Trapezoidal rule

Template:Short description Template:About

In calculus, the trapezoidal rule (informally trapezoid rule; or in British English trapezium rule)Template:Efn is a technique for numerical integration, i.e. approximating the definite integral: <math display="block">\int_a^b f(x) \, dx.</math>

The trapezoidal rule works by approximating the region under the graph of the function <math>f(x)</math> as a trapezoid and calculating its area. This is easily calculated by noting that the area of the region is made up of a rectangle with width <math>(b - a)</math> and height <math>f(a)</math>, and a triangle of width <math>(b-a)</math> and height <math>f(b) - f(a)</math>.

Letting <math>A_{r}</math> denote the area of the rectangle and <math>A_\text{t}</math> the area of the triangle, it follows that <math display="block">

A_\text{r} = (b - a) \cdot f(a), \quad

A_\text{t} = \tfrac{1}{2} (b - a) \cdot [f(b) - f(a)].

</math>

Therefore, <math display="block"> \begin{align}

\int_a^b f(x) \, dx

&\approx A_\text{r} + A_\text{t} \\

&= (b - a) \cdot f(a) + \tfrac{1}{2} (b - a) \cdot [f(b) - f(a)] \\

&= (b - a) \cdot \left(f(a) + \tfrac{1}{2} f(b) - \tfrac{1}{2} f(a)\right) \\

&= (b - a) \cdot \left(\tfrac{1}{2} f(a) + \tfrac{1}{2} f(b)\right) \\

&= (b - a) \cdot \tfrac{1}{2}[f(a) + f(b)].

\end{align} </math>

The rule can also be derived by replacing the integrand with the equation of the line joining points <math>\big(a, f(a)\big)</math> and <math>\big(b, f(b)\big)</math>, which using the two point form of the equation of a line, is <math display="block">

y = (x - a)\,\frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} + f(a).

</math>

Therefore, <math display="block">

\begin{align}

\int_a^b f(x) \, dx

&\approx \int_a^b (x - a)\,\frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} + f(a) \, dx \\

&= \left[\frac{1}{2} (x - a)^2 \,\frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} + xf(a) \right]_{x=a}^{x=b} \\

&= \left[\frac{1}{2} (b - a)^2 \,\frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} + bf(a) \right] - af(a) \\

&= \frac{1}{2} (b - a) [f(b) - f(a)] + (b - a) f(a) \\

&= \frac{1}{2} (b - a) [f(a) + f(b)],

\end{align}

</math> as before.

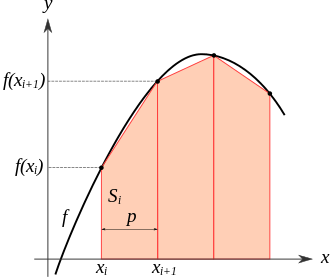

The integral can be even better approximated by partitioning the integration interval, applying the trapezoidal rule to each subinterval and summing the results. In practice, this "chained" (or "composite") trapezoidal rule is usually what is meant by "integrating with the trapezoidal rule". Let <math>\{x_k\}</math> be a partition of <math>[a, b]</math> such that <math>a = x_0 < x_1 < \cdots < x_{N-1} < x_N = b,</math> and <math>\Delta x_k</math> be the length of the <math>k</math>-th subinterval (that is, <math>\Delta x_k = x_k - x_{k-1}</math>), then <math display="block">

\int_a^b f(x) \, dx \approx \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{f(x_{k-1}) + f(x_k)}{2} \Delta x_k.

</math> The trapezoidal rule may be viewed as the result obtained by averaging the left and right Riemann sums and is sometimes defined this way.

The approximation becomes more accurate as the resolution of the partition increases (that is, for larger <math>N</math>, all <math>\Delta x_k</math> decrease).

When the partition has a regular spacing, as is often the case, that is, when all the <math>\Delta x_k</math> have the same value <math>\Delta x,</math> the formula can be simplified for calculation efficiency by factoring <math>\Delta x</math> out: <math display="block">

\int_a^b f(x) \, dx \approx \Delta x \left(\frac{f(x_0) + f(x_N)} 2 + \sum_{k=1}^{N-1} f(x_k) \right).

</math>

As discussed below, it is also possible to place error bounds on the accuracy of the value of a definite integral estimated using a trapezoidal rule.

History

A 2016 Science paper reports that the trapezoid rule was in use in Babylon before 50 BCE for integrating the velocity of Jupiter along the ecliptic.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Numerical implementation

Non-uniform grid

When the grid spacing is non-uniform, one can use the formula <math display="block">

\int_a^b f(x) \,dx \approx \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{f(x_{k-1}) + f(x_k)}{2} \Delta x_k,

</math> where <math>\Delta x_k = x_k - x_{k-1},</math> or more a computationally efficient formula <math display="block">

\int_a^b f(x) \,dx \approx \frac{1}{2} \biggl(f(x_0) \Delta_{+1} x_0 + f(x_N) \Delta_{-1} x_N + \sum_{k=1}^{N-1} f(x_k) \Delta_{\pm1} x_k\biggr),

</math> where <math>\Delta_{+1} x_0 = x_1 - x_0,</math> <math>\Delta_{-1} x_N = x_N - x_{N-1},</math> <math>\Delta_{\pm1} x_k = x_{k+1} - x_{k-1}</math> are the corresponding forward, backward, and central differences.

Uniform grid

For a domain partitioned by <math>N</math> equally spaced points, considerable simplification may occur.

Let <math>\Delta x = \frac{b - a}{N}</math> and <math>x_k = a + k \Delta x</math> for <math>k = 0, 1, \ldots, N.</math> The approximation to the integral becomes <math display="block">\begin{align}

\int_a^b f(x) \,dx

&\approx \frac{\Delta x}{2} \sum_{k=1}^N [f(x_{k-1}) + f(x_{k})] \\

&= \Delta x \biggl( \tfrac12f(x_0) + \tfrac12f(x_N) + \sum_{k=1}^{N-1} f(x_k) \biggr).

\end{align}</math>

Sometimes this expression is written as <math display=block> \Delta x \!\! \mathop{\ \sum\vphantom\big)'}_{k=0}^{N} f(x_k), </math>

where the symbol Template:Tmath indicates that the first and last terms are halved.

Error analysis

The error of the composite trapezoidal rule is the difference between the value of the integral and the numerical result: <math display="block"> \text{E} = \int_a^b f(x)\,dx - \frac{b-a}{N} \left[ {f(a) + f(b) \over 2} + \sum_{k=1}^{N-1} f \left( a+k \frac{b-a}{N} \right) \right]</math>

There exists a number ξ between a and b, such thatTemplate:Sfn <math display="block"> \text{E} = -\frac{(b-a)^3}{12N^2} f(\xi)</math>

It follows that if the integrand is concave up (and thus has a positive second derivative), then the error is negative and the trapezoidal rule overestimates the true value. This can also be seen from the geometric picture: the trapezoids include all of the area under the curve and extend over it. Similarly, a concave-down function yields an underestimate because area is unaccounted for under the curve, but none is counted above. If the interval of the integral being approximated includes an inflection point, the sign of the error is harder to identify.

An asymptotic error estimate for N → ∞ is given by <math display="block"> \text{E} = -\frac{(b-a)^2}{12N^2} \big[ f'(b)-f'(a) \big] + O(N^{-3}). </math> Further terms in this error estimate are given by the Euler–Maclaurin summation formula.

Several techniques can be used to analyze the error, including:Template:Sfn

- Fourier series

- Residue calculus

- Euler–Maclaurin summation formulaTemplate:SfnTemplate:Sfn

- Polynomial interpolationTemplate:Sfn

It is argued that the speed of convergence of the trapezoidal rule reflects and can be used as a definition of classes of smoothness of the functions.Template:Sfn

Proof

First suppose that <math>h=\frac{b-a}{N}</math> and <math>a_k=a+(k-1)h</math>. Let <math display="block"> g_k(t) = \frac{1}{2} t[f(a_k)+f(a_k+t)] - \int_{a_k}^{a_k+t} f(x) \, dx</math> be the function such that <math> |g_k(h)| </math> is the error of the trapezoidal rule on one of the intervals, <math> [a_k, a_k+h] </math>. Then <math display="block"> {dg_k \over dt}={1 \over 2}[f(a_k)+f(a_k+t)]+{1\over2}t\cdot f'(a_k+t)-f(a_k+t),</math> and <math display="block"> {d^2g_k \over dt^2}={1\over 2}t\cdot f(a_k+t).</math>

Now suppose that <math> \left| f(x) \right| \leq \left| f(\xi) \right|, </math> which holds if <math> f </math> is sufficiently smooth. It then follows that <math display="block"> \left| f(a_k+t) \right| \leq f(\xi)</math> which is equivalent to <math> -f(\xi) \leq f(a_k+t) \leq f(\xi)</math>, or <math> -\frac{f(\xi)t}{2} \leq g_k(t) \leq \frac{f(\xi)t}{2}.</math>

Since <math> g_k'(0)=0</math> and <math> g_k(0)=0</math>, <math display="block"> \int_0^t g_k(x) dx = g_k'(t)</math> and <math display="block"> \int_0^t g_k'(x) dx = g_k(t).</math>

Using these results, we find <math display="block"> -\frac{f(\xi)t^2}{4} \leq g_k'(t) \leq \frac{f(\xi)t^2}{4}</math> and <math display="block"> -\frac{f(\xi)t^3}{12} \leq g_k(t) \leq \frac{f(\xi)t^3}{12}</math>

Letting <math> t = h </math> we find <math display="block"> -\frac{f(\xi)h^3}{12} \leq g_k(h) \leq \frac{f(\xi)h^3}{12}.</math>

Summing all of the local error terms we find <math display="block"> \sum_{k=1}^{N} g_k(h) = \frac{b-a}{N} \left[ {f(a) + f(b) \over 2} + \sum_{k=1}^{N-1} f \left( a+k \frac{b-a}{N} \right) \right] - \int_a^b f(x)dx.</math>

But we also have <math display="block"> - \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{f(\xi)h^3}{12} \leq \sum_{k=1}^N g_k(h) \leq \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{f(\xi)h^3}{12}</math> and <math display="block"> \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{f(\xi)h^3}{12}=\frac{f(\xi)h^3N}{12},</math>

so that

<math display="block"> -\frac{f(\xi)h^3N}{12} \leq \frac{b-a}{N} \left[ {f(a) + f(b) \over 2} + \sum_{k=1}^{N-1} f \left( a+k \frac{b-a}{N} \right) \right]-\int_a^bf(x)dx \leq \frac{f(\xi)h^3N}{12}.</math>

Therefore the total error is bounded by

<math display="block"> \text{error} = \int_a^b f(x)\,dx - \frac{b-a}{N} \left[ {f(a) + f(b) \over 2} + \sum_{k=1}^{N-1} f \left( a+k \frac{b-a}{N} \right) \right] = \frac{f(\xi)h^3N}{12}=\frac{f(\xi)(b-a)^3}{12N^2}.</math>

Periodic and peak functions

The trapezoidal rule converges rapidly for periodic functions. This is an easy consequence of the Euler–Maclaurin summation formula, which says that if <math>f</math> is <math>p</math> times continuously differentiable with period <math>T,</math> then <math display="block">

\sum_{k=0}^{N-1} f(kh)h =

\int_0^T f(x)\,dx +

\sum_{k=1}^{\lfloor p/2\rfloor} \frac{B_{2k}}{(2k)!} \left(f^{(2k - 1)}(T) - f^{(2k - 1)}(0)\right) - (-1)^p h^p \int_0^T\tilde{B}_{p}(x/T)f^{(p)}(x) \, dx,

</math> where <math>h := T/N,</math> and <math>\tilde{B}_p</math> is the periodic extension of the <math>p</math>-th Bernoulli polynomial.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Due to the periodicity, the derivatives at the endpoint cancel, and we see that the error is <math>O(h^p)</math>.

A similar effect is available for peak-like functions, such as Gaussian, Exponentially modified Gaussian and other functions with derivatives at integration limits that can be neglected.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The evaluation of the full integral of a Gaussian function by trapezoidal rule with 1% accuracy can be made using just 4 points.<ref name=":0">Template:Cite journal</ref> Simpson's rule requires 1.8 times more points to achieve the same accuracy.<ref name=":0" />Template:Sfn

"Rough" functions

For functions that are not in C2, the error bound given above is not applicable. Still, error bounds for such rough functions can be derived, which typically show a slower convergence with the number of function evaluations <math>N</math> than the <math>O(N^{-2})</math> behaviour given above. Interestingly, in this case the trapezoidal rule often has sharper bounds than Simpson's rule for the same number of function evaluations.Template:Sfn

Applicability and alternatives

The trapezoidal rule is one of a family of formulas for numerical integration called Newton–Cotes formulas, of which the midpoint rule is similar to the trapezoid rule. Simpson's rule is another member of the same family, and in general has faster convergence than the trapezoidal rule for functions which are twice continuously differentiable, though not in all specific cases. However, for various classes of rougher functions (ones with weaker smoothness conditions), the trapezoidal rule has faster convergence in general than Simpson's rule.Template:Sfn

Moreover, the trapezoidal rule tends to become extremely accurate when periodic functions are integrated over their periods, which can be analyzed in various ways. Convergence usually is exponential or faster.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn A similar effect is available for peak functions.<ref name=":0" />Template:Sfn

For non-periodic functions, however, methods with unequally spaced points such as Gaussian quadrature and Clenshaw–Curtis quadrature are generally far more accurate; Clenshaw–Curtis quadrature can be viewed as a change of variables to express arbitrary integrals in terms of periodic integrals, at which point the trapezoidal rule can be applied accurately.

Numerical examples

Approximating the natural logarithm of 3

Since <math display="block">

\int_1^3 \frac{1}{x} \,dx = \ln 3 - \ln 1 = \ln 3,

</math> we can use the trapezoidal rule to approximate the integral, thereby generating an approximation of <math>\ln 3</math>.

Applying the rule with <math>n = 3</math> segments gives <math display="block">

\ln 3 = \int_1^3 \frac{1}{x} \,dx

\approx \frac{1}{3} \left(1 + \frac{6}{5} + \frac{6}{7} + \frac{1}{3}\right)

= \frac{356}{315} \approx 1.13015873,

</math> which has absolute error of <math>0.031546</math> and a relative error of <math>2.87148\%</math>.

Applying the rule with <math>n = 6</math> segments gives <math display="block">

\ln 3 = \int_1^3 \frac{1}{x} \,dx

\approx \frac{1}{6} \left(1 + \frac{3}{2} + \frac{6}{5} + 1 + \frac{6}{7} + \frac{3}{4} + \frac{1}{3}\right)

= \frac{2789}{2520} \approx 1.10674603,

</math> which has absolute error of <math>8.13 \times 10^{-3}</math> and a relative error of <math>0.74036\%</math>.

Approximating the integral of a product

The following integral is given: <math display="block">

\int_{0.1}^{1.3} 5xe^{- 2x} \,dx.

</math> Template:Ordered list Solution Template:Ordered list{\text{true value}} \right| \times 100\% \\

&= \left| \frac{0.05002}{0.89387} \right| \times 100\% \\

&= 5.5959\%.

\end{align}</math> }}

See also

- Gaussian quadrature

- Newton–Cotes formulas

- Rectangle method

- Romberg's method

- Simpson's rule

- Clenshaw–Curtis quadrature

- Tai's model

- Template:Slink

Notes

Template:Notelist <references/>

References

External links

- I. P. Mysovskikh, Trapezium formula, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, ed. M. Hazewinkel

- Notes on the convergence of trapezoidal-rule quadrature

- An implementation of trapezoidal quadrature provided by Boost.Math