Operational amplifier

Template:Infobox electronic component

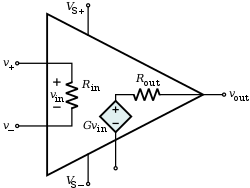

An operational amplifier (often op amp or opamp) is a DC-coupled electronic amplifier with a differential input, a (usually) single-ended output voltage,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and an extremely high gain. Its name comes from its original use of performing mathematical operations in analog computers. The voltage-feedback opamp (the focus of this article) amplifies the voltage difference between its two inputs, while the less common current-feedback op amp amplifes the current between its two inputs.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

By using negative feedback, an op amp circuit's characteristics (e.g. its gain, input and output impedance, bandwidth, and functionality) can be determined by external components and have little dependence on temperature coefficients or engineering tolerance in the op amp itself. This flexibility has made the op amp a popular building block in analog circuits.

Today, op amps are used widely in consumer, industrial, and scientific electronics. Many standard integrated circuit op amps cost only a few cents; however, some integrated or hybrid operational amplifiers with special performance specifications may cost over Template:Currency.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Op amps may be packaged as components or used as elements of more complex integrated circuits.

The op amp is one type of differential amplifier. Other differential amplifier types include the fully differential amplifier (an op amp with a differential rather than single-ended output), the instrumentation amplifier (usually built from three op amps), the isolation amplifier (with galvanic isolation between input and output), and negative-feedback amplifier (usually built from one or more op amps and a resistive feedback network).

Operation

The amplifier's differential inputs consist of a non-inverting input (+) with voltage Template:Math and an inverting input (−) with voltage Template:Math; ideally the op amp amplifies only the difference in voltage between the two, which is called the differential input voltage. The output voltage of the op amp Template:Math is given by the equation <math display=block>V_\text{out} = A_\text{OL} (V_+ - V_-),</math> where Template:Math is the open-loop gain of the amplifier (the term "open-loop" refers to the absence of an external feedback loop from the output to the input).

Open-loop amplifier

The magnitude of Template:Math is typically very large (100,000 or more for integrated circuit op amps, corresponding to +100 dB). Thus, even small microvolts of difference between Template:Math and Template:Math may drive the amplifier into clipping or saturation. The magnitude of Template:Math is not well controlled by the manufacturing process, and so it is impractical to use an open-loop amplifier as a stand-alone differential amplifier.

Without negative feedback, and optionally positive feedback for regeneration, an open-loop op amp acts as a comparator, although comparator ICs are better suited.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> If the inverting input of an ideal op amp is held at ground (0 V), and the input voltage Template:Math applied to the non-inverting input is positive, the output will be maximum positive; if Template:Math is negative, the output will be maximum negative.

Closed-loop amplifier

If predictable operation is desired, negative feedback is used, by applying a portion of the output voltage to the inverting input. The closed-loop feedback greatly reduces the gain of the circuit. When negative feedback is used, the circuit's overall gain and response is determined primarily by the feedback network, rather than by the op-amp characteristics. If the feedback network is made of components with values small relative to the op amp's input impedance, the value of the op amp's open-loop response Template:Math does not seriously affect the circuit's performance. In this context, high input impedance at the input terminals and low output impedance at the output terminal(s) are particularly useful features of an op amp.

The response of the op-amp circuit with its input, output, and feedback circuits to an input is characterized mathematically by a transfer function; designing an op-amp circuit to have a desired transfer function is in the realm of electrical engineering. The transfer functions are important in most applications of op amps, such as in analog computers.

In the non-inverting amplifier on the right, the presence of negative feedback via the voltage divider Template:Math, Template:Math determines the closed-loop gain Template:Math. Equilibrium will be established when Template:Math is just sufficient to pull the inverting input to the same voltage as Template:Math. The voltage gain of the entire circuit is thus Template:Math. As a simple example, if Template:Math and Template:Math, Template:Math will be 2 V, exactly the amount required to keep Template:Math at 1 V. Because of the feedback provided by the Template:Math, Template:Math network, this is a closed-loop circuit.

Another way to analyze this circuit proceeds by making the following (usually valid) assumptions:<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

- When an op amp operates in linear (i.e., not saturated) mode, the difference in voltage between the non-inverting (+) and inverting (−) pins is negligibly small.

- The input impedance of the (+) and (−) pins is much larger than other resistances in the circuit.

The input signal Template:Math appears at both (+) and (−) pins per assumption 1, resulting in a current Template:Mvar through Template:Math equal to Template:Math: <math display="block">i = \frac{V_\text{in}}{R_\text{g}}.</math>

Because Kirchhoff's current law states that the same current must leave a node as enter it, and because the impedance into the (−) pin is near infinity per assumption 2, we can assume practically all of the same current Template:Mvar flows through Template:Math, creating an output voltage <math display="block">V_\text{out} = V_\text{in} + iR_\text{f} = V_\text{in} + \left(\frac{V_\text{in}}{R_\text{g}} R_\text{f}\right) = V_\text{in} + \frac{V_\text{in}R_\text{f}} {R_\text{g}} = V_\text{in} \left(1 + \frac{R_\text{f}}{R_\text{g}}\right).</math>

By combining terms, we determine the closed-loop gain Template:Math: <math display="block">A_\text{CL} = \frac{V_\text{out}}{V_\text{in}} = 1 + \frac{R_\text{f}}{R_\text{g}}.</math>

Characteristics Template:Anchor

Ideal op amps

An ideal op amp is usually considered to have the following characteristics:<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

- Infinite open-loop gain Template:Math

- Infinite input impedance Template:Math, and so zero input current

- Zero input offset voltage

- Infinite output voltage range

- Infinite bandwidth with zero phase shift and infinite slew rate

- Zero output impedance Template:Math, and so infinite output current range

- Zero noise

- Infinite common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR)

- Infinite power supply rejection ratio.

These ideals can be summarized by the two Template:Em:

- In a closed loop the output does whatever is necessary to make the voltage difference between the inputs zero.

- The inputs draw zero current.<ref name=AoE>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Rp

The first rule only applies in the usual case where the op amp is used in a closed-loop design (negative feedback, where there is a signal path of some sort feeding back from the output to the inverting input). These rules are commonly used as a good first approximation for analyzing or designing op-amp circuits.<ref name="AoE"/>Template:Rp

None of these ideals can be perfectly realized. A real op amp may be modeled with non-infinite or non-zero parameters using equivalent resistors and capacitors in the op-amp model. The designer can then include these effects into the overall performance of the final circuit. Some parameters may turn out to have negligible effect on the final design while others represent actual limitations of the final performance.

Real op amps

Real op amps differ from the ideal model in various aspects.

Template:Glossary begin Template:Term Template:Defn

Template:Term Template:Defn Template:Glossary end

Non-linear imperfections

Template:Glossary begin Template:Term Template:Defn

Template:Term Template:Defn Template:Glossary end

Power considerations

Template:Glossary begin Template:Term Template:Defn

Template:Term Template:Defn Template:Glossary end

Classification

Op amps may be classified by their construction:

- discrete, built from individual transistors or tubes/valves,

- hybrid, consisting of discrete and integrated components,

- full integrated circuits — most common, having displaced the former two due to low cost.

IC op amps may be classified in many ways, including:

- Device grade, including acceptable operating temperature ranges and other environmental or quality factors. For example: LM101, LM201, and LM301 refer to the military, industrial, and commercial versions of the same component. Military and industrial-grade components offer better performance in harsh conditions than their commercial counterparts but are sold at higher prices.

- Classification by package type may also affect environmental hardiness, as well as manufacturing options; DIP, and other through-hole packages are tending to be replaced by surface-mount devices.

- Classification by internal compensation: op amps may suffer from high frequency instability in some negative feedback circuits unless a small compensation capacitor modifies the phase and frequency responses. Op amps with a built-in capacitor are termed compensated, and allow circuits above some specified closed-loop gain to be stable with no external capacitor. In particular, op amps that are stable even with a closed loop gain of 1 are called unity gain compensated.

- Single, dual and quad versions of many commercial op-amp IC are available, meaning 1, 2 or 4 operational amplifiers are included in the same package.

- Rail-to-rail input (and/or output) op amps can work with input (and/or output) signals very close to the power supply rails.<ref name="rail-to-rail" />

- CMOS op amps (such as the CA3140E) provide extremely high input resistances, higher than JFET-input op amps, which are normally higher than bipolar-input op amps.

- Programmable op amps allow the quiescent current, bandwidth and so on to be adjusted by an external resistor.

- Manufacturers often market their op amps according to purpose, such as low-noise pre-amplifiers, wide bandwidth amplifiers, and so on.

Applications

Historical timeline

1941: A vacuum tube op amp. An op amp, defined as a general-purpose, DC-coupled, high-gain, inverting feedback amplifier, is first found in Template:US patent "Summing Amplifier" filed by Karl D. Swartzel Jr. of Bell Labs in 1941. This design used three vacuum tubes to achieve a gain of Template:Nowrap and operated on voltage rails of Template:Nowrap. It had a single inverting input rather than differential inverting and non-inverting inputs, as are common in today's op amps. Throughout World War II, Swartzel's design proved its value by being liberally used in the M9 artillery director designed at Bell Labs. This artillery director worked with the SCR-584 radar system to achieve extraordinary hit rates (near 90%) that would not have been possible otherwise.<ref name="Jung-2004">Template:Cite book</ref>

1947: An op amp with an explicit non-inverting input. In 1947, the operational amplifier was first formally defined and named in a paper by John R. Ragazzini of Columbia University.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> In this same paper a footnote mentioned an op-amp design by a student that would turn out to be quite significant. This op amp, designed by Loebe Julie, had two major innovations. Its input stage used a long-tailed triode pair with loads matched to reduce drift in the output and, far more importantly, it was the first op-amp design to have two inputs (one inverting, the other non-inverting). The differential input made a whole range of new functionality possible, but it would not be used for a long time due to the rise of the chopper-stabilized amplifier.<ref name="Jung-2004"/>

1949: A chopper-stabilized op amp. In 1949, Edwin A. Goldberg designed a chopper-stabilized op amp.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> This set-up uses a normal op amp with an additional AC amplifier that goes alongside the op amp. The chopper gets an AC signal from DC by switching between the DC voltage and ground at a fast rate (60 or 400 Hz). This signal is then amplified, rectified, filtered and fed into the op amp's non-inverting input. This vastly improved the gain of the op amp while significantly reducing the output drift and DC offset. Unfortunately, any design that used a chopper couldn't use the non-inverting input for any other purpose. Nevertheless, the much-improved characteristics of the chopper-stabilized op amp made it the dominant way to use op amps. Techniques that used the non-inverting input were not widely practiced until the 1960s when op-amp ICs became available.

1953: A commercially available op amp. In 1953, vacuum tube op amps became commercially available with the release of the model K2-W from George A. Philbrick Researches, Incorporated. The designation on the devices shown, GAP/R, is an acronym for the complete company name. Two nine-pin 12AX7 vacuum tubes were mounted in an octal package and had a model K2-P chopper add-on available. This op amp was based on a descendant of Loebe Julie's 1947 design and, along with its successors, would start the widespread use of op amps in industry.<ref>Template:Citation</ref>

1961: A discrete IC op amp. With the birth of the transistor in 1947, and the silicon transistor in 1954, the concept of ICs became a reality. The introduction of the planar process in 1959 made transistors and ICs stable enough to be commercially useful. By 1961, solid-state, discrete op amps were being produced. These op amps were effectively small circuit boards with packages such as edge connectors. They usually had hand-selected resistors in order to improve things such as voltage offset and drift. The P45 (1961) had a gain of 94 dB and ran on ±15 V rails. It was intended to deal with signals in the range of Template:Nowrap.

1961: A varactor bridge op amp. There have been many different directions taken in op-amp design. Varactor bridge op amps started to be produced in the early 1960s.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>June 1961 advertisement for Philbrick P2, Template:Cite web</ref> They were designed to have extremely small input current and are still amongst the best op amps available in terms of common-mode rejection with the ability to correctly deal with hundreds of volts at their inputs.

1962: An op amp in a potted module. By 1962, several companies were producing modular potted packages that could be plugged into printed circuit boards.Template:Citation needed These packages were crucially important as they made the operational amplifier into a single black box which could be easily treated as a component in a larger circuit.

1963: A monolithic IC op amp. In 1963, the first monolithic IC op amp, the μA702 designed by Bob Widlar at Fairchild Semiconductor, was released. Monolithic ICs consist of a single chip as opposed to a chip and discrete parts (a discrete IC) or multiple chips bonded and connected on a circuit board (a hybrid IC). Almost all modern op amps are monolithic ICs; however, this first IC did not meet with much success. Issues such as an uneven supply voltage, low gain and a small dynamic range held off the dominance of monolithic op amps until 1965 when the μA709<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> (also designed by Bob Widlar) was released.

1968: Release of the μA741. The popularity of monolithic op amps was further improved with the release of the LM101 in 1967, which solved a variety of issues, and the subsequent release of the μA741 in 1968. The μA741 was extremely similar to the LM101 except that Fairchild's manufacturing processes allowed them to include a 30 pF compensation capacitor inside the chip instead of requiring external compensation. This simple difference has made the 741 a canonical op amp and a range of modern amps base their pinout on the 741s. The μA741 is still in production, and has become ubiquitous in electronics—many manufacturers produce a version of this classic chip, recognizable by part numbers containing 741.

1970: First high-speed, low-input current FET design. In the 1970s high-speed, low-input current designs started to be made by using FETs. These would be largely replaced by op amps made with MOSFETs in the 1980s.

1972: Single-sided supply op amps being produced. A single-sided supply op amp is one where the input and output voltages can be as low as the negative power supply voltage instead of needing to be at least two volts above it. The result is that it can operate in many applications with the negative supply pin on the op amp being connected to the signal ground, thus eliminating the need for a separate negative power supply. The LM324, released in 1972, was one such op amp that came in a quad package (four separate op amps in one package) and became an industry standard.

Recent trends. Supply voltages in analog circuits have decreased (as they have in digital logic) and low-voltage op amps have been introduced reflecting this. Supplies of 5 V and increasingly 3.3 V (sometimes as low as 1.8 V) are common. To maximize the signal range, modern op amps commonly have rail-to-rail output (the output signal can range from the lowest supply voltage to the highest) and sometimes rail-to-rail inputs.<ref name="rail-to-rail" />

See also

- µA741

- Current conveyor

- Template:Slink

- List of LM-series integrated circuits

- Operational transconductance amplifier

- Sallen–Key topology

Notes

References

Further reading

- Books

- Op Amps For Everyone; 5th Ed; Bruce Carter, Ron Mancini; Newnes; 484 pages; 2017; Template:ISBN. (2 MB PDF - 1st edition)

- Operational Amplifiers - Theory and Design; 3rd Ed; Johan Huijsing; Springer; 423 pages; 2017; Template:ISBN.

- Operational Amplifiers and Linear Integrated Circuits - Theory and Application; 3rd Ed; James Fiore; Creative Commons; 589 pages; 2016.(13 MB PDF Text)(2 MB PDF Lab)

- Analysis and Design of Linear Circuits; 8th Ed; Roland Thomas, Albert Rosa, Gregory Toussaint; Wiley; 912 pages; 2016; Template:ISBN.

- Design with Operational Amplifiers and Analog Integrated Circuits; 4th Ed; Sergio Franco; McGraw Hill; 672 pages; 2015; Template:ISBN.

- Small Signal Audio Design; 2nd Ed; Douglas Self; Focal Press; 780 pages; 2014; Template:ISBN.

- Linear Circuit Design Handbook; 1st Ed; Hank Zumbahlen; Newnes; 960 pages; 2008; Template:ISBN. (35 MB PDF)

- Op Amp Applications Handbook; 1st Ed; Walt Jung; Analog Devices & Newnes; 896 pages; 2005; Template:ISBN. (17 MB PDF)

- Operational Amplifiers and Linear Integrated Circuits; 6th Ed; Robert Coughlin, Frederick Driscoll; Prentice Hall; 529 pages; 2001; Template:ISBN.

- Active-Filter Cookbook; 2nd Ed; Don Lancaster; Sams; 240 pages; 1996; Template:ISBN. (28 MB PDF - 1st edition)

- IC Op-Amp Cookbook; 3rd Ed; Walt Jung; Prentice Hall; 433 pages; 1986; Template:ISBN. (18 MB PDF - 1st edition)

- Engineer's Mini-Notebook – OpAmp IC Circuits; 1st Ed; Forrest Mims III; Radio Shack; 49 pages; 1985; ASIN B000DZG196. (4 MB PDF)

- Template:Cite book

- Designing with Operational Amplifiers - Applications Alternatives; 1st Ed; Jerald Graeme; Burr-Brown & McGraw Hill; 269 pages; 1976; Template:ISBN.

- Applications of Operational Amplifiers - Third Generation Techniques; 1st Ed; Jerald Graeme; Burr-Brown & McGraw Hill; 233 pages; 1973; Template:ISBN. (37 MB PDF)

- Understanding IC Operational Amplifiers; 1st Ed; Roger Melen and Harry Garland; Sams Publishing; 128 pages; 1971; Template:ISBN. (archive)

- Operational Amplifiers - Design and Applications; 1st Ed; Jerald Graeme, Gene Tobey, Lawrence Huelsman; Burr-Brown & McGraw Hill; 473 pages; 1971; Template:ISBN.

- Books with opamp chapters

- Learning the Art of Electronics - A Hands-On Lab Course; 1st Ed; Thomas Hayes, Paul Horowitz; Cambridge; 1150 pages; 2016; Template:ISBN. (Part 3 is 268 pages)

- The Art of Electronics; 3rd Ed; Paul Horowitz, Winfield Hill; Cambridge; 1220 pages; 2015; Template:ISBN. (Chapter 4 is 69 pages)

- Lessons in Electric Circuits - Volume III - Semiconductors; 5th Ed; Tony Kuphaldt; Open Book Project; 528 page; 2009. (Chapter 8 is 59 pages) (4 MB PDF)

- Troubleshooting Analog Circuits; 1st Ed; Bob Pease; Newnes; 217 pages; 1991; Template:ISBN. (Chapter 8 is 19 pages)

- Historical application handbooks

- Analog Applications Manual (1979, 418 pages), Signetics. (OpAmps in section 3)

- Historical databooks

- Linear Databook 1 (1988, 1262 pages), National Semiconductor. (OpAmps in section 2)

- Linear and Interface Databook (1990, 1658 pages), Motorola. (OpAmps in section 2)

- Linear Databook (1986, 568 pages), RCA.

- Historical datasheets

- LM301, Single BJT OpAmp, Texas Instruments

- LM324, Quad BJT OpAmp, Texas Instruments

- LM741, Single BJT OpAmp, Texas Instruments

- NE5532, Dual BJT OpAmp, Texas Instruments (NE5534 is similar single)

- TL072, Dual JFET OpAmp, Texas Instruments (TL074 is Quad)

External links

Template:Commons category Template:Wikiversity Template:Wikibooks

- Op Amp Circuit Collection- National Semiconductor Corporation

- Operational Amplifiers - Chapter on All About Circuits

- Loop Gain and its Effects on Analog Circuit Performance - Introduction to loop gain, gain and phase margin, loop stability

- Simple Op Amp Measurements Template:Webarchive How to measure offset voltage, offset and bias current, gain, CMRR, and PSRR.

- Operational Amplifiers. Introductory on-line text by E. J. Mastascusa (Bucknell University).

- Introduction to op-amp circuit stages, second order filters, single op-amp bandpass filters, and a simple intercom

- MOS op amp design: A tutorial overview

- Operational Amplifier Noise Prediction (All Op Amps) using spot noise

- Operational Amplifier Basics Template:Webarchive

- History of the Op-amp Template:Webarchive, from vacuum tubes to about 2002

- Loebe Julie historical OpAmp interview by Bob Pease

- www.PhilbrickArchive.org Template:Spaced ndashA free repository of materials from George A Philbrick / Researches - Operational Amplifier Pioneer

- What's The Difference Between Operational Amplifiers And Instrumentation Amplifiers? Template:Webarchive, Electronic Design Magazine