Raised beach

Template:Short description Template:Redirect

A raised beach, coastal terrace,<ref name="Pinter2010">Pinter, N (2010): 'Coastal Terraces, Sealevel, and Active Tectonics' (educational exercise), from Template:Cite web [02/04/2011]</ref> or perched coastline is a relatively flat, horizontal or gently inclined surface of marine origin,<ref name="Pirazzoli2005a">Pirazzoli, PA (2005a): 'Marine Terraces', in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 632–633</ref> mostly an old abrasion platform which has been lifted out of the sphere of wave activity (sometimes called "tread"). Thus, it lies above or under the current sea level, depending on the time of its formation.<ref name="Strahler2005">Strahler AH; Strahler AN (2005): Physische Geographie. Ulmer, Stuttgart, 686 p.</ref><ref name="Leser2005">Leser, H (ed)(2005): ‚Wörterbuch Allgemeine Geographie. Westermann&Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Braunschweig, 1119 p.</ref> It is bounded by a steeper ascending slope on the landward side and a steeper descending slope on the seaward side<ref name="Pirazzoli2005a" /> (sometimes called "riser"). Due to its generally flat shape, it is often used for anthropogenic structures such as settlements and infrastructure.<ref name="Strahler2005" />

A raised beach is an emergent coastal landform. Raised beaches and marine terraces are beaches or wave-cut platforms raised above the shoreline by a relative fall in the sea level.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Around the world, a combination of tectonic coastal uplift and Quaternary sea-level fluctuations has resulted in the formation of marine terrace sequences, most of which were formed during separate interglacial highstands that can be correlated to marine isotope stages (MIS).<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

A marine terrace commonly retains a shoreline angle or inner edge, the slope inflection between the marine abrasion platform and the associated paleo sea cliff. The shoreline angle represents the maximum shoreline of a transgression and therefore a paleo-sea level.

Morphology

The platform of a marine terrace usually has a gradient between 1°Template:Ndash5° depending on the former tidal range with, commonly, a linear to concave profile. The width is quite variable, reaching up to Template:Convert, and seems to differ between the northern and southern hemispheres.<ref name="pethic1984">Pethick, J (1984): An Introduction to Coastal Geomorphology. Arnold&Chapman&Hall, New York, 260p.</ref> The cliff faces that delimit the platform can vary in steepness depending on the relative roles of marine and subaerial processes.<ref name="Masselink2003">Masselink, G; Hughes, MG (2003): Introduction to Coastal Processes & Geomorphology. Arnold&Oxford University Press Inc., London, 354p.</ref> At the intersection of the former shore (wave-cut/abrasion-) platform and the rising cliff face the platform commonly retains a shoreline angle or inner edge (notch) that indicates the location of the shoreline at the time of maximum sea ingression and therefore a paleo-sea level.<ref name="Cantalamessa2003">Template:Cite journal</ref> Sub-horizontal platforms usually terminate in a low-tide cliff, and it is believed that the occurrence of these platforms depends on the tidal activity.<ref name="Masselink2003" /> Marine terraces can extend for several tens of kilometers parallel to the coast.<ref name="Strahler2005" />

Older terraces are covered by marine and/or alluvial or colluvial materials while the uppermost terrace levels usually are less well preserved.<ref name="Ota1991">Template:Cite journal</ref> While marine terraces in areas of relatively rapid uplift rates (> 1 mm/year) can often be correlated to individual interglacial periods or stages, those in areas of slower uplift rates may have a polycyclic origin with stages of returning sea levels following periods of exposure to weathering.<ref name="Pirazzoli2005a" />

Marine terraces can be covered by a wide variety of soils with complex histories and different ages. In protected areas, allochthonous sandy parent materials from tsunami deposits may be found. Common soil types found on marine terraces include planosols and solonetz.<ref name="Finkl2005">Finkl, CW (2005): 'Coastal Soils' in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 278–302</ref>

Formation

It is now widely thought that marine terraces are formed during the separated high stands of interglacial stages correlated to marine isotope stages (MIS).<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Bull, W.B., 1985. Correlation of flights of global marine terraces. In: Morisawa M. & Hack J. (Editor), 15th Annual Geomorphology Symposium. Hemel Hempstead, State University of New York at Binghamton, pp. 129–152.</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Causes

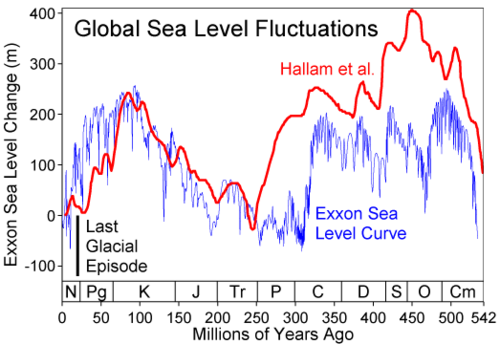

The formation of marine terraces is controlled by changes in environmental conditions and by tectonic activity during recent geological times. Changes in climatic conditions have led to eustatic sea-level oscillations and isostatic movements of the Earth's crust, especially with the changes between glacial and interglacial periods.

Processes of eustasy lead to glacioeustatic sea level fluctuations due to changes in the water volume in the oceans, and hence to regressions and transgressions of the shoreline. At times of maximum glacial extent during the last glacial period, the sea level was about Template:Convert lower compared to today. Eustatic sea level changes can also be caused by changes in the void volume of the oceans, either through sedimento-eustasy or tectono-eustasy.<ref name="Ahnert1996">Ahnert, F (1996) – Einführung in die Geomorphologie. Ulmer, Stuttgart, 440 p.</ref>

Processes of isostasy involve the uplift of continental crusts along with their shorelines. Today, the process of glacial isostatic adjustment mainly applies to Pleistocene glaciated areas.<ref name="Ahnert1996" /> In Scandinavia, for instance, the present rate of uplift reaches up to Template:Convert/year.<ref name="Lehmkuhl2007">Lehmkuhl, F; Römer, W (2007): 'Formenbildung durch endogene Prozesse: Neotektonik', in Gebhardt, H; Glaser, R; Radtke, U; Reuber, P (ed) Geographie, Physische Geographie und Humangeographie. Elsevier, München, pp. 316–320</ref>

In general, eustatic marine terraces were formed during separate sea-level highstands of interglacial stages<ref name="Ahnert1996" /><ref name="James1971">Template:Cite journal</ref> and can be correlated to marine oxygen isotopic stages (MIS).<ref name="Johnson1997">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Muhs1990">Template:Cite journal</ref> Glacioisostatic marine terraces were mainly created during stillstands of the isostatic uplift.<ref name="Ahnert1996" /> When eustasy was the main factor for the formation of marine terraces, derived sea level fluctuations can indicate former climate changes. This conclusion has to be treated with care, as isostatic adjustments and tectonic activities can be extensively overcompensated by an eustatic sea level rise. Thus, in areas of both eustatic and isostatic or tectonic influences, the course of the relative sea level curve can be complicated.<ref name="Worsley1998">Worsley, P (1998): 'Altersbestimmung – Küstenterrassen', in Goudie, AS (ed) Geomorphologie, Ein Methodenhandbuch für Studium und Praxis. Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 528–550</ref> Hence, most of today's marine terrace sequences were formed by a combination of tectonic coastal uplift and Quaternary sea level fluctuations.

Jerky tectonic uplifts can also lead to marked terrace steps while smooth relative sea level changes may not result in obvious terraces, and their formations are often not referred to as marine terraces.<ref name="Cantalamessa2003" />

Processes

Marine terraces often result from marine erosion along rocky coastlines<ref name="Pirazzoli2005a" /> in temperate regions due to wave attacks and sediment carried in the waves. Erosion also takes place in connection with weathering and cavitation. The speed of erosion is highly dependent on the shoreline material (hardness of rock<ref name="Masselink2003" />), the bathymetry, and the bedrock properties and can be between only a few millimeters per year for granitic rocks and more than Template:Convert per year for volcanic ejecta.<ref name="Masselink2003" /><ref name="Anderson1999">Template:Cite journal</ref> The retreat of the sea cliff generates a shore (wave-cut/abrasion-) platform through the process of abrasion. A relative change in the sea level leads to regressions or transgressions and eventually forms another terrace (marine-cut terrace) at a different altitude, while notches in the cliff face indicate short stillstands.<ref name="Anderson1999" />

It is believed that the terrace gradient increases with tidal range and decreases with rock resistance. In addition, the relationship between terrace width and the strength of the rock is inverse, and higher rates of uplift and subsidence as well as a higher slope of the hinterland increase the number of terraces formed during a certain time.<ref name="Trenhaile2002">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Furthermore, shore platforms are formed by denudation and marine-built terraces arise from accumulations of materials removed by shore erosion.<ref name="Pirazzoli2005a" /> Thus, a marine terrace can be formed by both erosion and accumulation. However, there is an ongoing debate about the roles of wave erosion and weathering in the formation of shore platforms.<ref name="Masselink2003" />

Reef flats or uplifted coral reefs are another kind of marine terrace found in intertropical regions. They are a result of biological activity, shoreline advance and accumulation of reef materials.<ref name="Pirazzoli2005a" />

While a terrace sequence can date back hundreds of thousands of years, its degradation is a rather fast process. A deeper transgression of cliffs into the shoreline may destroy previous terraces; but older terraces might be decayed<ref name="Anderson1999" /> or covered by deposits, colluvia or alluvial fans.<ref name="Strahler2005" /> Erosion and backwearing of slopes caused by incisive streams play another important role in this degradation process.<ref name="Anderson1999" />

Land and sea level history

The total displacement of the shoreline relative to the age of the associated interglacial stage allows the calculation of a mean uplift rate or the calculation of eustatic level at a particular time if the uplift is known.

To estimate vertical uplift, the eustatic position of the considered paleo sea levels relative to the present one must be known as precisely as possible. Current chronology relies principally on relative dating based on geomorphologic criteria, but in all cases, the shoreline angle of the marine terraces is associated with numerical ages. The best-represented terrace worldwide is the one correlated to the last interglacial maximum (MIS 5e).<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The age of MISS 5e is arbitrarily fixed to range from 130 to 116 ka<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> but is demonstrated to range from 134 to 113 ka in Hawaii and Barbados with a peak from 128 to 116 ka on tectonically stable coastlines. Older marine terraces well represented in worldwide sequences are those related to MIS 9 (~303–339 ka) and 11 (~362–423 ka).<ref>Imbrie, J. et al., 1984. The orbital theory of Pleistocene climate: support from revised chronology of the marine 18O record. In: A. Berger, J. Imbrie, J.D. Hays, G. Kukla and B. Saltzman (Editors), Milankovitch and Climate. Reidel, Dordrecht, pp. 269–305.</ref> Compilations show that sea level was 3 ± 3 meters higher during MIS 5e, MIS 9 and 11 than during the present one and −1 ± 1 m to the present one during MIS 7.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Consequently, MIS 7 (~180-240 ka) marine terraces are less pronounced and sometimes absent. When the elevations of these terraces are higher than the uncertainties in paleo-eustatic sea level mentioned for the Holocene and Late Pleistocene, these uncertainties don't affect on overall interpretation.

The sequence can also occur where the accumulation of ice sheets has depressed the land so that when the ice sheets melt the land readjusts with time thus raising the height of the beaches (glacial-isostatic rebound) and in places where co-seismic uplift occurs. In the latter case, the terrace is not correlated with sea-level highstands even if co-seismic terraces are known only for the Holocene.

Mapping and surveying

For exact interpretations of the morphology, extensive datings, surveying and mapping of marine terraces are applied. This includes stereoscopic aerial photographic interpretation (ca. 1 : 10,000 – 25,000<ref name="Cantalamessa2003" />), on-site inspections with topographic maps (ca. 1 : 10,000) and analysis of eroded and accumulated material. Moreover, the exact altitude can be determined with an aneroid barometer or preferably with a levelling instrument mounted on a tripod. It should be measured with an accuracy of Template:Convert and at about every Template:Convert, depending on the topography. In remote areas, the techniques of photogrammetry and tacheometry can be applied.<ref name="Worsley1998" />

Correlation and dating

Different methods for dating and correlation of marine terraces can be used and combined.

Correlational dating

The morphostratigraphic approach focuses especially in regions of marine regression on the altitude as the most important criterion to distinguish coastlines of different ages. Moreover, individual marine terraces can be correlated based on their size and continuity. Also, paleo-soils as well as glacial, fluvial, eolian and periglacial landforms and sediments may be used to find correlations between terraces.<ref name="Worsley1998" /> On New Zealand's North Island, for instance, tephra and loess were used to date and correlate marine terraces.<ref name="Berryman1992">Template:Cite journal</ref> At the terminus advance of former glaciers marine terraces can be correlated by their size, as their width decreases with age due to the slowly thawing glaciers along the coastline.<ref name="Worsley1998" />

The lithostratigraphic approach uses typical sequences of sediment and rock strata to prove sea-level fluctuations based on an alternation of terrestrial and marine sediments or littoral and shallow marine sediments. Those strata show typical layers of transgressive and regressive patterns.<ref name="Worsley1998" /> However, an unconformity in the sediment sequence might make this analysis difficult.<ref name="Bhattacharya2011">Template:Cite journal</ref>

The biostratigraphic approach uses remains of organisms which can indicate the age of a marine terrace. For that, often mollusc shells, foraminifera or pollen are used. Especially Mollusca can show specific properties depending on their depth of sedimentation. Thus, they can be used to estimate former water depths.<ref name="Worsley1998" />

Marine terraces are often correlated to marine oxygen isotopic stages (MIS)<ref name="Johnson1997" /> and can also be roughly dated using their stratigraphic position.<ref name="Worsley1998" />

Direct dating

There are various methods for the direct dating of marine terraces and their related materials. The most common method is 14C radiocarbon dating,<ref name="Schellmann2005">Schellmann, G; Brückner, H (2005): 'Geochronology', in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 467–472</ref> which has been used, for example, on the North Island of New Zealand to date several marine terraces.<ref name="Ota1992">Template:Cite journal</ref> It utilizes terrestrial biogenic materials in coastal sediments, such as mollusc shells, by analyzing the 14C isotope.<ref name="Worsley1998" /> In some cases, however, dating based on the 230Th/234U ratio was applied, in case detrital contamination or low uranium concentrations made finding a high-resolution dating difficult.<ref name="Garnett2003">Template:Cite journal</ref> In a study in southern Italy, paleomagnetism was used to carry out paleomagnetic datings<ref name="Brückner1980">Brückner, H (1980): 'Marine Terrassen in Süditalien. Eine quartärmorphologische Studie über das Küstentiefland von Metapont', Düsseldorfer Geographische Schriften, 14, Düsseldorf, Germany: Düsseldorf University</ref> and luminescence dating (OSL) was used in different studies on the San Andreas Fault<ref name="Grove2010">Template:Cite journal</ref> and on the Quaternary Eupcheon Fault in South Korea.<ref name="Kim2011">Template:Cite journal</ref> In the last decade, the dating of marine terraces has been enhanced since the arrival of the terrestrial cosmogenic nuclides method, particularly through the use of 10Be and 26Al cosmogenic isotopes produced on site.<ref name="Perg2001">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Kim2004">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Saillard2009">Template:Cite journal</ref> These isotopes record the duration of surface exposure to cosmic rays.<ref name="GossePhillips2001">Template:Cite journal</ref> This exposure age reflects the age of abandonment of a marine terrace by the sea.

To calculate the eustatic sea level for each dated terrace, it is assumed that the eustatic sea-level position corresponding to at least one marine terrace is known and that the uplift rate has remained essentially constant in each section.<ref name="Pirazzoli2005a" />

Relevance for other research areas

Marine terraces play an important role in the research on tectonics and earthquakes. They may show patterns and rates of tectonic uplift<ref name="Grove2010" /><ref name="Saillard2009" /><ref name="Saillard2011">Template:Cite journal</ref> and thus may be used to estimate the tectonic activity in a certain region.<ref name="Kim2011" /> In some cases the exposed secondary landforms can be correlated with known seismic events such as the 1855 Wairarapa earthquake on the Wairarapa Fault near Wellington, New Zealand which produced a Template:Convert uplift.<ref name="Crozier2010">Crozier, MJ; Preston NJ (2010): 'Wellington's Tectonic Landscape: Astride a Plate Boundary' in Migoń, P. (ed) Geomorphological Landscapes of the World. Springer, New York, pp. 341–348</ref> This figure can be estimated from the vertical offset between raised shorelines in the area.<ref name="McSaveney2006">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Furthermore, with the knowledge of eustatic sea level fluctuations, the speed of isostatic uplift can be estimated<ref name="Press2008">Press, F; Siever, R (2008): Allgemeine Geologie. Spektrum&Springer, Heidelberg, 735 p.</ref> and eventually the change of relative sea levels for certain regions can be reconstructed. Thus, marine terraces also provide information for the research on climate change and trends in future sea level changes.<ref name="Masselink2003" /><ref name="Schellmann2007">Template:Cite journal</ref>

When analyzing the morphology of marine terraces, it must be considered, that both eustasy and isostasy can influence on the formation process. This way can be assessed, whether there were changes in sea level or whether tectonic activities took place.

Prominent examples

Raised beaches are found in a wide variety of coast and geodynamical backgrounds such as subduction on the Pacific coasts of South and North America, passive margin of the Atlantic coast of South America,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> collision context on the Pacific coast of Kamchatka, Papua New Guinea, New Zealand, Japan, passive margin of the South China Sea coast, on west-facing Atlantic coasts, such as Donegal Bay, County Cork and County Kerry in Ireland; Bude, Widemouth Bay, Crackington Haven, Tintagel, Perranporth and St Ives in Cornwall, the Vale of Glamorgan, Gower Peninsula, Pembrokeshire and Cardigan Bay in Wales, Jura and the Isle of Arran in Scotland, Finistère in Brittany and Galicia in Northern Spain and at Squally Point in Eatonville, Nova Scotia within the Cape Chignecto Provincial Park.

Other important sites include various coasts of New Zealand, e.g. Turakirae Head near Wellington being one of the world's best and most thoroughly studied examples.<ref name="Crozier2010" /><ref name="McSaveney2006" /><ref name="Wellman1969">Template:Cite journal</ref> Also along the Cook Strait in New Zealand, there is a well-defined sequence of uplifted marine terraces from the late Quaternary at Tongue Point. It features a well-preserved lower terrace from the last interglacial, a widely eroded higher terrace from the penultimate interglacial and another still higher terrace, which is nearly completely decayed.<ref name="Crozier2010" /> Furthermore, on New Zealand's North Island at the eastern Bay of Plenty, a sequence of seven marine terraces has been studied.<ref name="Ota1991" /><ref name="Ota1992" />

Along many coasts of the mainland and islands around the Pacific, marine terraces are typical coastal features. An especially prominent marine terraced coastline can be found north of Santa Cruz, near Davenport, California, where terraces probably have been raised by repeated slip earthquakes on the San Andreas Fault.<ref name="Grove2010" /><ref name="Pirazzoli2005b">Pirazzoli, PA (2005b.): 'Tectonics and Neotectonics', Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 941–948</ref> Hans Jenny famously researched the pygmy forests of the Mendocino and Sonoma county marine terraces. The marine terrace's "ecological staircase" of Salt Point State Park is also bound by the San Andreas Fault.

Along the coasts of South America marine terraces are present,<ref name="Saillard2009" /><ref name="Saillard2012">Template:Cite journal</ref> where the highest ones are situated where plate margins lie above subducted oceanic ridges and the highest and most rapid rates of uplift occur.<ref name="Goy1992">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Saillard2011" /> At Cape Laundi, Sumba Island, Indonesia an ancient patch reef can be found at Template:Convert above sea level as part of a sequence of coral reef terraces with eleven terraces being wider than Template:Convert.<ref name="Pirazzoli1991">Template:Cite journal</ref> The coral marine terraces at Huon Peninsula, New Guinea, which extend over Template:Convert and rise over Template:Convert above present sea level<ref name="Chappell1974">Template:Cite journal</ref> are currently on UNESCO's tentative list for world heritage sites under the name Houn Terraces - Stairway to the Past.<ref name="UNESCO2006">UNESCO (2006): Huon Terraces – Stairway to the Past. from https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5066/ [13/04/2011]</ref>

Other considerable examples include marine terraces rising to Template:Convert on some Philippine Islands<ref name="eisma2005">Eisma, D (2005): 'Asia, eastern, Coastal Geomorphology', in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 67–71</ref> and along the Mediterranean Coast of North Africa, especially in Tunisia, rising to Template:Convert.<ref name="Orme2005">Orme, AR (2005): 'Africa, Coastal Geomorphology', in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 9–21</ref>

Related coastal geography

Uplift can also be registered through tidal notch sequences. Notches are often portrayed as lying at sea level; however, notch types form a continuum from wave notches formed in quiet conditions at sea level to surf notches formed in more turbulent conditions and as much as Template:Convert above sea level.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> As stated above, there was at least one higher sea level during the Holocene, so some notches may not contain a tectonic component in their formation.

See also

- Similar features

- Beach erosion and accretion

- Coastal management, to prevent coastal erosion and creation of beach

- Erosion

- Longshore drift

References

External links

- Notes at NAHSTE

- US Geological Survey Marine Terrace Fact Sheet - Wikimedia link, USGS link