Yaldabaoth

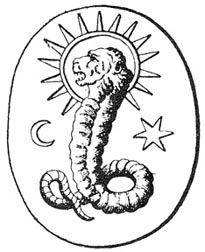

Yaldabaoth, otherwise known as Jaldabaoth or IaldabaothTemplate:Efn (Template:IPAc-en; Template:Langx; Template:Langx;<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Template:Langx Ialtabaôth), is a malevolent god and demiurge (creator of the material world) according to various Gnostic sects, represented sometimes as a theriomorphic, lion-headed serpent.<ref name="Litwa 2016">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="Fischer-Mueller 1990">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Arendzen4">{{#if:||{{#if:Demiurge|![]() |File:PD-icon.svg}} }}{{#if:|One or more of the preceding sentences|This article}} incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: {{#invoke:template wrapper|{{#if:|list|wrap}}|_template=cite Catholic Encyclopedia

|File:PD-icon.svg}} }}{{#if:|One or more of the preceding sentences|This article}} incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: {{#invoke:template wrapper|{{#if:|list|wrap}}|_template=cite Catholic Encyclopedia

|_exclude=inline, noicon, no-icon, prescript, _debug |no-icon=1

}}{{#ifeq: ||

{{#if:Demiurge

|

|{{#if:

|

|{{#if:

|

|}}}}}}}}</ref> He is identified as a false god who keeps souls trapped in physical bodies, imprisoned in the material universe.<ref name="Litwa 2016"/><ref name="Fischer-Mueller 1990"/><ref name="Arendzen4"/>

Etymology

The etymology of the name Yaldabaoth has been subject to many speculative theories. The first etymology was advanced in 1575 by François Feuardent, supposedly translating it from Hebrew to mean Template:Langx.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:R A theory proposed by Jacques Matter in 1828 identified the name as descending from Template:Langx and from Template:Langx, a supposed plural form of Template:Langx. Matter however interpreted it to mean 'chaos', thus translating Yaldaboath as "child of darkness [...] an element of chaos".<ref name="Matter">Template:Cite book</ref>Template:R

This etymology was popular due to its perceived literary merits.Template:Efn It inspired Adolf Hilgenfeld to keep Matter's proposed 'chaos' translation, while fabulating a more plausible sounding, but unattested second noun: Aramaic: בהותא, romanized: bāhūthā, deriving the name from Aramaic: ילדא בהותא, romanized: yaldā bāhūthā supposedly meaning 'child of chaos' in 1884. This and variants of it became the majority opinion from the late 19th to the mid-20th century which was endorsed by Schenke, Böhlig, and Labib.

This analysis was convincingly deconstructed by Jewish historian of religion Gershom Scholem in 1974,<ref name=YaldaReconsid>Template:Cite journal</ref>Template:Rp who showed the unattested Aramaic term to have been fabulated and attested only in a single corrupted text from 1859, with its listed translation having been transposed from the reading of an earlier etymology, whose explanation seemingly equated "darkness" and "chaos" when translating an unattested supposed plural form of Template:Langx.<ref name=YaldaReconsid/><ref name="Black 1983">Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Rp Consequently most scholars retracted their endorsement (for example, Gilles Quispel did so by lamenting humorously that due its literary merits he believes the originator of the name Yaldabaoth had made the same erroneous association between baoth and tohuwabohu as the former majority opinion).<ref>Template:Citation</ref> Additionally, Scholem argued that based on the earliest textual data, which termed Yaldabaoth "the King of Chaos", he was the progenitor of chaos, not its progeny.<ref name="YaldaReconsid" />

Scholem's own theory rendered the name as Yald' Abaoth. Yald' being Aramaic: ילדא, romanized: yaldāTemplate:Efn but translated as 'begetter', not 'child' and Abaoth being a term attested in magic texts, descending from Template:Langx, one of the names of God in Judaism. Thus he rendered Yald' Abaoth as 'begetter of Sabaoth'.<ref name=YaldaReconsid/> Matthew Black objects to this, because Sabaoth is the name of one of Yaldaboth's sons in some Gnostic texts. Instead he suggests the second noun to be Jewish Aramaic: בהתייה, romanized: behūṯā, lit. 'shame'. Which is cognate with Template:Langx, a term used to replace the name Ba'al in the Hebrew Bible. Thus Blacks' proposal renders Aramaic: ילדא בהתייה, romanized: yaldā behūṯā, lit. 'son of shame/Ba'al'.<ref name="Black-1983">Template:Citation</ref>

In his proposed 1967 etymology Alfred Adam already diverged from the then majority opinion and translated Aramaic: ילדא, romanized: yaldā similarly to Scholem, as Template:Langx. He believed the name's second part to derive from Template:Langx. This he interpreted however to describe more broadly 'the power of generation'; thus suggesting the name to mean 'the bringing forth of the power of generation'.<ref>Template:Citation</ref><ref name="Black-1983" />

Robert M. Grant proposed in 1957 that Ialdabaoth was derived from Yahweh Elohe Zebaoth, "Yahweh God of hosts (armies)" (Template:Langx), a name for the God of Israel found with variants in 1 Samuel 1:3, 2 Samuel 7, Amos (3:13, 5:15-16, 27, and elsewhere) 1 Kings, Jeremiah, Zechariah 3:10, and Psalm 89:9.<ref name="GrantNotes">Template:Cite journal</ref> He notes that the change from the "z" (tzadi) to a "d" (daleth) or a "t" (teth) is sometimes seen in Aramaic.<ref name="GrantNotes"/> fr:Simone Pétrement made an argument against Schloem's etymology through analysis of Gnostic mythic texts, and derived it from Iao Sabaoth, which is attested in the Greek Magical Papyri — possibly independently from Grant, although she would not rule out having read Grant's article at some prior point.<ref name="Petrement1990">Template:Cite book</ref>

Historical origins

Template:Multiple image After the Assyrian conquest of Egypt during the 7th century BCE, Seth was considered an evil deity by the Egyptians and not commonly worshipped, in large part due to his role as the god of foreigners.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> From at least 200 BCE onward, a tradition developed in the Graeco-Egyptian Ptolemaic Kingdom which identified Yahweh, the God of the Jews, with the Egyptian god Seth.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Diverging from previous zoologically multiplicitous depictions, Seth's appearance during the Hellenistic period onwards was depicted as resembling a man with a donkey's head.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref> The Greek practice of interpretatio graeca, ascribing the gods of another people's pantheon to corresponding ones in one's own, had been adopted by the Egyptians after their Hellenisation; during the process of which they had identified Seth with Typhon, a snake-monster, which roars like a lion.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

The story of the Exodus, featured in the Hebrew Bible, speaks of the Jews as a nation betrayed and subjugated by the Pharaoh, for whom Yahweh subjects Egyptians to ten plagues — destroying their country, defiling the Nile, and killing all their first-born sons. Jewish migration within the Hellenised Ptolemaic Kingdom to Greek-speaking Egyptian cities such as Alexandria led to the creation of the Septuagint, a translation of the Hebrew Bible into Koine Greek.<ref name="Ross2021">Template:Cite web</ref> Furthermore, the story of the Exodus was adapted by Ezekiel the Tragedian into the Template:Langx, a Greek play performed in Alexandria and seen by Egyptians and Jews. Egyptian receptions of the Exodus story were widely negative, because it insulted their gods and praised their suffering. Thus it inspired Egyptian works retelling the story, but changing its details to mock the Jews and exalt Egypt and its gods.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

In this context some Egyptians discerned similarities between Yahweh's in-narrative actions and attributes and those of Seth (such as being associated with foreigners, deserts, and storms), in addition to a phonetic resemblance between Template:Langx, Yahweh's name as used by hellenised Jews, and Template:Langx, then considered as the animal of Seth.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> From this arose a popular response to the Jewish accusation that Egyptians were merely worshipping beasts, namely that, in truth, the Jews themselves worshipped a beast, a donkey or a donkey-headed man, ie Seth.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Accusations of onolatry against the Jews, spread from the Egyptian milieu, with its understanding of the donkey's Seth-related importance, to the rest of the Graeco-Roman world, which was largely ignorant of this context. In the most famous variations of narratives alleging Jewish onolatry Antiochus IV Epiphanes, a Seleucid king famous for raiding the Jerusalem Temple, supposedly discovered that its Holiest of Holies was not empty, but instead contained a donkey idol, and Tacitus (early second century CE) claimed that the Jews dedicated in their holiest shrine a statue of a wild ass.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Efn After the emergence of Christianity the same charge was also repeated against its devotees. Most famously so in the earliest known depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus, the Alexamenos graffito, where a Christian by the name of Alexamenos is shown worshipping a donkey-headed crucified god.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="Viladesau">Template:Cite book</ref>

According to Litwa, this tradition forms the basis for the development of Gnostic beliefs about Yaldabaoth.Template:Efn<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Role in Gnosticism

Template:Main Template:Further

Gnosticism originated during the late 1st century CE in non-rabbinical Jewish and early Christian sects.<ref name="Magris 2005">Template:Cite encyclopedia</ref> In the formation of Christianity, various sectarian groups, labeled "gnostics" by their opponents, emphasised spiritual knowledge (gnosis) of the divine spark within, over faith (pistis) in the teachings and traditions of the various communities of Christians.<ref name="May 2008">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="Ehrman 2005"/><ref name="Brakke 2010">Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Gnosticism presents a distinction between the highest, unknowable God, and the Demiurge, "creator" of the material universe.<ref name="May 2008"/><ref name="Ehrman 2005"/><ref name="Brakke 2010"/><ref name="Kvam 1999">Template:Cite book</ref> Gnostics considered the most essential part of the process of salvation to be this personal knowledge, in contrast to faith as an outlook in their worldview along with faith in the ecclesiastical authority.<ref name="May 2008"/><ref name="Ehrman 2005"/><ref name="Brakke 2010"/><ref name="Kvam 1999"/>

In Gnosticism, the biblical serpent in the Garden of Eden was praised and thanked for bringing knowledge (gnosis) to Adam and Eve and thereby freeing them from the malevolent Demiurge's control.<ref name="Kvam 1999" /> Gnostic Christian doctrines rely on a dualistic cosmology that implies the eternal conflict between good and evil, and a conception of the serpent as the liberating savior and bestower of knowledge to humankind opposed to the Demiurge or creator god, identified with the Yahweh from the Hebrew Bible.<ref name="Kvam 1999" /><ref name="Ehrman 2005">Template:Cite book</ref> Some Gnostic Christians (such as Marcionites) considered the Hebrew God of the Old Testament as the evil, false god and creator of the material universe, and the Unknown God of the Gospel, the father of Jesus Christ and creator of the spiritual world, as the true, good God.<ref name="Kvam 1999"/><ref name="Ehrman 2005"/> In the Archontic, Sethian, and Ophite systems, Yaldabaoth is regarded as the malevolent Demiurge and false god of the Old Testament who generated the material universe and keeps the souls trapped in physical bodies, imprisoned in the world full of pain and suffering that he created.<ref name="Litwa 2016"/><ref name="Fischer-Mueller 1990"/><ref name="Arendzen4"/>

However, not all Gnostics regarded the creator of the material universe as inherently evil or malevolent.<ref name="EB1911">Template:Cite EB1911</ref><ref name="Logan 2002">Template:Cite book</ref> For instance, Valentinians believed that the Demiurge is merely an ignorant and incompetent creator, trying to fashion the world as well as he can, but lacking the proper power to maintain its goodness.<ref name="EB1911"/><ref name="Logan 2002"/> They were regarded as heretics by the proto-orthodox Early Church Fathers.<ref name="Kvam 1999"/><ref name="Ehrman 2005"/><ref name="Brakke 2010" />

Yaldabaoth is mentioned mainly in the Archontic, Sethian, and Ophite writings of Gnostic literature,<ref name="Arendzen4"/> most of which have been discovered in the Nag Hammadi library.<ref name="Litwa 2016"/><ref name="Fischer-Mueller 1990"/> In the Apocryphon of John, "Yaldabaoth" is the first of three names of the domineering archon, along with Saklas and Samael. In Pistis Sophia he has lost his claim to rulership and, in the depths of Chaos, together with 49 demons, tortures sacrilegious souls in a scorching hot torrent of pitch. Here he is a lion-faced archon, half flame, half darkness. Yaldabaoth appears as a rebellious angel both in the apocryphal Gospel of Judas and the Gnostic work Hypostasis of the Archons. In some of these Gnostic texts, Yaldabaoth is further identified with the Ancient Roman god Saturnus.<ref name="Arendzen4"/>

Cosmogony and creation myths

Yaldabaoth is the son of Sophia, the personification of wisdom according to Gnosticism, with whom he contends. By creatively becoming matter in goodness and simplicity, Sophia created the imperfect Yaldabaoth, who has no knowledge of the other aeons. From his mother he received the powers of light, but he used them for evil. Sophia rules the Ogdoas, the Demiurge rules the Hebdomas. Yaldabaoth created six more archons and other fellows.<ref>{{#if:||{{#if:Gnosticism|![]() |File:PD-icon.svg}} }}{{#if:|One or more of the preceding sentences|This article}} incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: {{#invoke:template wrapper|{{#if:|list|wrap}}|_template=cite Catholic Encyclopedia

|File:PD-icon.svg}} }}{{#if:|One or more of the preceding sentences|This article}} incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: {{#invoke:template wrapper|{{#if:|list|wrap}}|_template=cite Catholic Encyclopedia

|_exclude=inline, noicon, no-icon, prescript, _debug |no-icon=1

}}{{#ifeq: ||

{{#if:Gnosticism

|

|{{#if:

|

|{{#if:

|

|}}}}}}}}</ref> The angels he created rebelled against Yaldabaoth. To keep the angels in subjection, Yaldabaoth generated the material universe.

In the act of creation, however, Yaldabaoth emptied himself of his supreme power. When Yaldabaoth breathed the soul into the first man, Adam, Sophia instilled in him the divine spark of the spirit. After matter, Yaldabaoth produced the serpent spirit (Ophiomorphos), which is the origin of all evil. The light being Sophia caused the fall of man through the serpent. By eating the forbidden fruit, Adam and Eve became wise and rejected Yaldabaoth. Eventually, Yaldabaoth expelled them from the ethereal region, the Paradise, as punishment.

Yaldabaoth continuously attempted to deprive human beings of the gift of the spark of light which he had unwittingly lost to them, or to keep them in bondage. As punishments, he tried to make humanity acknowledge him as God.<ref name="Fischer-Mueller 1990"/> Because of their lack of worship, he caused the Flood upon the human race, from which a feminine power such as Sophia or Pronoia<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> (Providence) rescued Noah.<ref name="Fischer-Mueller 1990"/> Yaldabaoth made a covenant with Abraham, in which he was obligated to serve him along with his descendants. The Biblical prophets were to proclaim Yaldabaoth's glory, but at the same time, through Sophia's influence, they reminded people of their higher origin and prepared for the coming of Christ. At Sophia's instigation, Yaldabaoth arranged for the generation of Jesus through the Virgin Mary. For his proclamation, he used John the Baptist. At the moment of the baptism organized by Yaldabaoth, Sophia took on the body of Jesus and through it taught people that their destiny was the Kingdom of Light (the spiritual world), not the Kingdom of Darkness (the material universe). Only after his baptism did Jesus receive divine power and could perform miracles. But since Jesus destroyed his kingdom instead of promoting it, Yaldabaoth had him crucified. Before his martyrdom, Christ escaped from the bodily shell and returned to the spiritual world.

See also

Template:Portal Template:Div col

- Ancient Canaanite religion

- Ancient Semitic religion

- Atenism

- Baháʼí Faith and the unity of religion

- Chinese dragon

- Dhimmi

- Dystheism

- Ethical monotheism

- Evil God challenge

- False prophet

- God in Abrahamic religions

- Maltheism

- Moralistic therapeutic deism

- Níðhöggr

- Outline of theology

- Prince of Darkness (Manichaeism)

- Problem of evil

- Problem of Hell

- Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia

- Serpents in the Bible

- Theodicy

- Trickster god

- Urmonotheismus (primitive monotheism)

- Violence in the Bible

- Violence in the Quran

Notes

References

<references />

Further reading

External links

- Pages with broken file links

- Articles incorporating text from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia with Wikisource reference

- Articles incorporating text from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia without Wikisource reference

- Articles incorporating text from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia with an unnamed parameter

- Articles incorporating text from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia with no article parameter

- Chaos gods

- Creator gods

- Demons in Gnosticism

- Early Christianity and Gnosticism

- Evil gods

- Gnostic cosmology

- Gnostic deities

- Lion gods

- Names of God in Gnosticism

- Sethianism

- Snake gods

- Trickster gods

- Yahweh