax and style, and is characterized by complex subordinate sentence structures and participial constructions.Template:Sfnp

A large body of complex, polymorphemic words was coined, first by Saint Cyril himself and then by his students at the academies in Great Moravia and the First Bulgarian Empire, to denote complex abstract and religious terms, e.g., Template:Script (zъlodějanьje) from Template:Script ('evil') + Template:Script ('do') + Template:Script (noun suffix), i.e., 'evil deed'. A significant part of them wеrе calqued directly from Greek.Template:Sfnp

Old Church Slavonic is valuable to historical linguists since it preserves archaic features believed to have once been common to all Slavic languages such as:

- Most significantly, the yer (extra-short) vowels: Template:IPA and Template:IPA

- Nasal vowels: Template:IPA and Template:IPA

- Near-open articulation of the yat vowel (Template:IPA)

- Palatal consonants Template:IPA and Template:IPA from Proto-Slavic *ň and *ľ

- Proto-Slavic declension system based on stem endings, including those that later disappeared in attested languages (such as u-stems)

- Dual as a distinct grammatical number from singular and plural

- Aorist, imperfect, Proto-Slavic paradigms for participles

Old Church Slavonic is also likely to have preserved an extremely archaic type of accentuation (probably close to the Chakavian dialect of modern Serbo-Croatian), but unfortunately, no accent marks appear in the written manuscripts.

The South Slavic and Eastern South Slavic nature of the language is evident from the following variations:

- Phonetic:

- ra, la by means of liquid metathesis of Proto-Slavic *or, *ol clusters

- sě from Proto-Slavic *xě < *xai

- cv, (d)zv from Proto-Slavic *kvě, *gvě < *kvai, *gvai

- Morphological:

- Morphosyntactic use of the dative possessive case in personal pronouns and nouns: Template:Script (bratŭ mi, "my brother"), Template:Script (rǫka ti, "your hand"), Template:Script (otŭpuštenĭje grěxomŭ, "remission of sins"), Template:Script (xramŭ molitvě, 'house of prayer'), etc.

- periphrastic future tense using the verb Template:Script (xotěti, "to want"), for example, Template:Script (xoštǫ pisati, "I will write")

- Use of the comparative form Template:Script (mĭniji, "smaller") to denote "younger"

- Morphosyntactic use of suffixed demonstrative pronouns Template:Script (tъ, ta, to). In Bulgarian and Macedonian, these developed into suffixed definite articles and also took the place of the third person singular and plural pronouns Template:Script (onъ, ona, ono, oni) > Template:Script ('he, she, it, they')

Old Church Slavonic also shares the following phonetic features only with Bulgarian:

- Near-open articulation *æ / *jæ of the Yat vowel (ě); still preserved in the Bulgarian dialects of the Rhodope mountains, the Razlog dialect, the Shumen dialect and partially preserved as *ja (ʲa) across Yakavian Eastern Bulgarian

- Template:IPA and Template:IPA as reflexes of Proto-Slavic *ťʲ (< *tj and *gt, *kt) and *ďʲ (< *dj).

| Proto-Slavic | Old Church Slavonic | Bulgarian | Macedonian | Serbo-Croatian | Slovenian | Slovak | Czech | Polish | RussianTemplate:Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template:IPA medja ('boundary') |

Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align |

| Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | |

| Template:IPA světja ('candle') |

Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align |

| Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align | Template:Align |

Local influences (recensions)

Over time, the language adopted more and more features from local Slavic vernaculars, producing different variants referred to as Recensions or Redactions. Modern convention differentiates between the earliest, classical form of the language, referred to as Old Church Slavonic, and later, vernacular-coloured forms, collectively designated as Church Slavonic.Template:Sfnp More specifically, Old Church Slavonic is exemplified by extant manuscripts written between the 9th and 11th century in Great Moravia and the First Bulgarian Empire.

Great Moravia

The language was standardized for the first time by the mission of the two apostles to Great Moravia from 863. The manuscripts of the Moravian recension are therefore the earliest dated of the OCS recensions.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt "The seven glagolitic folia known as the Kiev Folia (KF) are generally considered as most archaic from both the paleographic and the linguistic points of view..."</ref> The recension takes its name from the Slavic state of Great Moravia which existed in Central Europe during the 9th century on the territory of today's Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, northern Austria and southeastern Poland.

Moravian recension

This recension is exemplified by the Kiev Missal. Its linguistic characteristics include:

- Confusion between the letters Big yus ⟨Ѫѫ⟩ and Uk ⟨Ѹѹ⟩ – this occurs once in the Kiev Folia, when the expected form въсоудъ vъsudъ is spelled въсѫдъ vъsǫdъ

- Template:IPA from Proto-Slavic *tj, use of Template:IPA from *dj, Template:IPA *skj

- Use of the words mьša, cirky, papežь, prěfacija, klepati, piskati etc.

- Preservation of the consonant cluster Template:IPA (e.g. modlitvami)

- Use of the ending –ъmь instead of –omь in the masculine singular instrumental, use of the pronoun čьso

First Bulgarian Empire

Although the missionary work of Constantine and Methodius took place in Great Moravia, it was in the First Bulgarian Empire that early Slavic written culture and liturgical literature really flourished.Template:Sfnp The Old Church Slavonic language was adopted as state and liturgical language in 893, and was taught and refined further in two bespoke academies created in Preslav (Bulgarian capital between 893 and 972), and Ohrid (Bulgarian capital between 991/997 and 1015).<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

The language did not represent one regional dialect but a generalized form of early eastern South Slavic, which cannot be localized.<ref name= "Old Church Slavonic, Horace Lunt">Template:Harvp.</ref> The existence of two major literary centres in the Empire led in the period from the 9th to the 11th centuries to the emergence of two recensions (otherwise called "redactions"), termed "Eastern" and "Western" respectively.Template:Sfnp<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Some researchers do not differentiate between manuscripts of the two recensions, preferring to group them together in a "Macedo-Bulgarian"<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> or simply "Bulgarian" recension.Template:Sfnp<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="usa" /> The development of Old Church Slavonic literacy had the effect of preventing the assimilation of the South Slavs into neighboring cultures, which promoted the formation of a distinct Bulgarian identity.Template:Sfnp

Common features of both recensions:

- Consistent use of the soft consonant clusters Template:Script (*ʃt) & Template:Script (*ʒd) for Pra-Slavic *tj/*gt/*kt and *dj. Articulation as *Template:IPAlink & *Template:IPAlink in a number of Macedonian dialects is a later development due to Serbian influence in the Late Middle Ages, aided by Late Middle Bulgarian's mutation of palatal *Template:IPAlink & *Template:IPAlink > palatal k & g<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Sfnp<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

- Consistent use of the yat vowel (ě)

- Inconsistent use of the epenthetic l, with attested forms both with and without it: korabĺь & korabъ, zemĺě & zemьja, the latter possibly indicating a shift from <ĺ> to <j>.Template:SfnpTemplate:Sfnp Modern Bulgarian/Macedonian lack epenthetic l

- Replacement of the affricate Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink) with the fricative Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink), realized consistently in Cyrillic and partially in Glagolitic manuscriptsTemplate:Sfnp

- Use of the past participle in perfect and past perfect tense without an auxiliary to denote the narator's attitude to what is happeningTemplate:Sfnp

Moreover, consistent scribal errors indicate the following trends in the development of the recension(s) between the 9th and the 11th centuries:

- Loss of the yers (Template:Script & Template:Script) in weak position and their vocalization in strong position, with diverging results in Preslav and OhridTemplate:SfnpTemplate:SfnpTemplate:Sfnp

- Depalatalization of Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink), Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink), Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink), Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink), Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink), and the Template:Script clusters.Template:Sfnp They are only hard in modern Bulgarian/Macedonian/Torlak

- Loss of intervocalic Template:IPAslink, followed by vowel assimilation and contraction: sěěhъ (denoting sějahъ) > sěahъ > sěhъ ('I sowed'), dobrajego > dobraego > dobraago > dobrago ('good', masc. gen. sing.)Template:SfnpTemplate:Sfnp

- Incipient denasalization of the small yus, Template:Script (ę), replaced with Template:Script (e)Template:Sfnp

- Loss of the present tense third person sing. ending Template:Script (tъ), e.g., Template:Script (bǫdetъ) > Template:Script (bǫde) (lacking in modern Bulgarian/Macedonian/Torlak)Template:Sfnp

- Incipient replacement of the sigmatic and asigmatic aorist with the new aorist, e.g., vedoxъ instead of vedъ or věsъ (modern Bulgarian/Macedonian and, in part, Torlak use similar forms)Template:Sfnp

- Incipent analytisms, including examples of weakening of the noun declension, use of a postpositive definite article, infinitive decomposition > use of da constructions, future tense with Template:Script (> Template:Script in Bulgarian/Macedonian/Torlak) can all be observed in 10-11th century manuscriptsTemplate:Sfnp

There are also certain differences between the Preslav and Ohrid recensions. According to Huntley, the primary ones are the diverging development of the strong yers (Western: Template:Script > Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink) and Template:Script > Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink), Eastern Template:Script and Template:Script > *Template:IPAlink), and the palatalization of dentals and labials before front vowels in East but not West.Template:Sfnp These continue to be among the primary differences between Eastern Bulgarian and Western Bulgarian/Macedonian to this day. Moreover, two different styles (or redactions) can be distinguished at Preslav; Preslav Double-Yer (Template:Script ≠ Template:Script) and Preslav Single-Yer (Template:Script = Template:Script, usually > Template:Script). The Preslav and Ohrid recensions are described in greater detail below:

Preslav recension

The manuscripts of the Preslav recension<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Sfnp<ref name="Kamusella 2008">Template:HarvpTemplate:Page needed.</ref> or "Eastern" variantTemplate:Sfnp are among the oldest of the Old Church Slavonic language, only predated by the Moravian recension. This recension was centred around the Preslav Literary School. Since the earliest datable Cyrillic inscriptions were found in the area of Preslav, it is this school which is credited with the development of the Cyrillic alphabet which gradually replaced the Glagolitic one.Template:Sfnp<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> A number of prominent Bulgarian writers and scholars worked at the Preslav Literary School, including Naum of Preslav (until 893), Constantine of Preslav, John Exarch, Chernorizets Hrabar, etc.. The main linguistic features of this recension are the following:

- The Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets were used concurrently

- In some documents, the original supershort vowels Template:Script and Template:Script merged with one letter taking the place of the other

- The original ascending reflex (rь, lь) of syllabic Template:IPA and Template:IPA was sometimes metathesized to (ьr, ьl), or a combination of the two

- The central vowel ы (ꙑ) merged with ъи (ъj)

- Merger of Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink) and Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink)

- The verb forms Template:Script (naricajǫ, naricaješi) were substituted or alternated with Template:Script (naričjajǫ, naričjaješi)

Ohrid recension

The manuscripts of the Ohrid recension or "Western" variantTemplate:Sfnp are among the oldest of the Old Church Slavonic language, only predated by the Moravian recension. The recension is sometimes named Macedonian because its literary centre, Ohrid, lies in the historical region of Macedonia. At that period, Ohrid administratively formed part of the province of Kutmichevitsa in the First Bulgarian Empire until the Byzantine conquest.Template:Sfnp The main literary centre of this dialect was the Ohrid Literary School, whose most prominent member and most likely founder, was Saint Clement of Ohrid who was commissioned by Boris I of Bulgaria to teach and instruct the future clergy of the state in the Slavonic language. This recension is represented by the Codex Zographensis and Marianus, among others. The main linguistic features of this recension include:

- Continuous usage of the Glagolitic alphabet instead of Cyrillic

- Strict distinction in the articulation of the yers and their vocalisation in strong position (ъ > *Template:IPAlink and ь > *Template:IPAlink) or deletion in weak position<ref name="Huntley 1993 126–7"/>

- Wider usage and retention of the phoneme *Template:IPAlink (which in most other Slavic languages has dеaffricated to *Template:IPAlink)

Later recensions

Template:Main Old Church Slavonic may have reached Slovenia as early as Cyril and Methodius's Panonian mission in 868 and is exemplified by the late 10th century Freising fragments, written in the Latin script.Template:Sfnp Later, in the 10th century, Glagolitic liturgy was carried from Bohemia to Croatia, where it established a rich literary tradition.Template:Sfnp Old Church Slavonic in the Cyrillic script was in turn transmitted from Bulgaria to Serbia in the 10th century and to Kievan Rus' in connection with its adoption of Orthodox Christianity in 988.Template:SfnpTemplate:Sfnp

The later use of Old Church Slavonic in these medieval Slavic polities resulted in a gradual adjustment of the language to the local vernacular, while still retaining a number of Eastern South Slavic, Moravian or Bulgarian features. In all cases, yuses denasalised so that only Old Church Slavonic, modern Polish and some isolated Bulgarian dialects retained the old Slavonic nasal vowels.

Five major recensions with such vernacular "accommodations" can be identified: the Czech-Moravian or Bohemian recension, which originated in the original mission in Great Moravia but became moribund as early as the late 1000s; (Middle) Bulgarian, which continued the literary tradition of the Preslav and Ohrid Literary Schools; Croatian, associated with the continued use of the Glagolitic alphabet; Serbian, known for at least four separate recensions; and Russian, which came to dominance in the 1800s.Template:Sfnp

Certain authors also talk about separate Bosnian and Ruthenian recensions, whereas the use of the Bulgarian Euthymian recension in Wallachia and Moldova from the late 1300s until the early 1700s is sometimes referred to as "Daco-Slavonic" or "Dacian" recension.Template:Sfnp All of these later versions of Old Church Slavonic are collectively referred to as Church Slavonic.Template:Sfnp

Bohemian (Czech-Moravian) recension

The Bohemian (Czech) recension is derived from the Moravian recension and was used in the Czech lands until 1097. It was written in Glagolitic, which is posited to have been carried over to Bohemia even before the death of Methodius.Template:Sfnp It is preserved in religious texts (e.g. Prague Fragments), legends and glosses and shows substantial influence of the Western Slavic vernacular in Bohemia at the time. Its main features are:<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

- PSl. *tj, *kt(i), *dj, *gt(i) → c /ts/, z: pomocь, utvrьzenie

- PSl. *stj, *skj → šč: *očistjenьje → očiščenie

- ending -ъmь in instr. sg. (instead of -omь): obrazъmь

- verbs with prefix vy- (instead of iz-)

- promoting of etymological -dl-, -tl- (světidlъna, vъsedli, inconsistently)

- suppressing of epenthetic l (prěstavenie, inconsistently)

- -š- in original stem vьx- (všěx) after 3rd palatalization

- development of yers and nasals coincident with development in Czech lands

- fully syllabic r and l

- ending -my in first-person pl. verbs

- missing terminal -tь in third-person present tense indicative

- creating future tense using prefix po-

- using words prosba (request), zagrada (garden), požadati (to ask for), potrěbovati (to need), conjunctions aby, nebo, etc.

Bosnian recension

The Bosnian recension used both the Glagolitic alphabet and the Cyrillic alphabet. A home-grown version of the Cyrillic alphabet, commonly known as Bosančica, or Bosnian Cyrillic, coined as neologism in 19th century, emerged very early on (probably the 1000s).Template:Sfnp<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Sfnp Primary features:

- Use of the letters i, y, ě for *Template:IPAlink in Bosnian manuscripts (reflecting Bosnian Ikavism)

- Use of the letter djerv (Ꙉꙉ) for the Serbo-Croatian reflexes of Pra-Slavic *tj and *dj (*Template:IPAlink & *Template:IPAlink)

- Djerv was also used denote palatal *l and *n: Template:Script = *Template:IPAlink, Template:Script = *Template:IPAlink

- Use of the letter Щщ for Pra-Slavic *stj, *skj (reflecting pronunciation as *ʃt or *ʃt͡ʃ) and only rarely for *tj

The recension has been subsumed under the Serbian recension, especially by Serbian linguistics, and (along with Bosančica) is the subject of a dispute between Serbs, Croatians and Bosniaks.Template:Sfnp

Middle Bulgarian

The common term "Middle Bulgarian" is usually contrasted to "Old Bulgarian" (an alternative name for Old Church Slavonic) and is loosely used for manuscripts whose language demonstrates a broad spectrum of regional and temporal dialect features after the 11th century.<ref>Gerald L. Mayer, 1988, The definite article in contemporary standard Bulgarian, Freie Universität Berlin. Osteuropa-Institut, Otto Harrassowitz, p. 108.</ref><ref>Template:Cite encyclopedia</ref>Template:Sfnp An alternative term, Bulgarian recension of Church Slavonic, is used by some authors.Template:Sfnp

Unlike the Old Bulgarian period, centres other than the capital of Tarnovo are only loosely defined, and designating individual recensions is difficult. Until St. Euthymius' reform, orthographies were not standardised, varying not only based on place and time―reflecting a language in phonetic and grammatical flux―but also by manuscript type and education and experience of the copyist. Lay works and manuscripts of less polished copyists, e.g., The Popular Vita of St. John of Rila of the late 1100s, the early 1200s Dobreyshovo Gospels or the early 1300s Troy Story exhibit far more and advanced analytical features than established canonical texts.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>Template:Sfnp

Middle Bulgarian is generally defined as a transition from the synthetic Old Bulgarian to the highly analytic New Bulgarian and Macedonian, where incipient 10th-century analytisms gradually spread from the north-east to all Bulgarian, Macedonian and Torlakian dialects. Primary features:

Phonological:

- Merger of the yuses, *ǫ=*ę (Ѫѫ=Ѧѧ), into a single mid back unrounded vowel (most likely ʌ̃), where ѫ was used after plain and ѧ after palatal consonants (1000s–1100s), followed by denasalization and transition of ѫ > *Template:IPAlink or *Template:IPAlink and ѧ > *Template:IPAlink in most dialects (1200s-1300s)Template:Sfnp<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

- Str. *ě > *ja (ʲa) in Eastern Bulgarian, starting from the 1100s; Template:Script (vjanec) instead of Template:Script (v(j)ænec), from earlier Template:Script (v(j)ænьc) ('wreath'), after vocalization of the strong front yerTemplate:Sfnp

- *ě > *e starting from northwestern Macedonia and spreading east and south, 1200sTemplate:Sfnp

- *cě > *ca & *dzě > *dza in eastern North Macedonia and western Bulgaria (yakavian at the time), Template:Script (calovati) instead of Template:Script (c(j)ælovati) ('kiss'), indicating hardening of palatal *c & *dz before *ě, 1200sTemplate:Sfnp

- Merger of the yuses and yers (*ǫ=*ę=*ъ=*ь), usually, but not always, into a schwa-like sound (1200–1300s) in some dialects (central Bulgaria, the Rhodopes).Template:Sfnp Merger preserved in the most archaic Rup dialects, e.g., Smolyan (> Template:IPAlink), Paulician (incl. Banat Bulgarian), Zlatograd, Hvoyna (all > Template:IPAlink)

Morphological:

- Degradation of the noun declension and incorrect use of most cases or their replacement of preposition + dative or accusative by the late 1300sTemplate:Sfnp

- Further development and grammaticalization of the short demonstrative pronouns into postpositive definite articles, e.g., Template:Script ('the sweetness')Template:Sfnp

- Emergence of analytic comparative of adjectives, Template:Script ('richer'), Template:Script ('better') by the 1300sTemplate:Sfnp

- Emergence of a single plural form for adjectives by the 1300s

- Disappearance of the supine, replaced by the infinitive, which in turn was replaced by da + present tense constructions by the late 1300s

- Disappearance of the present active, present passive and past active participle and the widening of the use of the l-participle (reklъ) and the past passive participle (rečenъ) ('said')

- Replacement of aorist plural forms -oxomъ, -oste, -ošę with -oxmy/oxme, -oxte, -oxǫ as early as the 1100s, e.g., Template:Script (rekoxǫ) instead of Template:Script (rekošę) ('they said')Template:Sfnp

Pre-Euthymian Tarnovo recension:

- Regular vocalisation Template:Script > Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink) in both suffixes and roots, e.g., Template:Script (tvorecъ) ('creator'), Template:Script (levъ) ('lion') and notation with a back yer (Template:Script) if the root yer is weak―Template:Script (tъmenъ) ('dark, m. s.')<ref name="TarnLit9">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="St.Petka">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="TarnLit4">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Palaeobulgarica2024">Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Vocalisation Template:Script > Template:Script (*Template:IPAlink) in the suffixes -ъk-, -ъv- and definite articles: Template:Script (svitokъ) ('scroll'), Template:Script (ʎubovъ) ('love'), Template:Script (rodotъ) ('the kin')<ref name="TarnLit9"/><ref name="St.Petka"/><ref name="Palaeobulgarica2024"/>

- *y is written correctly in its etymological places<ref name="St.Petka"/>

- *ž, *š, *žd and *št are followed by hard vowels (*ǫ, *u), signifying early depalatalisation<ref name="TarnLit9"/><ref name="Palaeobulgarica2024"/>

- *č, the old palatals *ɼ, *ʎ, *ɲ and the newly palatalised labials are followed by soft/iotated vowels (*ę, *ju) as an indication they are still palatalised<ref name="TarnLit9"/><ref name="Palaeobulgarica2024"/><ref name="TarnLit4"/>

- *a is not iotated word-initially in a number of words, e.g., Template:Script (agnę) ('lamb'), Template:Script (ablъko) ('apple'), Template:Script (agoda) ('strawberry')<ref name="TarnLit9"/><ref name="Palaeobulgarica2024"/>

- Use of triple definite article based on the short demonstrative pronouns Template:Script, Template:Script & Template:Script, e.g., Template:Script (svitъkosъ) ('the scroll right next to me')―typical for all Middle Bulgarian dialects<ref name="TarnLit9"/>

- Growing avoidance of iotated vowels: *ja > *ě, *jǫ > *ǫ, *ję > *ę, *je > *e (eventually codified in the Euthymian recension)<ref name="St.Petka"/><ref name="Palaeobulgarica2024"/>

- Swapping the two yuses according to somewhat artificial rules (also codified in the Euthymian recension)<ref name="TarnLit4"/><ref name="Palaeobulgarica2024"/><ref name="St.Petka"/>

Most norms reflect the developments in the Moesian dialectal basis of the Tarnovo region at the time.

Euthymian recension

In the early 1370s, Bulgarian Patriarch Euthymius of Tarnovo implemented a reform to standardize Bulgarian orthography.Template:Sfnp Instead of bringining the language closer to that of commoners, the "Euthymian", or Tarnovo, recension, rather sought to re-establish older Old Church Slavonic models, further archaizing it.Template:Sfnp The fall of Bulgaria under Ottoman rule in 1396 precipitated an exodus of Bulgarian men-of-letters, e.g., Cyprian, Gregory Tsamblak, Constantine of Kostenets, etc. to Wallachia, Moldova and the Grand Duchies of Lithuania and Moscow, where they enforced the Euthymian recension as liturgical and chancery language, and to the Serbian Despotate, where it influenced the Resava School.Template:SfnpTemplate:Sfnp

Croatian recension

The Croatian recension of Old Church Slavonic used only the Glagolitic alphabet of angular type. It shows the development of the following characteristics:

- Denasalisation of PSl. *ę > e, PSl. *ǫ > u, e.g., OCS rǫka ("hand") > Cr. ruka, OCS językъ > Cr. jezik ("tongue, language")

- PSl. *y > i, e.g., OCS byti > Cr. biti ("to be")

- PSl. weak-positioned yers *ъ and *ь merged, probably representing some schwa-like sound, and only one of the letters was used (usually 'ъ'). Evident in earliest documents like Baška tablet.

- PSl. strong-positioned yers *ъ and *ь were vocalized into *a in most Štokavian and Čakavian dialects, e.g., OCS pьsъ > Cr. pas ("dog")

- PSl. hard and soft syllabic liquids *r and *r′ retained syllabicity and were written as simply r, as opposed to OCS sequences of mostly rь and rъ, e.g., krstъ and trgъ as opposed to OCS krьstъ and trъgъ ("cross", "market")

- PSl. #vьC and #vъC > #uC, e.g., OCS. vъdova ("widow") > Cr. udova

Russian recension

The Russian recension emerged in the 1000s based on the earlier Eastern Bulgarian recension, from which it differed slightly. The earliest manuscript to contain Russian elements is the Ostromir Gospel of 1056–1057, which exemplifies the beginning of a Russianized Church Slavonic that gradually spread to liturgical and chancery documents.Template:Sfnp The Russianization process was cut short in the late 1300s, when a series of Bulgarian prelates, starting with Cyprian, consciously "re-Bulgarized" church texts to achieve maximum conformity with the Euthymian recension.Template:SfnpTemplate:Sfnp The Russianization process resumed in the late 1400s but was sluggish due to the clergy's hostility towards vernacular use, which they regarded as "contamination of the holy language", and towards using Cyrillics to write any idiom other than Church Slavonic―which was similarly deemed "sacrilegious".Template:Sfnp Nevertheless, Russian Church Slavonic eventually stabilised and even started projecting influence outwards, until it became entrenched as the de facto standard for all Orthodox Slavs, incl. Serbs and Bulgarians, by the early 1800s.Template:Sfnp Characteristics:

- PSl. *ę > *ja/ʲa, PSl. *ǫ > u, e.g., OCS rǫka ("hand") > Rus. ruka; OCS językъ > Rus. jazyk ("tongue, language")<ref>Template:Harvp</ref>

- Vocalisation of the yers in strong position (ъ > *Template:IPAlink and ь > *Template:IPAlink) and their deletion in weak position

- *ě > *e, e.g., OCS věra ("faith") > Rus. vera

- Preservation of a number of South Slavic and Bulgarian phonological and morphological features, which also carried to the Russian language, e.g.Template:Sfnp

- - Use of Template:Script (pronounced *ʃt͡ʃ) instead of East Slavic Template:Script (*t͡ʃ) for Pra-Slavic *tj/*gt/*kt: cf. Russian Template:Script (prosveščenie) vs. Ukrainian Template:Script (osvičennja) ('illumination')

- - Use of Template:Script (*ʒd) instead of East Slavic Template:Script (*ʒ) for Pra-Slavic *dj: cf. Russian Template:Script (odežda) vs. Ukrainian Template:Script (odeža) ('clothing')

- - Non-pleophonic -ra/-la instead of East Slavic pleophonic -oro/-olo forms: cf. Russian Template:Script (nagrada) vs. Ukrainian Template:Script (nahoroda) ('reward')

- - Prefixes so-/voz-/iz- instead of s-/vz- (z-)/vy-: cf. Russian Template:Script (vozbuditь) vs. Ukrainian Template:Script (zbudyty) ('arouse'), etc.

Ruthenian recension

The Ruthenian recension generally shows the same characteristics as and is usually subsumed under the Russian recension. The Euthymian recension that was pursued throughout the 1400s was gradually replaced in the 1500s by Ruthenian, an administrative language based on the Belarusian dialect of Vilno.Template:Sfnp

Serbian recension

The Serbian recension initially employed both the Glagolitic alphabet and the Cyrillic alphabet, but Cyrillic eventually prevailed and was the only script used from the 1200s onwards (apart from limited use of Latin script in coastal areas).Template:SfnpTemplate:Sfnp

A home-grown side version of the Cyrillic alphabet, commonly known as Serbian Cyrillic, emerged very early on (probably the 10th century).

The penetration of Serbian vernacular phonemes into liturgical texts led to the stabilization of a Serbian pronunciation of Old Church Slavonic and the development of graphic and orthographic solutions. Over time, this evolution produced the Zeta-Hum, Raška, and Resava orthographic schools, named after their respective locations.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

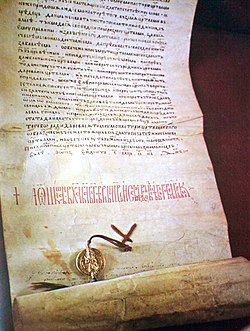

The one of oldest preserved manuscript written in the Serbian recension is the Miroslav Gospel, dated to 1180, commissioned by brother of the Great Prince of Serbia Stefan Nemanja. Today is a Serbia UNESCO's Memory of the World international register.

Primary features:

- Nasal vowels were denasalised and in one case closed: *ę > e, *ǫ > u, e.g. OCS rǫka > Sr. ruka ("hand"), OCS językъ > Sr. jezik ("tongue, language")

- Notable extensive use ofdiacritical signs by the Resava School

- Use of letters i, y for the sound Template:IPA in other manuscripts of the Serbian recension

- Use of the Old Serbian Letter djerv (Ꙉꙉ) for the Serbian reflexes of Pre-Slavic *tj and *dj (*Template:IPAlink, *Template:IPAlink, *Template:IPAlink, and *Template:IPAlink)

Resava variant

Due to the Ottoman conquest of Bulgaria in 1396, Serbia saw an influx of educated scribes and clergy, who re-introduced a more classical form that resembled more closely the Bulgarian recension. The Resava recension developed around the Resava Literary School, founded by the order of Serbian Despot Stefan Lazarević in the early 1400s and led by Bulgarian scholar Constantine of Kostenets.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The recension was closely modelled on the Euthymian one, with etymological use of *ě (yat), *y (yery), etc., use of Bulgarian ⟨щ⟩ (*ʃt) and ⟨жд⟩ (*ʒd) for Pra-Slavic *tj/*gt/*kt and *dj, but replacing yuses with Serbian reflexes *ę > e & *ǫ > u.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In the late 1400s and early 1500s, the Resava orthography spread to Bulgaria and North Macedonia and exerted substantial influence on Wallachia. It was eventually superseded by Russian Church Slavonic in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Role in modern Slavic languages

Old Church Slavonic was initially widely intelligible across the Slavic world.Template:Sfnp However, with the gradual differentiation of individual languages, Orthodox Slavs and, to some extent, Croatians ended up in a situation of diglossia, where they used one Slavic language for religious and another one for everyday affairs.Template:Sfnp The resolution of this situation, and the choice made for the exact balance between Old Church Slavonic and vernacular elements and forms is key to understanding the relationship between (Old) Church Slavonic and modern Slavic literary languages, as well as the distance between individual languages.Template:Sfnp

It was first Russian polymath and grammarian Mikhail Lomonosov that defined in 1755 "three styles" to the balance of Church Slavonic and Russian elements in the Russian literary language: a high style—with substantial Old Church Slavonic influence—for formal occasions and heroic poems; a low style—with substantial influence of the vernacular—for comedy, prose and ordinary affairs; and a middle style, balancing between the two, for informal verse epistles, satire, etc.Template:SfnpTemplate:Sfnp

The middle, "Slaveno-Russian", style eventually prevailed.Template:Sfnp Thus, while standard Russian was codified on the basis of the Central Russian dialect and the Moscow chancery language, it retains an entire stylistic layer of Church Slavonisms with typically Eastern South Slavic phonetic features.Template:Sfnp Where native and Church Slavonic terms exist side by side, the Church Slavonic one is in the higher stylistic register and is usually more abstract, e.g., the neutral Template:Script (gorod) vs. the poetic Template:Script (grаd) ('town').Template:Sfnp

Bulgarian faced a similar dilemma a century later, with three camps championing Church Slavonic, Slaveno-Bulgarian, and New Bulgarian as a basis for the codification of modern Bulgarian.Template:Sfnp Here the proponents of the analytic vernacular eventually won. However, the language re-imported a vast number of Church Slavonic forms, regarded as a legacy of Old Bulgarian, either directly from Russian Church Slavonic or through the mediation of Russian.Template:Sfnp

By contrast, Serbian made a clean break with (Old) Church Slavonic in the first half of the 1800s, as part of Vuk Karadžić's linguistic reform, opting instead to build the modern Serbian language from the ground up, based on the Eastern Herzegovinian dialect. Ukrainian and Belarusian as well as Macedonian took a similar path in the mid and late 1800s and the late 1940s, respectively, the former two because of the association of Old Church Slavonic with stifling Russian imperial control and the latter in an attempt to distance the newly-codified language as further away from Bulgarian as possible.Template:SfnpTemplate:Sfnp

Canon

The core corpus of Old Church Slavonic manuscripts is usually referred to as canon. Manuscripts must satisfy certain linguistic, chronological and cultural criteria to be incorporated into the canon: they must not significantly depart from the language and tradition of Saints Cyril and Methodius, usually known as the Cyrillo-Methodian tradition.

For example, the Freising Fragments, dating from the 10th century, show some linguistic and cultural traits of Old Church Slavonic, but they are usually not included in the canon, as some of the phonological features of the writings appear to belong to certain Pannonian Slavic dialect of the period. Similarly, the Ostromir Gospels exhibits dialectal features that classify it as East Slavic, rather than South Slavic so it is not included in the canon either. On the other hand, the Kiev Missal is included in the canon even though it manifests some West Slavic features and contains Western liturgy because of the Bulgarian linguistic layer and connection to the Moravian mission.

Manuscripts are usually classified in two groups, depending on the alphabet used, Cyrillic or Glagolitic. With the exception of the Kiev Missal and Glagolita Clozianus, which exhibit West Slavic and Croatian features respectively, all Glagolitic texts are assumed to be of the Macedonian recension:

- Kiev Missal (Ki, KM), 7 folios, late 10th century

- Codex Zographensis, (Zo), 288 folios, 10th or 11th century

- Codex Marianus (Mar), 173 folios, early 11th century

- Codex Assemanius (Ass), 158 folios, early 11th century

- Psalterium Sinaiticum (Pas, Ps. sin.), 177 folios, 11th century

- Euchologium Sinaiticum (Eu, Euch), 109 folios, 11th century

- Glagolita Clozianus (Clo, Cloz), 14 folios, 11th century

- Ohrid Folios (Ohr), 2 folios, 11th century

- Rila Folios (Ri, Ril), 2 folios and 5 fragments, 11th century

All Cyrillic manuscripts are of the Preslav recension (Preslav Literary School) and date from the 11th century except for the Zographos, which is of the Ohrid recension (Ohrid Literary School):

- Sava's book (Sa, Sav), 126 folios

- Codex Suprasliensis, (Supr), 284 folios

- Enina Apostle (En, Enin), 39 folios

- Hilandar Folios (Hds, Hil), 2 folios

- Undol'skij's Fragments (Und), 2 folios

- Macedonian Folio (Mac), 1 folio

- Zographos Fragments (Zogr. Fr.), 2 folios

- Sluck Psalter (Ps. Sl., Sl), 5 folios

Sample text

Here is the Lord's Prayer in Old Church Slavonic:

| Cyrillic | IPA | Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

Authors

The history of Old Church Slavonic writing includes a northern tradition begun by the mission to Great Moravia, including a short mission in the Lower Pannonia, and a Bulgarian tradition begun by some of the missionaries who relocated to Bulgaria after the expulsion from Great Moravia.

The first texts written in Old Church Slavonic are translations of the Gospels and Byzantine liturgical texts<ref name=Catholic_Encyclopedia/> begun by the Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius, mostly during their mission to Great Moravia.

The most important authors in Old Church Slavonic after the death of Methodius and the dissolution of the Great Moravian academy were Clement of Ohrid (active also in Great Moravia), Constantine of Preslav, Chernorizetz Hrabar and John Exarch, all of whom worked in medieval Bulgaria at the end of the 9th and the beginning of the 10th century. The full text of the Second Book of Enoch is only preserved in Old Church Slavonic, although the original most certainly had been in Greek or even Hebrew or Aramaic.

Software

PISMO: a cross-platform (Windows, Macintosh, Linux) open source software package is now available for digitizing Slavic texts.

https://richmondmathewson.owlstown.net/pages/8572-pismo

Modern Slavic nomenclature

Here are some of the names used by speakers of modern Slavic languages:

- Template:Langx (staraslavjanskaja mova), 'Old Slavic language'

- Template:Langx (starobǎlgarski), 'Old Bulgarian' and старославянски,<ref>Иванова-Мирчева 1969: Д. Иванова-Мнрчева. Старобългарски, старославянски и средно-българска редакция на старославянски. Константин Кирил Философ. В Юбилеен сборник по случай 1100 годишнината от смъртта му, стр. 45–62.</ref> (staroslavjanski), 'Old Slavic'

- Template:Langx, 'Old Slavic'

- Template:Langx (staroslovenski), 'Old Slavic'

- Template:Langx, 'Old Church Slavic'

- Template:Langx (staroslavjanskij jazyk), 'Old Slavic language'

- Template:Langx (Bosnian,<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Croatian<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>), Template:Langx/Template:Langx (Serbian<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>), 'Old Slavic'

- Template:Langx, 'Old Slavic'

- Template:Langx, 'Old Church Slavic'

- Template:Langx (starocerkovnoslov"jans'ka mova), 'Old Church Slavic language'

See also

- Outline of Slavic history and culture

- List of Slavic studies journals

- History of the Bulgarian language

- Church Slavonic language

- Old East Slavic

- List of Glagolitic manuscripts

- Proto-Slavic language

- Slavonic-Serbian

Notes

References

Bibliography

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book Template:Open access

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

External links

Template:InterWiki Template:Wikibooks Template:Commons category Template:WikisourceWiki

- Old Church Slavonic Online by Todd B. Krause and Jonathan Slocum, free online lessons at the Linguistics Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Ein praktisches Lehrbuch des Kirchenslavischen. Band I: Altkirchenslavisch by Nicolina Trunte, free online 418-page textbook of Old Church Slavonic (scroll down)

- Medieval Slavic Fonts on AATSEEL

- Old Slavic data entry application

- Corpus Cyrillo-Methodianum Helsingiense: An Electronic Corpus of Old Church Slavonic Texts

- Research Guide to Old Church Slavonic

- Bible in Old Church Slavonic language – Russian redaction (Wikisource), (PDF) Template:Webarchive, (iPhone), (Android)

- Old Church Slavonic and the Macedonian recension of the Church Slavonic language, Elka Ulchar Template:In lang

- Vittore Pisani, Old Bulgarian Language Template:Webarchive, Sofia, Bukvitza, 2012. English, Bulgarian, Italian.

- Philipp Ammon: Tractatus slavonicus. Template:Webarchive in: Sjani (Thoughts) Georgian Scientific Journal of Literary Theory and Comparative Literature, N 17, 2016, pp. 248–56

- Template:YouTube

- glottothèque – Ancient Indo-European Grammars online, an online collection of introductory videos to Ancient Indo-European languages produced by the University of Göttingen

- Church Slavonic Typography in Unicode (Unicode Technical Note no. 41), 2015-11-04, accessed 2023-01-04.

Template:Slavic languagesTemplate:Middle AgesTemplate:Authority control

- Pages with broken file links

- Languages attested from the 9th century

- Church Slavonic language

- History of Eastern Orthodoxy

- Great Moravia

- History of Macedonia (region)

- Christian liturgical languages

- Medieval Bulgarian literature

- Medieval languages

- Medieval Macedonia

- Medieval history of Serbia

- Eastern South Slavic

- Old Church Slavonic language