Hydrogen

Template:About Template:Featured article Template:Pp-vandalism Template:Use American English Template:Use dmy dates Template:Infobox hydrogen Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has the symbolTemplate:NbspH and atomic numberTemplate:Nbsp1. It is the lightest and most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all normal matter. Under standard conditions, hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules with the formulaTemplate:NbspTemplate:Chem2, called dihydrogen, or sometimes hydrogen gas, molecular hydrogen, or simply hydrogen. Dihydrogen is colorless, odorless, non-toxic, and highly combustible. Stars, including the Sun, mainly consist of hydrogen in a plasma state, while on Earth, hydrogen is found as the gasTemplate:NbspTemplate:Chem2 (dihydrogen) and in molecules, such as in water and organic compounds. The most common isotope of hydrogen, 1H, consists of one proton, one electron, and no neutrons.

Hydrogen gas was first produced artificially in the 17thTemplate:Nbspcentury by the reaction of acids with metals. Henry Cavendish, inTemplate:Nbsp1766–1781, identified hydrogen gas as a distinct substance and discovered its property of producing water when burned: this is the origin of hydrogen's name, which means Template:Gloss (from Template:Langx, and Template:Langx). Understanding the colors of light absorbed and emitted by hydrogen was a crucial part of the development of quantum mechanics.

Hydrogen, typically nonmetallic except under extreme pressure, readily forms covalent bonds with most nonmetals, contributing to the formation of compounds like water and various organic substances. Its role is crucial in acid–base reactions, which mainly involve proton exchange among soluble molecules. In ionic compounds, hydrogen can take the form of either a negatively-charged anion, where it is known as hydride, or as a positively-charged cation, Template:Chem2, called a proton. Although tightly bonded to water molecules, protons strongly affect the behavior of aqueous solutions, as reflected in the importance of pH. Hydride, on the other hand, is rarely observed because it tends to deprotonate solvents, yieldingTemplate:NbspTemplate:Chem2.

In the early universe, neutral hydrogen atoms formed about 370,000 years after the Big Bang as the universe expanded and plasma had cooled enough for electrons to remain bound to protons. After stars began to form, most of the hydrogen in the intergalactic medium was re-ionized.

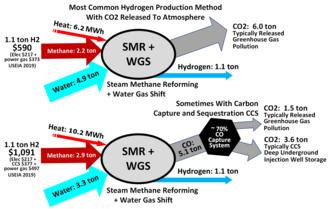

Nearly all hydrogen production is done by transforming fossil fuels, particularly steam reforming of natural gas. It can also be produced from water or saline by electrolysis, but this process is more expensive. Its main industrial uses include fossil fuel processing and ammonia production for fertilizer. Emerging uses for hydrogen include the use of fuel cells to generate electricity.

Properties

Atomic hydrogen

Electron energy levels

Template:Main The ground state energy level of the electron in a hydrogen atom is −13.6Template:NbspelectronvoltsTemplate:Nbsp(eV),<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> equivalent to an ultraviolet photon of roughly 91Template:Nbspnanometers wavelength.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The energy levels of hydrogen are referred to by consecutive quantum numbers, with <math>n=1</math> being the ground state. The hydrogen spectral series corresponds to emission of light due to transitions from higher to lower energy levels.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Rp Each energy level is further split by spin interactions between the electron and proton into four hyperfine levels.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

High-precision values for the hydrogen atom energy levels are required for definitions of physical constants. Quantum calculations have identified nine contributions to the energy levels. The eigenvalue from the Dirac equation is the largest contribution. Other terms include relativistic recoil, the self-energy, and the vacuum polarization terms.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Isotopes

Hydrogen has three naturally-occurring isotopes, denoted Template:Chem, Template:Chem andTemplate:NbspTemplate:Chem. Other, highly-unstable nuclidesTemplate:Nbsp(Template:Chem to Template:Chem) have been synthesized in laboratories but not observed in nature.<ref name="Gurov">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Korsheninnikov">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Template:Chem is the most common hydrogen isotope, with an abundance of >99.98%. Because the nucleus of this isotope consists of only a single proton, it is given the descriptive but rarely used formal name protium.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> It is the only stable isotope with no neutrons (Template:Xref).<ref>Template:NUBASE2020</ref>

Template:Chem, the other stable hydrogen isotope, is known as deuterium and contains one proton and one neutron in the nucleus. Nearly all deuterium nuclei in the universe are thought to have been produced in Big Bang nucleosynthesis, and have endured since then.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>Template:Rp Deuterium is not radioactive, and is not a significant toxicity hazard. Water enriched in molecules that include deuterium instead of normal hydrogen is called heavy water. Deuterium and its compounds are used as a non-radioactive label in chemical experiments and in solvents for Template:Chem-NMR spectroscopy.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Heavy water is used as a neutron moderator and coolant for nuclear reactors. Deuterium is also a potential fuel for commercial nuclear fusion.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Template:Chem is known as tritium and contains one proton and two neutrons in its nucleus. It is radioactive, decaying into helium-3 through beta decay with a half-life of 12.32Template:Nbspyears.<ref name="Miessler" /> It is radioactive enough to be used in luminous paint to enhance the visibility of data displays, such as for painting the hands and dial-markers of watches. The watch glass prevents the small amount of radiation from escaping the case.<ref name="Traub95">Template:Cite web</ref> Small amounts of tritium are produced naturally by cosmic rays striking atmospheric gases; tritium has also been released in nuclear weapons tests.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> It is used in nuclear fusion,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> as a tracer in isotope geochemistry,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> and in specialized self-powered lighting devices.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Tritium has also been used in chemical and biological labeling experiments as a radiolabel.<ref name="holte">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Unique among the elements, distinct names are assigned to hydrogen's isotopes in common use. During the early study of radioactivity, heavy radioisotopes were given their own names, but these are mostly no longer used. The symbols D andTemplate:NbspT (instead of Template:Chem and Template:Chem) are sometimes used for deuterium and tritium, but the symbolTemplate:NbspP was already used for phosphorus and thus was not available for protium.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In its nomenclatural guidelines, the International Union of Pure and Applied ChemistryTemplate:Nbsp(IUPAC) allows any of D, T, Template:Chem, and Template:Chem to be used, though Template:Chem and Template:Chem are preferred.<ref>§ IR-3.3.2, Provisional Recommendations Template:Webarchive, Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry, Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division, IUPAC. Accessed on line 3 October 2007.</ref>

Antihydrogen (Template:Physics particle) is the antimatter counterpart to hydrogen. It consists of an [[antiproton|Template:Shy]] with a positron.<ref name="char15">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="Keller15">Template:Cite journal</ref> The exotic atom muonium (symbol Mu), composed of an antimuon and an electron, is the Template:Shy analogue of hydrogen; Template:AbbrTemplate:Nbspnomenclature incorporates such hypothetical compounds as muonium chlorideTemplate:Nbsp(MuCl) and sodium muonideTemplate:Nbsp(NaMu), analogous to hydrogen chloride and sodium hydride respectively.<ref name="iupac">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Dihydrogen

Under standard conditions, hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules with the formulaTemplate:NbspTemplate:Chem2, officially called "dihydrogen",<ref>Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry IUPAC Recommendations 2005 - Full text (PDF)

2004 version with separate chapters as pdf: IUPAC Provisional Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (2004) Template:Webarchive</ref>Template:Rp but also called "molecular hydrogen",<ref name="britannica">Template:Cite encyclopedia</ref> or simply hydrogen. Dihydrogen is a colorless, odorless, flammable gas.<ref name="britannica"/>

Combustion

File:19. Експлозија на смеса од водород и воздух.webm

Hydrogen gas is highly flammable, reacting with oxygen in air to produce liquid water: Template:Bi The amount of heat released per mole of hydrogen is Template:ValTemplate:Nbsp(kJ), or Template:ValTemplate:Nbsp(MJ) for a Template:Convert mass.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Hydrogen gas forms explosive mixtures with air in concentrations from Template:Val<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> and with chlorine at Template:Val. The hydrogen autoignition temperature, the temperature of spontaneous ignition in air, is Template:Convert.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> In a high-pressure hydrogen leak, the shock wave from the leak itself can heat air to the autoignition temperature, leading to flaming and possibly explosion.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Hydrogen flames emit faint blue and ultraviolet light.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Flame detectors are used to detect hydrogen fires as they are nearly invisible to the naked eye in daylight.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="spinoff-2016" />

Spin isomers

Template:Main Molecular Template:Chem2 exists as two nuclear isomers that differ in the spin states of their nuclei.<ref name="uigi">Template:Cite web</ref> In the Template:Shy form, the spins of the two nuclei are parallel, forming a spin triplet state having a total molecular spin <math>S = 1</math>; in the Template:Shy form the spins are Template:Shy and form a spin singlet state having spin <math>S = 0</math>. The equilibrium ratio of ortho- to para-hydrogen depends on temperature. At room temperature or warmer, equilibrium hydrogen gas contains about 25% of the para form and 75% of the ortho form.<ref name="Green2012">Template:Cite journal</ref> The ortho form is an excited state, having higher energy than the para form by Template:Val,<ref name="PlanckInstitut">Template:Cite web</ref> and it converts to the para form over the course of several minutes when cooled to low temperature.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The thermal properties of these isomers differ because each has distinct rotational quantum states.<ref name="NASA">Template:Cite web</ref>

The ortho-to-para ratio in Template:Chem2 is an important consideration in the liquefaction and storage of liquid hydrogen: the conversion from ortho to para is exothermic, and produces sufficient heat to evaporate most of the liquid if the conversion to Template:Shy does not occur during the cooling process.<ref name="Amos98">Template:Cite web</ref> Catalysts for the ortho-para Template:Shy, such as ferric oxide and activated carbon compounds, are therefore used during hydrogen cooling to avoid this loss of liquid.<ref name="Svadlenak">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Phases

Liquid hydrogen can exist at temperatures below hydrogen's critical point of Template:Convert.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> However, for it to be in a fully liquid state at atmospheric pressure, H2 needs to be cooled to Template:Cvt. Hydrogen was liquefied by James Dewar inTemplate:Nbsp1898 by using regenerative cooling and his invention, the vacuum flask.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Liquid hydrogen becomes solid hydrogen at standard pressure below hydrogen's melting point of Template:Cvt. Distinct solid phases exist, known as PhaseTemplate:NbspI through PhaseTemplate:NbspV, each exhibiting a characteristic molecular arrangement.<ref name="Helled2020">Template:Cite journal</ref> Liquid and solid phases can exist in combination at the triple point; this mixture is known as slush hydrogen.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Metallic hydrogen, a phase obtained at extremely high pressures (in excess of Template:Convert), is an electrical conductor. It is believed to exist deep within giant planets like Jupiter.<ref name="Helled2020"/><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

When ionized, hydrogen becomes a plasma. This is the form in which hydrogen exists within stars.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Thermal and physical properties

| Temperature (K) | Density (kg/m3) | Specific heat (kJ/kg K) | Dynamic viscosity (kg/m s) | Kinematic viscosity (m2/s) | Thermal conductivity (W/m K) | Thermal diffusivity (m2/s) | Prandtl Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 0.24255 | 11.23 | 4.21E-06 | 1.74E-05 | 6.70E-02 | 2.46E-05 | 0.707 |

| 150 | 0.16371 | 12.602 | 5.60E-06 | 3.42E-05 | 0.0981 | 4.75E-05 | 0.718 |

| 200 | 0.1227 | 13.54 | 6.81E-06 | 5.55E-05 | 0.1282 | 7.72E-05 | 0.719 |

| 250 | 0.09819 | 14.059 | 7.92E-06 | 8.06E-05 | 0.1561 | 1.13E-04 | 0.713 |

| 300 | 0.08185 | 14.314 | 8.96E-06 | 1.10E-04 | 0.182 | 1.55E-04 | 0.706 |

| 350 | 0.07016 | 14.436 | 9.95E-06 | 1.42E-04 | 0.206 | 2.03E-04 | 0.697 |

| 400 | 0.06135 | 14.491 | 1.09E-05 | 1.77E-04 | 0.228 | 2.57E-04 | 0.69 |

| 450 | 0.05462 | 14.499 | 1.18E-05 | 2.16E-04 | 0.251 | 3.16E-04 | 0.682 |

| 500 | 0.04918 | 14.507 | 1.26E-05 | 2.57E-04 | 0.272 | 3.82E-04 | 0.675 |

| 550 | 0.04469 | 14.532 | 1.35E-05 | 3.02E-04 | 0.292 | 4.52E-04 | 0.668 |

| 600 | 0.04085 | 14.537 | 1.43E-05 | 3.50E-04 | 0.315 | 5.31E-04 | 0.664 |

| 700 | 0.03492 | 14.574 | 1.59E-05 | 4.55E-04 | 0.351 | 6.90E-04 | 0.659 |

| 800 | 0.0306 | 14.675 | 1.74E-05 | 5.69E-04 | 0.384 | 8.56E-04 | 0.664 |

| 900 | 0.02723 | 14.821 | 1.88E-05 | 6.90E-04 | 0.412 | 1.02E-03 | 0.676 |

| 1000 | 0.02424 | 14.99 | 2.01E-05 | 8.30E-04 | 0.448 | 1.23E-03 | 0.673 |

| 1100 | 0.02204 | 15.17 | 2.13E-05 | 9.66E-04 | 0.488 | 1.46E-03 | 0.662 |

| 1200 | 0.0202 | 15.37 | 2.26E-05 | 1.12E-03 | 0.528 | 1.70E-03 | 0.659 |

| 1300 | 0.01865 | 15.59 | 2.39E-05 | 1.28E-03 | 0.568 | 1.96E-03 | 0.655 |

| 1400 | 0.01732 | 15.81 | 2.51E-05 | 1.45E-03 | 0.61 | 2.23E-03 | 0.65 |

| 1500 | 0.01616 | 16.02 | 2.63E-05 | 1.63E-03 | 0.655 | 2.53E-03 | 0.643 |

| 1600 | 0.0152 | 16.28 | 2.74E-05 | 1.80E-03 | 0.697 | 2.82E-03 | 0.639 |

| 1700 | 0.0143 | 16.58 | 2.85E-05 | 1.99E-03 | 0.742 | 3.13E-03 | 0.637 |

| 1800 | 0.0135 | 16.96 | 2.96E-05 | 2.19E-03 | 0.786 | 3.44E-03 | 0.639 |

| 1900 | 0.0128 | 17.49 | 3.07E-05 | 2.40E-03 | 0.835 | 3.73E-03 | 0.643 |

| 2000 | 0.0121 | 18.25 | 3.18E-05 | 2.63E-03 | 0.878 | 3.98E-03 | 0.661 |

History

18th century

In 1671, Irish scientist Robert Boyle discovered and described the reaction between iron filings and dilute acids, which results in the production of hydrogen gas.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Boyle did not note that the gas was flammable, but hydrogen would play a key role in overturning the phlogiston theory of combustion.<ref name=Ramsay-1896>Template:Cite book</ref>

In 1766, Henry Cavendish was the first to recognize hydrogen gas as a discrete substance, by naming the gas from a metal-acid reaction "inflammable air". He speculated that "inflammable air" was in fact identical to the hypothetical substance "phlogiston"<ref>Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="cav766">Template:Cite journal</ref> and further finding inTemplate:Nbsp1781 that the gas produces water when burned. He is usually given credit for the discovery of hydrogen as an element.<ref name="Nostrand">Template:Cite encyclopedia</ref><ref name="nbb">Template:Cite book</ref>

In 1783, Template:Langr identified the element that came to be known as hydrogen<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> when he and [[Pierre-Simon Laplace|Template:Langr]] reproduced Cavendish's finding that water is produced when hydrogen is burned.<ref name="nbb" /> Template:Langr produced hydrogen for his experiments on mass conservation by treating metallic iron with a stream of water through an incandescent iron tube heated in a fire. Anaerobic oxidation of iron by the protons of water at high temperature can be schematically represented by the set of following reactions:

Many metals react similarly with water, leading to the production of hydrogen.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> In some situations, this H2-producing process is problematic, for instance in the case of zirconium cladding on nuclear fuel rods.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

19th century

By 1806 hydrogen was used to fill balloons.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Template:Langr built the first [[de Rivaz engine|Template:Langr engine]], an internal combustion engine powered by a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen, inTemplate:Nbsp1806. Edward Daniel Clarke invented the hydrogen gas blowpipe inTemplate:Nbsp1819. The [[Döbereiner's lamp|Template:Langr's lamp]] and limelight were invented inTemplate:Nbsp1823. Hydrogen was liquefied for the first time by James Dewar inTemplate:Nbsp1898 by using regenerative cooling and his invention, the vacuum flask. He produced solid hydrogen the next year.<ref name="nbb" />

One of the first quantum effects to be explicitly noticed, although not understood at the time, was James Clerk Maxwell's observation that the specific heat capacity of Template:Chem2 unaccountably departs from that of a diatomic gas below room temperature, and begins to increasingly resemble that of a monatomic gas at cryogenic temperatures. According to quantum theory, this behavior arises from the spacing of the (quantized) rotational energy levels, which are particularly wide-spaced in Template:Chem2 because of its low mass. These widely-spaced levels inhibit equal partition of heat energy into rotational motion in hydrogen at low temperatures. Diatomic gases composed of heavier atoms do not have such widely spaced levels and do not exhibit the same effect.<ref name="Berman">Template:Cite journal</ref>

20th century

The existence of the hydride anion was suggested by [[Gilbert N. Lewis|GilbertTemplate:NbspN. Lewis]] inTemplate:Nbsp1916 for [[Group 1 elements|groupTemplate:Nbsp1]] and [[Group 2 elements|groupTemplate:Nbsp2]] salt-like compounds. InTemplate:Nbsp1920, Template:Langr electrolyzed molten lithium hydrideTemplate:Nbsp(LiH), producing a stoichiometric quantity of hydrogen at the anode.<ref name="Moers">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Because of its simple atomic structure, consisting only of a proton and an electron, the hydrogen atom, together with the spectrum of light produced from it or absorbed by it, has been central to the development of the theory of atomic structure.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> The energy levels of hydrogen can be calculated fairly accurately using the [[Bohr model|Template:Langr model]] of the atom, in which the electron "orbits" the proton, like how Earth orbits the Sun. However, the electron and proton are held together by electrostatic attraction, while planets and celestial objects are held by gravity. Due to the discretization of angular momentum postulated in early quantum mechanics by Template:Langr, the electron in the Template:Langr model can only occupy certain allowed distances from the proton, and therefore only certain allowed energies.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Hydrogen's unique position as the only neutral atom for which the [[Schrödinger equation|Template:Langr equation]] can be directly solved, has significantly contributed to the understanding of quantum mechanics through the exploration of its energetics.<ref name="Laursen04">Template:Cite web</ref> Furthermore, study of the corresponding simplicity of the hydrogen molecule and the corresponding cation, [[H2+|Template:Chem2]], brought understanding of the nature of the chemical bond, which followed shortly after the quantum mechanical treatment of the hydrogen atom had been developed in the mid-1920s.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Hydrogen-lifted airship

[[File:Hindenburg over New York 1937 (cropped).jpg|alt=Airship Hindenburg over New York|thumb|The [[Hindenburg-class airship|Template:Lang]] over New York City inTemplate:Nbsp1937]] Because Template:Chem2 has only 7% the density of air, it was once widely used as a lifting gas in balloons and airships.<ref name="Almqvist03">Template:Cite book</ref> The first hydrogen-filled balloon was invented by Template:Langr inTemplate:Nbsp1783. Hydrogen provided the lift for the first reliable form of air-travel following theTemplate:Nbsp1852 invention of the first hydrogen-lifted airship by Template:Langr. German count [[Ferdinand von Zeppelin|Template:Langr]] promoted the idea of rigid airships lifted by hydrogen that later were called Template:Langr, the first of which had its maiden flight inTemplate:Nbsp1900.<ref name="nbb" /> Regularly-scheduled flights started inTemplate:Nbsp1910 and by the outbreak of World WarTemplate:NbspI in AugustTemplate:Nbsp1914, they had carried 35,000 passengers without a serious incident. Hydrogen-lifted airships in the form of blimps were used as observation platforms and bombers during World WarTemplate:NbspII, especially on the [[US Eastern seaboard|USTemplate:NbspEastern seaboard]].<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

The first non-stop transatlantic crossing was made by the British airshipTemplate:NbspR34 inTemplate:Nbsp1919 and regular passenger service resumed in theTemplate:Nbsp1920s. Hydrogen was used in the [[LZ 129 Hindenburg|Template:Lang]], which caught fire over New Jersey on 6Template:NbspMay 1937.<ref name="nbb" /> The hydrogen that filled the airship was ignited, possibly by static electricity, and burst into flames.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Following this disaster, commercial hydrogen airship travel ceased. Hydrogen is still used, in preference to non-flammable but more expensive helium, as a lifting gas for weather balloons.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Deuterium and tritium

Deuterium was discovered in DecemberTemplate:Nbsp1931 by Harold Urey, and tritium was prepared inTemplate:Nbsp1934 by Ernest Rutherford, Mark Oliphant, and Paul Harteck.<ref name="Nostrand" /> Heavy water, which consists of deuterium in the place of regular hydrogen, was discovered by Urey's group inTemplate:Nbsp1932.<ref name="nbb" />

Chemistry

Reactions of H2

Template:Chem2 is relatively unreactive. The thermodynamic basis of this low reactivity is the very strong Template:Nowr, with a bond dissociation energy of Template:Val.<ref>Template:RubberBible87th</ref> It does form coordination complexes called dihydrogen complexes. These species provide insights into the early steps in the interactions of hydrogen with metal catalysts. According to neutron diffraction, the metal and two HTemplate:Nbspatoms form a triangle in these complexes. The Template:Nowr remains intact but is elongated. They are acidic.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Although exotic on Earth, the Template:Chem2Template:Nbspion is common in the universe. It is a triangular species, like the aforementioned dihydrogen complexes. It is known as protonated molecular hydrogen or the trihydrogen cation.<ref name="Carrington">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Hydrogen reacts with chlorine to produceTemplate:NbspHCl, and with bromine to produceTemplate:NbspHBr, via a chain reaction. The reaction requires initiation. For example, in the case of Br2, the dibromine molecule is split apart: Template:Chem2. Propagating reactions consume hydrogen molecules and produceTemplate:NbspHBr, as well as BrTemplate:Nbspand HTemplate:Nbspatoms: Template:Bi Template:Bi Finally the terminating reaction: Template:Bi Template:Bi consumes the remaining atoms.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Rp

The addition of H2 to unsaturated organic compounds, such as alkenes and alkynes, is called hydrogenation. Even if the reaction is energetically favorable, it does not occur spontaneously even at higher temperatures. In the presence of a catalyst like finely divided platinum or nickel, the reaction proceeds at room temperature.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Rp

Hydrogen-containing compounds

Template:Main Hydrogen can exist in both +1 and −1Template:Nbspoxidation states, forming compounds through ionic and covalent bonding. The element is part of a wide range of substances, including water, hydrocarbons, and numerous other organic compounds.<ref name="hydrocarbon">Template:Cite web</ref> The H+Template:Nbspion—commonly referred to as a proton due to its single proton and absence of electrons—is central to acid–base chemistry, although the proton does not move freely. In the [[Brønsted–Lowry acids|Template:Langr–Lowry]] framework, acids are defined by their ability to donate H+Template:Nbspions to bases.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Hydrogen forms a vast variety of compounds with carbon, known as hydrocarbons, and an even greater diversity with other elements (heteroatoms), giving rise to the broad class of organic compounds often associated with living organisms.<ref name="hydrocarbon"/>

Hydrogen compounds with hydrogen in the oxidation stateTemplate:Nbsp−1 are known as hydrides, which are usually formed between hydrogen and metals. The hydrides can be ionic (aka saline), covalent, or metallic. With heating, H2 reacts efficiently with the alkali and alkaline earth metals to give the ionic hydrides of the formulasTemplate:NbspMH and MH2, respectively. These salt-like crystalline compounds have high melting points and all react with water to liberate hydrogen. Covalent hydrides include boranes and polymeric aluminium hydride. Transition metals form metal hydrides via continuous dissolution of hydrogen into the metal.<ref name=UllmannH2/> A well-known hydride is lithium aluminium hydride: the Template:Chem2Template:Nbspanion carries hydridic centers firmly attached to the Al(III).<ref>Template:Greenwood&Earnshaw2nd</ref> Perhaps the most extensive series of hydrides are the boranes, compounds consisting only of boron and hydrogen.<ref name="Downs">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Hydrides can bond to these electropositive elements not only as a terminal ligand but also as bridging ligands. In diboraneTemplate:Nbsp(Template:Chem2), four hydrogen atoms are terminal, while two bridge between the two boron atoms.<ref name="Miessler" />

Hydrogen bonding

Template:Main When bonded to a more electronegative element, particularly fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen, hydrogen can participate in a form of medium-strength noncovalent bonding with another electronegative element with a lone pair like oxygen or nitrogen. This phenomenon, called hydrogen bonding, is critical to the stability of many biological molecules.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>Template:Rp<ref>IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology, Electronic version, Hydrogen Bond Template:Webarchive</ref> Hydrogen bonding alters molecule structures, viscosity, solubility, melting and boiling points, and even protein folding dynamics.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Protons and acids

In water, hydrogen bonding plays an important role in reaction thermodynamics. A hydrogen bond can shift over to proton transfer. Under the [[Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory|Template:Langr–Lowry acid–base theory]], acids are proton donors, while bases are proton acceptors.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>Template:Rp A bare protonTemplate:Nbsp(Template:Chem2) essentially cannot exist in anything other than a vacuum. Otherwise it attaches to other atoms, ions, or molecules. Even chemical species as inert as methane can be protonated. The term "proton" is used loosely and metaphorically to refer to solvated hydrogen cations attached to other solvated chemical species; it is denotedTemplate:Nbsp"Template:Chem2" without any implication that any single protons exist freely in solution as a species. To avoid the implication of the naked proton in solution, acidic aqueous solutions are sometimes considered to contain the "hydronium ion"Template:Nbsp(Template:Chem2), or still more accurately, Template:Chem2.<ref name="Okumura">Template:Cite journal</ref> Other oxonium ions are found when water is in acidic solution with other solvents.<ref name="Perdoncin">Template:Cite journal</ref>

The concentration of these solvated protons determines the pH of a solution, a logarithmic scale that reflects its acidity or basicity. Lower pHTemplate:Nbspvalues indicate higher concentrations of hydronium ions, corresponding to more acidic conditions.<ref name="housecroft" />

Occurrence

Cosmic

Hydrogen, as atomic H, is the most abundant chemical element in the universe, making up 75% of normal matter by mass.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and >90% by number of atoms.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> In the early universe, protons formed in the first second after the Big Bang; neutral hydrogen atoms formed about 370,000Template:Nbspyears later during the recombination epoch as the universe expanded and plasma had cooled enough for electrons to remain bound to protons.<ref>Template:Cite journal (Revised September 2017) by Keith A. Olive and John A. Peacock.</ref>

In astrophysics, neutral hydrogen in the interstellar medium is called HTemplate:NbspI and ionized hydrogen is called HTemplate:NbspII.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Radiation from stars ionizes HTemplate:NbspI to HTemplate:NbspII, creating [[Strömgren sphere|spheres of ionized HTemplate:NbspII]] around stars. In the chronology of the universe neutral hydrogen dominated until the birth of stars during the era of reionization, which then produced bubbles of ionized hydrogen that grew and merged over hundreds of millions of years.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> These are the source of the 21-centimeter hydrogen line, at Template:Val, that is detected in order to probe primordial hydrogen. The large amount of neutral hydrogen found in the damped Lyman-alpha systems is thought to dominate the cosmological baryonic density of the universe up to a redshift of Template:Nowr.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Hydrogen is found in great abundance in stars and gas giant planets. Molecular clouds of Template:Chem2 are associated with star formation. Hydrogen plays a vital role in powering stars through the proton-proton reaction in lower-mass stars, and through the [[CNO cycle|CNOTemplate:Nbspcycle]] of nuclear fusion in stars more massive than the Sun.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Protonated molecular hydrogenTemplate:Nbsp(Template:Chem2) is found in the interstellar medium, where it is generated by ionization of molecular hydrogen by cosmic rays. This ion has also been observed in the upper atmosphere of Jupiter. The ion is long-lived in outer space due to the low temperature and density. Template:Chem2 is one of the most abundant ions in the universe, and it plays a notable role in the chemistry of the interstellar medium.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Neutral triatomic hydrogen Template:Chem2 can exist only in an excited form and is unstable.<ref name="couple">Template:Citation</ref>

Terrestrial

Hydrogen is the third most abundant element on the Earth's surface,<ref name="ArgonneBasic">Template:Cite journal</ref> mostly existing within chemical compounds such as hydrocarbons and water.<ref name="Miessler">Template:Cite book</ref> Elemental hydrogen is normally in the form of a gas, Template:Chem2, at standard conditions. It is present in a very low concentration in Earth's atmosphere (around Template:Val on a molar basis<ref name="Grinter">Template:Cite journal</ref>) because of its light weight, which enables it to escape the atmosphere more rapidly than heavier gases. Despite its low concentration in the atmosphere, terrestrial hydrogen is sufficiently abundant to support the metabolism of several varieties of bacteria.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Large underground deposits of hydrogen gas have been discovered in several countries including Mali, France and Australia.<ref name="Pearce-2024">Template:Cite web</ref> As of 2024, it is uncertain how much underground hydrogen can be extracted economically.<ref name="Pearce-2024" />

Production and storage

Industrial routes

Nearly all of the world's current supply of hydrogen gasTemplate:Nbsp(Template:Chem2) is produced from fossil fuels.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name="rosenow-2022">Template:Cite journal Article in press.</ref>Template:Rp Many methods exist for producing H2, but three dominate commercially: steam reforming often coupled to water-gas shift, partial oxidation of hydrocarbons, and water electrolysis.<ref name=KO/>

Steam reforming

Hydrogen is mainly produced by steam methane reformingTemplate:Nbsp(SMR), the reaction of water and methane.<ref name="rotech">Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="Oxtoby">Template:Cite book</ref> Thus, at high temperature (Template:Cvt), steam (water vapor) reacts with methane to yield carbon monoxide andTemplate:NbspTemplate:Chem2. Template:Bi Producing one tonne of hydrogen through this process emits Template:ValTemplate:Nbsptonnes of carbon dioxide.<ref name="Bonheure-2021">Template:Cite web</ref> The production of natural gas feedstock also produces emissions such as vented and fugitive methane, which further contributes to the overall carbon footprint of hydrogen.<ref name="Griffiths-20212">Template:Cite journal</ref>

This reaction is favored at low pressures but is nonetheless conducted at high pressuresTemplate:Nbsp(Template:Cvt) because high-pressureTemplate:NbspTemplate:Chem2 is the most marketable product, and pressure swing adsorptionTemplate:Nbsp(PSA) purification systems work better at higher pressures. The product mixture is known as "synthesis gas" because it is often used directly for the production of methanol and many other compounds. Hydrocarbons other than methane can be used to produce synthesis gas with varying product ratios. One of the many complications to this highly-optimized technology is the formation of coke or carbon: Template:Bi

Therefore, steam reforming typically employs an excess ofTemplate:NbspTemplate:Chem2. Additional hydrogen can be recovered from the steam by using carbon monoxide through the water gas shift reactionTemplate:Nbsp(WGS). This process requires an iron oxide catalyst:<ref name="Oxtoby" /> Template:Bi

Hydrogen is sometimes produced and consumed in the same industrial process, without being separated. In the [[Haber process|Template:Langr process]] for ammonia production, hydrogen is generated from natural gas.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Partial oxidation of hydrocarbons

Other methods for CO and Template:Chem2 production include partial oxidation of hydrocarbons:<ref name="uigi"/>

Although less important commercially, coal can serve as a prelude to the above shift reaction:<ref name="Oxtoby" />

Olefin production units may produce substantial quantities of byproduct hydrogen, particularly from cracking light feedstocks like ethane or propane.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Water electrolysis

Electrolysis of water is a conceptually simple method of producing hydrogen. Template:Bi Commercial electrolyzers use nickel-based catalysts in strongly alkaline solution. Platinum is a better catalyst but is expensive.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The hydrogen created through electrolysis using renewable energy is commonly referred to as "green hydrogen".<ref name="RoyalSociety-2021">Template:Cite web</ref>

Electrolysis of brine to yield chlorine<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> also produces high-purity hydrogen as a co-product, which is used for a variety of transformations such as hydrogenations.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

The electrolysis process is more expensive than producing hydrogen from methane without carbon capture and storage.<ref name="Evans-2020">Template:Cite web</ref>

Innovation in hydrogen electrolyzers could make large-scale production of hydrogen from electricity more cost-competitive.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Methane pyrolysis

Hydrogen can be produced by pyrolysis of natural gas (methane), producing hydrogen gas and solid carbon with the aid of a catalyst and Template:Val input heat: Template:Bi The carbon may be sold as a manufacturing feedstock or fuel, or landfilled. This route could have a lower carbon footprint than existing hydrogen production processes, but mechanisms for removing the carbon and preventing it from reacting with the catalyst remain obstacles for industrial-scale use.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>Template:Rp<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Thermochemical

Water splitting is the process by which water is decomposed into its components. Relevant to the biological scenario is this equation: Template:Bi The reaction occurs in the light-dependent reactions in all photosynthetic organisms. A few organisms, including the alga Template:Lang and cyanobacteria, have evolved a second step in the dark reactions in which protons and electrons are reduced to form Template:Chem2Template:Nbspgas by specialized hydrogenases in the chloroplast.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Efforts have been undertaken to genetically modify cyanobacterial hydrogenases to more efficiently generate Template:Chem2Template:Nbspgas even in the presence of oxygen.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Efforts have also been undertaken with genetically‐modified alga in a bioreactor.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Relevant to the thermal water-splitting scenario is this simple equation: Template:Bi Over 200 thermochemical cycles can be used for water splitting. Many of these cycles such as the iron oxide cycle, cerium(IV) oxide–cerium(III) oxide cycle, zinc–zinc oxide cycle, sulfur–iodine cycle, copper–chlorine cycle and hybrid sulfur cycle have been evaluated for their commercial potential to produce hydrogen and oxygen from water and heat without using electricity.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> A number of labs (including in France, Germany, Greece, Japan, and the United States) are developing thermochemical methods to produce hydrogen from solar energy and water.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Natural routes

Biohydrogen

Template:Further Template:Chem2 is produced in organisms by enzymes called hydrogenases. This process allows the host organism to use fermentation as a source of energy.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> These same enzymes also can oxidizeTemplate:NbspH2, such that the host organisms can subsist by reducing oxidized substrates using electrons extracted fromTemplate:NbspH2.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Hydrogenase enzymes feature iron or iron–nickel centers at their active sites.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> The natural cycle of hydrogen production and consumption by organisms is called the hydrogen cycle.<ref name="Rhee6">Template:Cite journal</ref>

Some bacteria such as Template:Lang can use the small amount of hydrogen in the atmosphere as a source of energy when other sources are lacking. Their hydrogenases feature small channels that exclude oxygen from the active site, permitting the reaction to occur even though the hydrogen concentration is very low and the oxygen concentration is as in normal air.<ref name=Grinter/><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Confirming the existence of hydrogenase‐employing microbes in the human gut, Template:Chem2 occurs in human breath. The concentration in the breath of fasting people at rest is typically under Template:ValTemplate:Nbsp(ppm), but can reach Template:Val when people with intestinal disorders consume molecules they cannot absorb during diagnostic hydrogen breath tests.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Serpentinization

Serpentinization is a geological mechanism which produces highly-reducing conditions.<ref name=FrostBeard2007>Template:Cite journal</ref> Under these conditions, water is capable of oxidizing ferrousTemplate:Nbsp(Template:Chem) ions in fayalite, generating hydrogen gas:<ref name="Dincer-2015">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Template:Bi

Closely related to this geological process is the [[Schikorr reaction|Template:Langr reaction]]: Template:Bi This process also is relevant to the corrosion of iron and steel in oxygen-free groundwater and in reducing soils below the water table.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Laboratory syntheses

Template:Chem2 is produced in laboratory settings, such as in the small-scale electrolysis of water using metal electrodes and water containing an electrolyte, which liberates hydrogen gas at the cathode:<ref name="housecroft" /> Template:Bi Hydrogen is also often a by-product of other reactions. Many metals react with water to produceTemplate:NbspTemplate:Chem2, but the rate of hydrogen evolution depends on the metal, the pH, and the presence of alloying agents. Most often, hydrogen evolution is induced by acids. The alkali and alkaline earth metals as well as aluminium, zinc, manganese, and iron, react readily with aqueous acids.<ref name="housecroft">Template:Cite book</ref> Template:Bi

Many metals, such as aluminium, are slow to react with water because they form passivated oxide coatings. An alloy of aluminium and gallium, however, does react with water. In high-pH solutions, aluminium can react with Template:NbspTemplate:Chem2:<ref name="housecroft" />

Storage

If H2 is to be used as an energy source, its storage is important. It dissolves only poorly in solvents. For example, at room temperature and Template:Convert, Template:ApproxTemplate:NbspTemplate:Val of hydrogen dissolve into Template:Convert of diethyl ether.<ref name="UllmannH2">Template:Cite book</ref> H2 can be stored in compressed form, although compressing costs energy. Liquefaction is impractical given hydrogen's low critical temperature. In contrast, ammonia and many hydrocarbons can be liquified at room temperature under pressure. For these reasons, hydrogen carriers—materials that reversibly bindTemplate:NbspH2—have attracted much attention. The key question is then the weight percent of H2-equivalents within the carrier material. For example, hydrogen can be reversibly absorbed into many rare earths and transition metals<ref name="Takeshita">Template:Cite journal</ref> and is soluble in both nanocrystalline and amorphous metals.<ref name="Kirchheim1">Template:Cite journal</ref> Hydrogen solubility in metals is influenced by local distortions or impurities in the crystal lattice.<ref name="Kirchheim2">Template:Cite journal</ref> These properties may be useful when hydrogen is purified by passage through hot palladium disks, but the gas's high solubility is also a metallurgical problem, contributing to the embrittlement of many metals,<ref name="Rogers 1999 1057–1064">Template:Cite journal</ref> complicating the design of pipelines and storage tanks.<ref name="Christensen">Template:Cite news</ref>

The most problematic aspect of metal hydrides for storage is their modest H2Template:Nbspcontent, often on the order ofTemplate:Nbsp1%. For this reason, there is interest in storage of H2 in compounds of low molecular weight. For example, ammonia borane (Template:Chem2) contains 19.8Template:Nbspweight percent ofTemplate:NbspH2. The problem with this material is that after release of H2, the resulting boron nitride does not re-add H2: i.e., ammonia borane is an irreversible hydrogen carrier.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> More attractive are hydrocarbons such as tetrahydroquinoline, which reversibly release someTemplate:NbspH2 when heated in the presence of a catalyst:<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Template:Bi

Applications

Petrochemical industry

Large quantities of Template:Chem2 are used in the "upgrading" of fossil fuels. Key consumers of Template:Chem2 include hydrodesulfurization and hydrocracking. Many of these reactions can be classified as hydrogenolysis, i.e., the cleavage of bonds by hydrogen. Illustrative is the separation of sulfur from liquid fossil fuels:<ref name=KO>Template:Cite book</ref><ref name="UllmannHuse">Template:Cite book</ref> Template:Bi

Hydrogenation

Hydrogenation, the addition of Template:Chem2 to various substrates, is done on a large scale. Hydrogenation of Template:Chem2 produces ammonia by the [[Haber process|Template:Langr process]]:<ref name="UllmannHuse" /> Template:Bi This process consumes a few percent of the energy budget in the entire industry and is the biggest consumer of hydrogen. The resulting ammonia is used extensively in fertilizer production; these fertilizers have become essential feedstocks in modern agriculture.<ref name="Smil_2004_Enriching">Template:Cite book</ref> Hydrogenation is also used to convert unsaturated fats and oils to saturated fats and oils. The major application is the production of margarine. Methanol is produced by hydrogenation of carbon dioxide; the mixture of hydrogen and carbon dioxide used for this process is known as syngas. It is similarly the source of hydrogen in the manufacture of hydrochloric acid. Template:Chem2 is also used as a reducing agent for the conversion of some ores to the metals.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="housecroft" />

Fuel

The potential for using hydrogenTemplate:Nbsp(H2) as a fuel has been widely discussed. Hydrogen can be used in fuel cells to produce electricity,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> or burned to generate heat.<ref name="Lewis-2021">Template:Cite journalTemplate:Creative Commons text attribution notice</ref> When hydrogen is consumed in fuel cells, the only emission at the point of use is water vapor.<ref name="Lewis-2021" /> When burned, hydrogen produces relatively little pollution at the point of combustion, but can lead to thermal formation of harmful nitrogen oxides.<ref name="Lewis-2021" />

If hydrogen is produced with low or zero greenhouse gas emissions (green hydrogen), it can play a significant role in decarbonizing energy systems where there are challenges and limitations to replacing fossil fuels with direct use of electricity.<ref name="IPCC-2022" /><ref name="Evans-2020" />

Hydrogen fuel can produce the intense heat required for industrial production of steel, cement, glass, and chemicals, thus contributing to the decarbonization of industry alongside other technologies, such as electric arc furnaces for steelmaking.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> However, it is likely to play a larger role in providing industrial feedstock for cleaner production of ammonia and organic chemicals.<ref name="IPCC-2022">Template:Cite book</ref> For example, in steelmaking, hydrogen could function as a clean fuel and also as a low-carbon catalyst, replacing coal-derived coke (carbon):<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Template:Bi Template:Bi Template:Bi Hydrogen used to decarbonize transportation is likely to find its largest applications in shipping, aviation and, to a lesser extent, heavy goods vehicles, through the use of hydrogen-derived synthetic fuels such as ammonia and methanol and fuel cell technology.<ref name="IPCC-2022" /> For light-duty vehicles including cars, hydrogen is far behind other alternative fuel vehicles, especially compared with the rate of adoption of battery electric vehicles, and may not play a significant role in future.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen together serve as cryogenic propellants in liquid-propellant rockets, as in the Space Shuttle main engines. NASA has investigated the use of rocket propellant made from atomic hydrogen, boron or carbon that is frozen into solid molecular hydrogen particles suspended in liquid helium. Upon warming, the mixture vaporizes to allow the atomic species to recombine, heating the mixture to high temperature.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Hydrogen produced when there is a surplus of variable renewable electricity could in principle be stored and later used to generate heat or to re-generate electricity.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> It can be further transformed into synthetic fuels such as ammonia and methanol.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> Disadvantages of hydrogen fuel include high costs of storage and distribution due to hydrogen's explosivity, its large volume compared to other fuels, and its tendency to embrittle materials.<ref name="Griffiths-20212"/>

Nickel–hydrogen battery

The very long-lived, rechargeable nickel–hydrogen battery developed for satellite power systems uses pressurized gaseousTemplate:NbspH2.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> The International Space Station,<ref>Template:Cite conference</ref> Mars Odyssey<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> and the Mars Global Surveyor<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> are equipped with nickel-hydrogen batteries. In the dark part of its orbit, the Hubble Space Telescope is also powered by nickel-hydrogen batteries, which were finally replaced in MayTemplate:Nbsp2009,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> more than 19Template:Nbspyears after launch and 13Template:Nbspyears beyond their design life.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Semiconductor industry

Hydrogen is employed in semiconductor manufacturing to saturate broken ("dangling") bonds of amorphous silicon and amorphous carbon, which helps in stabilizing the materials' properties.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Hydrogen, introduced as an unintended side-effect of production, acts as a shallow electron donor leading to [[N-type semiconductor|Template:Nowr]] conductivity in ZnO, with important uses in transducers and phosphors.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> Detailed analysis of ZnO and of MgO shows evidence of four and six-fold hydrogen multicentre bonds.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The doping behavior of hydrogen varies with material.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Niche and evolving uses

Beyond than the uses mentioned above, hydrogen is used in smaller scales in the following applications:

- Shielding gas: Hydrogen is used as a shielding gas in welding methods such as atomic hydrogen welding.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

- Coolant: Hydrogen is used as a coolant in large electrical generators due to its high thermal conductivity and low density.<ref>Template:Cite conference</ref> The first hydrogen-cooled turbogenerator went into service using gaseous hydrogen as a coolant in the rotor and the stator inTemplate:Nbsp1937 in Dayton, Ohio.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

- Cryogenic research: Liquid Template:Chem2 is used in cryogenic research, including superconductivity studies.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Food industry: Hydrogen is an authorized food additive (E949)<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> that is used as a packaging gas,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> and also has antioxidant properties.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Leak detection: Pure or mixed with nitrogen (sometimes called forming gas), hydrogen is a tracer gas for detection of minute leaks. Applications can be found in the automotive, chemical, power generation, aerospace, and telecommunications industries;<ref>Template:Cite conference</ref> it also allows for leak testing in food packaging.

- Neutron moderation: Deuterium (hydrogen-2) is used in nuclear fission applications as a moderator to slow neutrons.

- Nuclear fusion fuel: Deuterium is used in nuclear fusion reactions.<ref name="nbb" />

- Isotopic labeling: Deuterium compounds have applications in chemistry and biology in studies of isotope effects on reaction rates.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

- Tritium uses: Tritium (hydrogen-3), produced in nuclear reactors, is used in the production of hydrogen bombs,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> as an isotopic label in the biosciences,<ref name="holte" /> and as a source of beta radiation in radioluminescent paint for instrument dials and emergency signage.<ref name="Traub95" />

Safety and precautions

Template:Main Template:Chembox In hydrogen pipelines and steel storage vessels, hydrogen molecules are prone to reacting with metals, causing hydrogen embrittlement and leaks in the pipeline or storage vessel.<ref name="Li-2022">Template:Cite journalText was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License</ref> Since it is lighter than air, hydrogen does not easily accumulate to form a combustible gas mixture.<ref name="Li-2022" /> However, even without ignition sources, high-pressure hydrogen leakage may cause spontaneous combustion and detonation.<ref name="Li-2022" />

Hydrogen is flammable when mixed even in small amounts with air. Ignition can occur at a volumetric ratio of hydrogen to air as low as 4%.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> In approximately 70% of hydrogen ignition accidents, the ignition source cannot be found, and it is widely believed by scholars that spontaneous ignition of hydrogen occurs.<ref name="Li-2022" />

Hydrogen fire, while being extremely hot, is almost invisible to the human eye, and thus can lead to accidental burns.<ref name="spinoff-2016">Template:Cite web</ref> Hydrogen is non-toxic,<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> but like most gases it can cause asphyxiation in the absence of adequate ventilation.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

See also

- Combined cycle hydrogen power plant

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link (for hydrogen)

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

References

Further reading

Template:Library resources box

External links

- Template:Webarchive (Timothy Jones, Drexel University)

- Hydrogen at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- High temperature hydrogen phase diagram from Burkhard Militzer (University of California, Berkeley)

- Wavefunction of hydrogen at HyperPhysics (Georgia State University)

Template:Subject bar Template:Periodic table (navbox) Template:Hydrogen compounds