Uganda Railway

Template:Short description Template:About Template:Use dmy dates Template:Infobox company Template:History of Kenya The Uganda Railway was a metre-gauge railway system and former British state-owned railway company. The line linked the interiors of Uganda and Kenya with the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa in Kenya. After a series of mergers and splits, the line is now in the hands of the Kenya Railways Corporation and the Uganda Railways Corporation.

Construction

Background

Before the railway's construction, the Imperial British East Africa Company had begun the Mackinnon-Sclater road, a Template:Convert ox-cart track from Mombasa to Busia in Kenya, in 1890.Template:Sfn

In July 1890, Britain was party to a series of anti-slavery measures agreed at the Brussels Conference Act of 1890. In December 1890, a letter from the Foreign Office to the treasury proposed constructing a railway from Mombasa to Uganda to disrupt the traffic of slaves from its source in the interior to the coast.<ref name=Whitehouse>Template:Harvnb</ref>

With steam-powered access to Uganda, the British could transport people and soldiers to ensure dominance of the African Great Lakes region.Template:Sfn

In December 1891 Captain James Macdonald began an extensive survey which lasted until November 1892. At the time there was only one caravan route across the length of the country, forcing Macdonald and his party to march Template:Convert across unknown routes with limited supplies of water or food. The survey led to the first general map of the region.<ref name=Whitehouse2>Template:Harvnb</ref>

The Uganda Railway was named after its ultimate destination, for its entire original Template:Convert length actually lay in what would become Kenya.Template:Sfn Construction began at the port city of Mombasa in British East Africa in 1896 and finished at the line's terminus, Kisumu, on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria, in 1901.Template:Sfn

Engineering

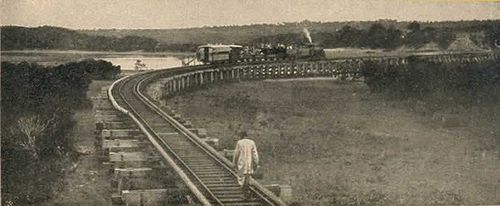

The railway is Template:RailGauge gauge<ref name="treves-57">Template:Cite book</ref> and virtually all single-track with passing loops at stations. 200,000 individual Template:Convert rail-lengths and 1.2 million sleepers, 200,000 fish-plates, 400,000 fish-bolts and 4.8 million steel keys plus steel girders for viaducts and causeways had to be imported from India, necessitating the creation of a modern port at Kilindini Harbour in Mombasa. The railway was a huge logistical achievement and became strategically and economically vital for both Uganda and Kenya. It helped to suppress slavery, by removing the need for humans in the transport of goods.<ref>Template:Cite EB1911</ref>

Management

Template:Infobox UK legislation In August 1895, a bill was introduced at Westminster, becoming the Template:Visible anchor (59 & 60 Vict. c. 38), which authorised the construction of a railway from Mombasa to the shores of Lake Victoria.Template:Sfn The man tasked with building the railway was George Whitehouse, an experienced civil engineer who had worked across the British Empire. Whitehouse acted as the Chief Engineer between 1895 and 1903, also serving as the railway's manager from its opening in 1901. The consulting engineers were Sir Alexander Rendel of Sir A. Rendel & Son and Frederick Ewart Robertson.Template:Sfn

Workers

The construction of the Uganda Railway between Mombasa and Lake Victoria relied heavily on imported labour from British India. Recruitment was overseen from Karachi, with Lahore serving as the main centre for sourcing workers from Punjabi villages.<ref name="ClaytonSavage2">Clayton, Anthony; Savage, Donald C. (1974). Government and Labour in Kenya 1895–1963. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-2886-7.</ref> More than 30,000 labourers were contracted, the majority from Punjab and Gujarat, particularly Sikhs and Gujaratis.<ref name="Aalders20212">Aalders, J.T. (2021). "Building on the Ruins of Empire: The Uganda Railway and the Making of Modern Kenya." Third World Quarterly, 42(8): 1628–1645. doi:10.1080/01436597.2020.1741345. S2CID 225184402.</ref> Officials turned to Indian labour because African recruitment was limited by resistance to colonial mobilisation and by the perception that Indians possessed more experience in railway construction.<ref name="Ruchman20172">Ruchman, S.G. (2017). "Colonial Construction: Labor Practices and Precedents." African Studies Review, 60(2): 97–118. doi:10.1017/asr.2017.53. S2CID 158465963.</ref>

Contracts nominally promised wages of twelve rupees per month, rations, medical care, and return passage.<ref name="ClaytonSavage2" /> In practice, historians emphasise that the working environment was extremely harsh. Aalders notes that the railway was built under "extremely harsh conditions", exposing thousands of Indian workers to disease, famine, and hostile terrain.<ref name="Aalders20212" /> Aselmeyer similarly describes "deplorable living conditions, low wages, and hazardous working conditions", and argues that colonial commemoration of the line as an engineering feat obscured the suffering it entailed.<ref name="Aselmeyer20222">Aselmeyer, Norman (2022). "Ruin of Empire: The Uganda Railway and Memory Work in Kenya." Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, 14(1): 108–128. doi:10.3167/jemms.2022.140102.</ref> Long hours, inadequate rations, overcrowded housing, and exposure to diseases such as malaria and dysentery led to widespread illness and mortality. Accidents such as landslides, explosions, and falls added to the toll, as did attacks from wildlife, most famously the Tsavo lions.<ref name="ClaytonSavage2" /> Historians estimate that several thousand Indian labourers died during the construction period.<ref name="Aselmeyer20222" />

Labour relations were marked by coercion and resistance. Ruchman notes that desertion was common and considered a major threat to progress, prompting administrators to impose repressive measures including surveillance and restrictions on workers' movements.<ref name="Ruchman20172" /> Colonial reports also recorded high rates of desertion, illness, and breakdowns under the pressure of indenture.<ref name="Ruchman20172" />

The railway's employment system entrenched a racial hierarchy that shaped the colonial economy. The Europeans occupied senior management and technical posts, the Indians worked as clerks, artisans, and supervisors, while the Africans were forced to carry out the hardest and least remunerated tasks.<ref name="Ssebaana20252">Ssebaana, Alex (2025). "Railways as Sites of Identity Formation and Creation: The Case of the KUR and EAR&H in the Jinja–Busoga Region." East African Journal of History and Gender, 2(1): 45–66. doi:10.37284/eajhg.2.1.3525.</ref> Scholars argue that these divisions not only structured the construction workforce but also shaped the colonial labour market for decades afterwards, embedding inequalities that outlasted the railway itself.<ref name="Aselmeyer20222" /><ref name="Ssebaana20252" /> The arrival of Indian workers also laid the foundation for a permanent Indian community in East Africa, as many remained after their contracts expired, establishing themselves as traders, artisans, and clerks.<ref name="Aalders20212" />

Law and order

To maintain law and order, the railway instituted a police department. The force was uniformed and drilled and armed with Martini-Henry rifles.<ref name=US10>Template:Harvnb</ref> The force was composed of Indians and two officers were lent by the Indian government to drill and superintend the force. A maximum of 400 constables were recruited, and the force was handed over to the Protectorate government on completion of the railway.<ref name=US10 />

Resistance

At the turn of the 20th century, the railway construction was disturbed by the resistance by Nandi people led by Koitalel Arap Samoei. He was killed in 1905 by Richard Meinertzhagen, ending the Nandi resistance.<ref name="end">Template:Cite news</ref>

Tsavo man-eating lions

Template:Main The incidents for which the building of the railway may be most noted are the killings of a number of construction workers in 1898, during the building of a bridge across the Tsavo River. Hunting mainly at night, a pair of maneless male lions stalked and killed at least 28 Indian and African workers – although some accounts put the number of victims as high as 135.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Lunatic Express

The Uganda Railway faced a great deal of criticism in Parliament, with many parliamentarians decrying it as exorbitantly expensive. Whilst the concept of cost-benefit analysis did not exist in public spending in the Victorian Era, the huge capital sums of the project nevertheless made many sceptical of the value of the investment. This, coupled with the fatalities and wastage of the personnel constructing it through disease, tribal activity, and hostile wildlife led the Uganda Railway to be dubbed a Lunatic Line:

Political resistance to this "gigantic folly", as Henry Labouchère called it,<ref name="Labouchère 30Apr1900">Template:Cite web</ref> surfaced immediately. Such arguments along with the claim that it would be a waste of taxpayers' money were easily dismissed by the Conservatives. Years before, Joseph Chamberlain had proclaimed that, if Britain were to step away from its "manifest destiny", it would by default leave it to other nations to take up the work that it would have been seen as "too weak, too poor, and too cowardly" to have done itself.<ref name="JChamberlain 01Jun1894">Template:Cite web</ref> Its cost has been estimated by one source at £3 million in 1894 money, which is more than £170 million in 2005 money,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and £5.5 million or £650 million in 2016 money by another source.<ref name =Economist1843/>

Because of the wooden trestle bridges, enormous chasms, prohibitive cost, hostile tribes, men infected by the hundreds by diseases, and man-eating lions pulling railway workers out of carriages at night, the name "Lunatic Line" certainly seemed to fit. Winston Churchill, who regarded it "a brilliant conception", said of the project: "The British art of 'muddling through' is here seen in one of its finest expositions. Through everything—through the forests, through the ravines, through troops of marauding lions, through famine, through war, through five years of excoriating Parliamentary debate, muddled and marched the railway."Template:Sfn

The modern term Lunatic Express was coined by Charles Miller in his 1971 The Lunatic Express: An Entertainment in Imperialism. The term The Iron SnakeTemplate:Sfn comes from an old Nandi prophecy by Orkoiyot Kimnyolei: "An iron snake will cross from the lake of salt to the lands of the Great Lake to quench its thirst.."Template:Sfn

Extensions and branches

Disassembled ferries were shipped from Scotland by sea to Mombasa and then by rail to Kisumu where they were reassembled and provided a service to Port Bell and, later, other ports on Lake Victoria (see section below). An Template:Convert rail line between Port Bell and Kampala was the final link in the chain providing efficient transport between the Ugandan capital and the open sea at Mombasa, more than Template:Convert away.

Branch lines were built to Thika in 1913, Lake Magadi in 1915, Kitale in 1926, Naro Moro in 1927 and from Tororo to Soroti in 1929. In 1929 the Uganda Railway became Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours (KURH), which in 1931 completed a branch line to Mount Kenya and extended the main line from Nakuru to Kampala in Uganda. In 1948 KURH became part of the East African Railways Corporation, which added the line from Kampala to Kasese in western Uganda in 1956.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and extended to it to Arua near the border with Zaïre in 1964.

Inland shipping

Lake Victoria

Template:Main Almost from its inception the Uganda Railway developed shipping services on Lake Victoria. In 1898 it launched the 110 ton Template:SS at Kisumu, having assembled the vessel from a "knock down" kit supplied by Bow, McLachlan and Company of Paisley in Scotland. A succession of further Bow, McLachlan & Co. "knock down" kits followed. The 662 ton sister ships Template:SS and Template:SS (1902 and 1903), the 1,134 ton Template:SS (1907) and the 1,300 ton sister ships Template:SS and Template:SS (1914 and 1915) were combined passenger and cargo ferries. The 812 ton SS Nyanza (launched after Clement Hill) was purely a cargo ship. The 228 ton Template:SS launched in 1913 was a tugboat. Two more tugboats from Bow, McLachlan were added in 1925: Template:SS and Template:SS.<ref name=ClydeBuganda>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name=ClydeBuvuma>Template:Cite web</ref>

Lake Kyoga, Lake Albert and the Nile

The company extended its steamer service with a route across Lake Kyoga and down the Victoria Nile to Pakwach at the head of the Albert Nile. Its Lake Victoria ships were unsuitable for river work so it introduced the stern wheel paddle steamers Template:PS (1910)<ref name=Janus>Template:Cite web</ref> and Template:PS (1913)<ref name=Janus/> for the new service. In the 1920s the company added Template:PS (1925)<ref name=Janus/> and the side wheel paddle steamer Template:PS (1927).<ref name=Janus/>

Safari tourism

As the only modern means of transport from the East African coast to the higher plateaus of the interior, a ride on the Uganda Railway became an essential overture to the safari adventures which grew in popularity in the first two decades of the 20th century. As a result, it usually featured prominently in the accounts written by travelers in British East Africa. The rail journey stirred many a romantic passage, like this one from former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who rode the line to start his world-famous safari in 1909: Template:Cquote

Passengers were invited to ride a platform on the front of the locomotive from which they might see the passing game herds more closely. During Roosevelt's journey, he claimed that "on this, except at mealtime, I spent most of the hours of daylight."

Current status

After independence, the railways in Kenya and Uganda fell into disrepair. In summer 2016, a reporter for The Economist magazine took the Lunatic Express from Nairobi to Mombasa. He found the railway to be in poor condition, departing 7 hours late and taking 24 hours for the journey.<ref name =Economist1843>Template:Cite news</ref> The last metre-gauge train between Mombasa and Nairobi made its run on 28 April 2017.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> The line between Nairobi and Kisumu near the Kenya–Uganda border has been closed since 2012.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

From 2014 to 2016, the China Road and Bridge Corporation built the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) parallel to the original Uganda Railway. Passenger service on the SGR was inaugurated on 31 May 2017. The metre-gauge railway is still used to transport passengers between the new SGR Nairobi Terminus and the old metre-gauge train station in Nairobi city centre.

Research has shown that expectations and hopes for the transformations that the Uganda railway would bring about are similar to contemporary visions about the changes that would happen once East Africa became connected to high-speed fibre-optic broadband.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

In popular culture

A documentary on the construction of the line, The Permanent Way, was made in 1961. John Halkin's 1968 novel, Kenya, focuses on the construction of the railway and its defence during the First World War. The construction also serves as the backdrop to the novel Dance of the Jakaranda (Akashic Books, 2017) by Peter Kimani, and appears early in the novel A History of Burning by Janika Oza (2023).

The Tsavo man-eating lions at Tsavo feature in a factual account by Patterson's 1907 autobiographical book The Man-eaters of Tsavo. They are part of the plot of the 1956 film Beyond Mombasa, The Ghost and the Darkness in 1996, and Chander Pahar, a 2013 Bengali movie based on the 1937 novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay.

Several other films have featured the Uganda Railway, including Bwana Devil, made in 1952. In addition, the 1985 film Out of Africa utilizes its railway equipment in several scenes, albeit out of place.

See also

- Kenya Railways Corporation

- MacKinnon-Sclater road

- Rail transport in Kenya

- Transport in Uganda

- Uganda Railways Corporation

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite webTemplate:Dead link

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite news

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Patience-SteamEA

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Ramaer-SteamLocosEAR

- Template:Ramaer-Gari la Moshi

- Template:Robinson-WorldRailAtlas-7

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

External links

- History of the Uganda Railway

- Template:Frac scale replica of EAR 31 class steam locomotive "Uganda" at Stapleford Miniature railway in the UK

- Template:Citation illustrated description of the Uganda railway

Template:EAR locomotives Template:Kenya topics Template:Authority control Template:Coord missing

- Pages with broken file links

- Uganda Railway

- Rail transport in Uganda

- Rail transport in Kenya

- Rail transport in East Africa

- Economic history of Kenya

- Economic history of Uganda

- Uganda Protectorate

- Kenya Colony

- Metre-gauge railways in Uganda

- Metre-gauge railways in Kenya

- 1896 establishments in Kenya

- Railway companies established in 1896