Philistinism

Template:Short description {{#invoke:other uses|otheruses}}

In the fields of philosophy and of aesthetics, the term philistinism describes the attitudes, habits, and characteristics of a person who deprecates art, beauty, spirituality, and intellect.<ref name="Unabridged 1951">Webster's New Twentieth Century Dictionary of the English Language – Unabridged (1951) p. 1260</ref> As a derogatory term, philistine describes a person who is narrow-minded and hostile to the life of the mind, whose materialistic and wealth-oriented worldview and tastes indicate an indifference to cultural and aesthetic values.<ref>College Edition: Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language (1962) p. 1099</ref>

The contemporary meaning of philistine derives from Matthew Arnold's adaptation to English of the German word Philister, as applied by university students in their antagonistic relations with the townspeople of Jena, early modern Germany, where a riot resulted in several deaths in 1689. Preaching about the riot, Georg Heinrich Götze, the ecclesiastical superintendent, applied the word Philister in his sermon analysing the social class hostilities between students and townspeople.<ref name="Vulpius1818">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="Kluge2012">Template:Cite book</ref> Götze addressed the town-vs-gown matter with an admonishing sermon, "The Philistines Be Upon Thee", drawn from the Book of Judges (Chapt. Template:Bibleverse, Samson vs the Philistines), of the Old Testament.<ref>Benét's Reader's Encyclopedia Third Edition (1987) p. 759</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

History

In German usage, university students applied the term Philister (Philistine) to describe a person who was not trained at university; in the social context of early modern Germany, the term identified the man (Philister) and woman (Philisterin) who was not from the university.<ref name="Unabridged 1951"/>

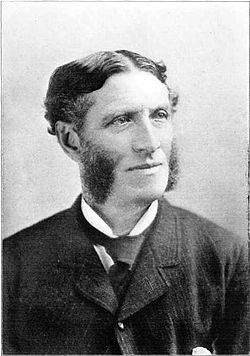

In Britain, the term philistine—a person hostile to aesthetic and intellectual discourse—was in common use by the 1820s, and was applied to the bourgeois, materialistic, merchant middle class of the Victorian Era (1837–1901), whose newly acquired social status and wealth rendered some of them hostile to cultural traditions which favored aristocratic power. Regarding the philistines, Matthew Arnold wrote in Culture and Anarchy: An Essay in Political and Social Criticism (1869):

Usages

The denotations and connotations of the terms philistinism and philistine describe people who are hostile to art, culture, and the life of the mind, and, in their stead, favor economic materialism and conspicuous consumption as paramount human activities.<ref>The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993), Lesley Brown, Ed., p. 2,186</ref>

17th century

Whilst involved in a lawsuit, the writer and poet Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), in the slang of his time, described a gruff bailiff as a philistine, someone who is considered a merciless enemy.<ref name="Unabridged 1951"/>

18th century

The polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) described the philistine personality, by asking:

Goethe described such men and women, by noting that:

In the comedy of manners play, The Rivals (1775), Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751–1816) identifies a violent aristocrat as 'that bloodthirsty Philistine, Sir Lucius O'Trigger'.

19th century

Thomas Carlyle often wrote of gigs and "gigmanity" as a sign of classist materialism; Arnold recognized Carlyle's use of the term as being synonymous with philistine. Carlyle used "philistine" to describe William Taylor in 1831. He also used it in Sartor Resartus (1833–34) and in The Life of John Sterling (1851), remembering conversations where "Philistines would enter, what we call bores, dullards, Children of Darkness".<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

The composer Robert Schumann (1810-1856) created Davidsbündler, a fictional society whose purpose is to fight the philistines. This fight appears in some of his musical pieces, such as Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6, and the concluding part of his Carnaval, op. 9, which is titled "Marche des Davidsbündler contre les Philistins".

In The Sickness Unto Death (1849), the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard criticises the spiritlessness of the philistine-bourgeois mentality of triviality and the self-deception of despair.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) identified the philistine as a person who, for a lack of true cultural unity, can only define style in the negative and through cultural conformity. The essay "David Strauss: the Confessor and the Writer" in Untimely Meditations is an extended critique of nineteenth-century German Philistinism.

20th century

- In the novel Der Ewige Spießer (The Eternal Philistine, 1930), the Austro–Hungarian writer Ödön von Horváth (1901–38) derided the cultural coarseness of the philistine man and his limited view of the world. The eponymous philistine is a failed businessman, a salesman of used cars, who aspires to the high-life of wealth; to realise that aspiration, he seeks to meet a rich woman who will support him, and so embarks upon a rail journey from Munich to Barcelona to seek her at the World's Fair.

- In the Lectures on Russian Literature (1981), in the essay 'Philistines and Philistinism' the writer Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977) describes the philistine man and woman as:

- In the Lectures on Literature (1982), in speaking of the novel Madame Bovary (1856), about the bourgeois wife of a country doctor, Nabokov said that philistinism is manifest in the prudish attitude demonstrated by the man or the woman who accuses a work of art of being obscene.<ref>Nabokov, Lectures on Literature, lecture on Madame Bovary</ref>