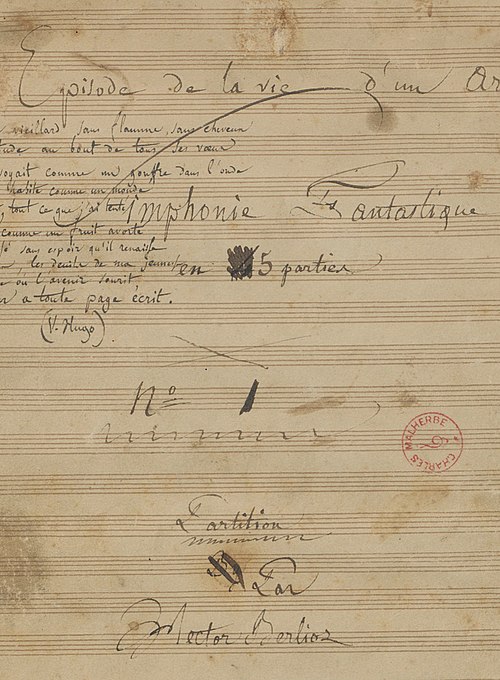

Symphonie fantastique

Template:Short description Template:Italic title Template:Infobox musical composition Template:Lang (Fantastic Symphony: Episode in the Life of an Artist … in Five Sections) Op. 14, is a programmatic symphony written by Hector Berlioz in 1830. The first performance was at the Paris Conservatoire on 5 December 1830.

Berlioz wrote semi-autobiographical programme notes for the piece that allude to the romantic sufferings of a gifted artist who has poisoned himself with opium because of his unrequited love for a beautiful and fascinating woman (in real life, the Shakespearean actress Harriet Smithson, who in 1833 became the composer's wife). The composer, who revered Beethoven, followed the latter's unusual addition in the Pastoral Symphony of a fifth movement to the normal four of a classical symphony. The artist's reveries take him to a ball and to a pastoral scene in a field, which is interrupted by a hallucinatory march to the scaffold, leading to a grotesque satanic dance (Witches' Sabbath). Within each episode, the artist's passion is represented by a recurring theme called the Template:Lang.

The symphony has long been a favourite with audiences and conductors. In 1831 Berlioz wrote a sequel, Lélio, for actor, soloists, chorus, piano and orchestra. Franz Liszt made a piano transcription of the score that was first recorded by Idil Biret in 1979.

Overview

The Template:Lang is a piece of programme music that tells the story of a gifted artist who, in the depths of hopelessness and despair because of his unrequited love for a woman, has poisoned himself with opium. The symphony tells the story of the artist's drug-fuelled hallucinations, beginning with a ball and a scene in a field and ending with a march to the scaffold and a satanic dream. The artist's passion is represented by an elusive theme which Berlioz called the idée fixe, a contemporary medical term also found in literary works of the period.<ref name=Brittan2006>Template:Cite journal</ref> It is defined by the Dictionnaire de l'Académie française as "an idea that keeps coming back to mind, an obsessive preoccupation".Template:Refn

Berlioz provided his own preface and programme notes for each movement of the work. They exist in two principal versions: one from 1845 in the first edition of the work and the second from 1855.<ref>Cone, pp. 20 and 30</ref> These changes show how Berlioz downplayed the programmatic aspect of the piece later in life.

The first printing of the score, dedicated to Nicholas I of Russia, was published in 1845.<ref>Macdonald, p. 46</ref> In it, Berlioz writes:<ref>Cone, p. 20; translation via Microsoft and Google</ref> Template:Blockquote

In 1855 Berlioz writes:<ref>Cone, p. 30; translation via Microsoft and Google</ref> Template:Blockquote

Berlioz wanted people to understand his compositional intention, as the story he attached to each movement drove his musical choices. He said, "For this reason I generally find it extremely painful to hear my works conducted by someone other than myself."<ref>O'Neal, p. 119</ref>

Inspiration

Attending a performance of Shakespeare's Hamlet on 11 September 1827, Berlioz fell in love with the Irish actress Harriet Smithson, who played the role of Ophelia. His biographer Hugh Macdonald writes of Berlioz's "emotional derangement" in obsessively pursuing her, without success, for several years. She refused even to meet him.<ref name=odnb>Bickley, Diana. "Berlioz, Louis Hector", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 Template:ODNBsub</ref><ref name=grove>Macdonald, Hugh."Berlioz, (Louis-)Hector", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001 Template:Subscription required</ref> He sent her numerous love letters, all of which were unanswered.<ref>Holoman (1989), p. 54</ref>

The Symphonie fantastique reflects his obsession with Smithson. She did not attend the premiere, given at the Paris Conservatoire on 5 December 1830, but she heard Berlioz's revised version of the work in 1832 at a concert that also included its sequel, Lélio, which incorporates the same idée fixe and some spoken commentary.<ref>Holoman (1989), p. 134</ref> She finally appreciated the strength of his feelings for her. The two met shortly afterwards and began a romance that led to their marriage the following year.<ref>Holoman (1989), pp. 136–137 and 151</ref>

Instrumentation

The score calls for an orchestra of about 90 players:

Template:Col-begin Template:Col-2

- Brass

- 4 horns

- 2 cornets

- 2 trumpets

- 3 trombones

- 2 ophicleidesTemplate:Refn

- cymbals

- snare drum (used only in movement IV)

- bass drum

- Template:Hanging indent

- at least 15 1st violins

- at least 15 2nd violins

- at least 10 violas

- at least 11 celli

- at least 9 double basses

Template:Col-2 Template:Col-end

Movements

Following the precedent of the Pastoral Symphony of Beethoven, whom Berlioz revered, the symphony has five movements, instead of four as was conventional for symphonies of the time.<ref>Cairns, p. 212</ref>

Each movement depicts an episode in the protagonist's life that is described by Berlioz in the notes to the 1845 score. These notes are quoted (in italics) in each section below.

I. "Rêveries – Passions" (Daydreams – passions)

Template:Listen Template:Blockquote Structurally the movement derives from the traditional sonata form found in all classical symphonies. A long, slow introduction leads to an Allegro in which Berlioz introduces the idée fixe as the main theme of a sonata form comprising a short exposition followed by alternating sections of development and recapitulation.<ref>Langford, p. 34</ref> The idée fixe begins:

The theme was taken from Berlioz's scène lyrique "Herminie", composed in 1828.<ref>Steinberg, p. 64</ref>

II. "Un bal" (A ball)

Template:Listen Template:Blockquote

The second movement is a waltz in Template:Music. It begins with a mysterious introduction that creates an atmosphere of impending excitement, followed by a passage dominated by two harps; then the flowing waltz theme appears, derived from the idée fixe at first,<ref name="caltech">Template:Cite web</ref> then transforming it. More formal statements of the idée fixe twice interrupt the waltz.

The movement is the only one to feature the two harps. Another feature of the movement is that Berlioz added a part for solo cornet to his autograph score, although it was not included in the score published in his lifetime. It is believed to have been written for the virtuoso cornet player Jean-Baptiste Arban.<ref>Holoman (2000), p. 177.</ref> The work has most often been played and recorded without the solo cornet part.<ref>The Hector Berlioz Website: Berlioz Music Scores. Retrieved 26 July 2014</ref>

III. "Scène aux champs" (Scene in the country)

Template:Listen Template:Blockquote

The third movement is a slow movement, marked Adagio, in Template:Music. The two shepherds mentioned in the programme notes are depicted by a cor anglais and an offstage oboe tossing an evocative melody back and forth. After the cor anglais–oboe conversation, the principal theme of the movement appears on solo flute and violins. It begins with:

Berlioz salvaged this theme from his abandoned Messe solennelle.<ref name=s65>Steinberg, p. 65</ref> The idée fixe returns in the middle of the movement, played by oboe and flute. The sound of distant thunder at the end of the movement is a striking passage for four timpani.<ref name=s65/>

IV. "Marche au supplice" (March to the scaffold)

Template:Listen Template:Blockquote

Berlioz claimed to have written the fourth movement in a single night, reconstructing music from an unfinished project, the opera Les francs-juges.<ref name=s65/> The movement begins with timpani sextuplets in thirds, for which he directs: "The first quaver of each half-bar is to be played with two drumsticks, and the other five with the right hand drumsticks". The movement proceeds as a march filled with blaring horns and rushing passages, and scurrying figures that later show up in the last movement.

Before the musical depiction of his execution, there is a brief, nostalgic recollection of the idée fixe in a solo clarinet part, as though representing the last conscious thought of the soon-to-be-executed man.<ref name=c24/>

V. "Songe d'une nuit du sabbat" (Dream of a night of the sabbath)

Template:Listen Template:Blockquote

This movement can be divided into sections according to tempo changes:

- The introduction is Largo, in common time, creating an ominous quality through the copious use of diminished seventh chords <ref>Hovland, E., “Who's afraid of Berlioz?”, Studia Musicologica Norvegica. Vol 45, No. 1, pp. 9-30.</ref> dynamic variations and instrumental effects, particularly in the strings (tremolos, pizzicato, sforzando).

- At bar 21, the tempo changes to Allegro and the metre to Template:Music. The return of the idée fixe as a "vulgar dance tune" is depicted by the C clarinet. This is interrupted by an Allegro Assai section in cut time at bar 29.

- The idée fixe then returns as a prominent [[E-flat clarinet|ETemplate:Music clarinet]] solo at bar 40, in Template:Music and Allegro. The ETemplate:Music clarinet contributes a brighter timbre than the C clarinet.

- At bar 80, there is one bar of alla breve, with descending crotchets in unison through the entire orchestra. Again in Template:Music, this section sees the introduction of the bells (or Piano playing in Triple Octaves) and fragments of the "witches' round dance".

- The "Dies irae" begins at bar 127, the motif derived from the 13th-century Latin sequence. It is initially stated in unison between the unusual combination of four bassoons and two ophicleides. The key, C minor, allows the bassoons to render the theme at the bottom of their range.

- At bar 222, the "witches' round dance" motif is repeatedly stated in the strings, to be interrupted by three syncopated notes in the brass. This leads into the Ronde du Sabbat (Sabbath Round) at bar 241, where the motif is finally expressed in full.

- The Dies irae et Ronde du Sabbat Ensemble section is at bar 414.

There are a host of effects, including trilling in the woodwinds and col legno in the strings. The climactic finale combines the somber Dies Irae melody, now in A minor, with the fugue of the Ronde du Sabbat, building to a modulation into ETemplate:Music major, then chromatically into C major, ending on a C chord.

Reception

At the premiere of the Template:Lang, there was protracted applause at the end, and the press reviews expressed both the shock and the pleasure the work had given.<ref>Barzun, p. 107</ref> There were dissenting voices, such as that of Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl, the conservative author of the Template:Lang, who regarded the work as an abomination for which Berlioz would suffer in Purgatory,<ref name="n273">Niecks, p. 273</ref> but despite the striking unconventionality of the work, it was generally well received. François-Joseph Fétis, founder of the influential Template:Lang wrote of it approvingly,<ref>Macdonald, p. 243</ref> and Robert Schumann published an extensive, and broadly supportive analysis of the piece in the Template:Lang in 1835.<ref name="n273" /> He had reservations about "wild and bizarre" elements and some of the harmonies,<ref>Schumann, p. 173</ref> but concluded: "in spite of an apparent formlessness, there is an inherent correct symmetrical order corresponding to the great dimensions of the work – and this besides the inner connection of thought".<ref>Schumann, p. 168</ref> When the work was played in New York in 1865 critical opinion was divided: "We think the Philharmonic Society wasted much valuable time in the vain endeavor to make Berlioz's fantastic ravings intelligible to a sane audience" (New York Tribune); a rare treat, "a wonderful creation" (New York Daily Herald).<ref>"Musical", New York Tribune, 29 January 1866, p. 5; and "Musical", New York Daily Herald, 31 December 1865, p. 4</ref>

By the middle of the 20th century, the authors of The Record Guide, calling the work "one of the most remarkable outbursts of genius in the history of music", commented that it was a favourite with the public and with great conductors.<ref>Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 120</ref> Opinions differed about how much the symphony fitted the classical symphonic model. Sir Thomas Beecham, a lifelong proponent of Berlioz's music, remarked on the originality of the work, which "broke upon the world like some unaccountable effort of spontaneous generation which had dispensed with the machinery of normal parentage".<ref>Beecham, p. 183</ref> A later conductor, Leonard Bernstein, said of the hallucinatory aspects of the work: "Berlioz tells it like it is ... You take a trip, you wind up screaming at your own funeral. Take a tip from Berlioz: that music is all you need for the wildest trip you can take, to hell and back."<ref>Bernstein, p. 337</ref> Others regard the work as more recognisably classical: Constant Lambert wrote of the symphony, "formally speaking it is among the finest of nineteenth century symphonies".<ref>Lambert, p. 144</ref> The composer and musical scholar Wilfrid Mellers called the symphony "ostensibly autobiographical, yet fundamentally classical ... Far from being romantic rhapsodizing held together only by an outmoded literary commentary, the Symphonie fantastique is one of the most tautly disciplined works in early nineteenth-century music."<ref name="m187">Mellers, p. 187</ref>

Use in modern times

The main title sequence from Stanley Kubrick's film The Shining released in 1980, was scored by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind. Within the title track is a reworking of the "Dies irae" section of Symphonie fantastique's fifth movement 'Songe D'une Nuit De Sabbat (Dreams of a Witches' Sabbath)'. <ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

The “Dies irae” traditional melody is translated from Latin as “day of wrath”. It is a somber chant dating back to the Middle Ages. The melody was originally used as part of funeral church services, usually as a sung mass for the dead. It has been used by composers to symbolise death, perhaps most prominently in Symphonie fantastique. <ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Notes, references and sources

Notes

References

Sources

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

External links

Template:Commons category Template:Wikiquote

- Symphonie fantastique on the Hector Berlioz Website, with links to Scorch full score and programme note written by the composer.

- Template:IMSLP

- Keeping Score: Berlioz Symphonie fantastique, multimedia website with interactive score produced by the San Francisco Symphony

- European Archive. A copyright-free LP recording of the Symphonie fantastique by Willem van Otterloo (conductor) and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra at the European Archive

- Beyond the Score. A concert-hall dramatized documentary and performance with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonie fantastique at the Internet Archive, performed by the Cleveland Orchestra, Artur Rodzinski conducting

- Complete performance of the symphony by the London Symphony Orchestra accompanied by visual illustrations of the symphony's programme

Template:Berlioz compositions Template:Portal bar Template:Authority control