Iran–United States relations

Template:Use mdy dates Template:Infobox bilateral relations

Relations between Iran and the United States in modern day are turbulent and have a troubled history. They began in the mid-to-late 19th century, when Iran was known to the Western world as Qajar Persia. Persia was very wary of British and Russian colonial interests during the Great Game. By contrast, the United States was seen as a more trustworthy foreign power, and the Americans Arthur Millspaugh and Morgan Shuster were even appointed treasurers-general by the Shahs of the time. During World War II, Iran was invaded by the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, both US allies, but relations continued to be positive after the war until the later years of the government of Mohammad Mosaddegh, who was overthrown by a coup organized by the Central Intelligence Agency and aided by MI6. This was followed by an era of close alliance between Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's authoritarian regime and the US government,<ref name="Ansari 2006" /> Iran being one of the US's closest allies during the Cold War,<ref>Jenkins, Philip (2006). Decade of Nightmares: The End of the Sixties and the Making of Eighties America: The End of the Sixties and the Making of Eighties America p. 153. Oxford University Press, US. Template:ISBN</ref><ref>Little, Douglas (2009). American Orientalism: The United States and the Middle East since 1945. p. 145. Univ of North Carolina Press. Template:ISBN</ref><ref>Murray, Donette (2009). US Foreign Policy and Iran: American–Iranian Relations Since the Islamic Revolution p. 8. Routledge. Template:ISBN</ref> which was in turn followed by a dramatic reversal and disagreement between the two countries after the 1979 Iranian Revolution.<ref name="Ansari 2006" /><ref name="ABC-CLIO">Template:Cite book</ref>

The two nations have had no formal diplomatic relations since 7 April 1980.<ref name="Ansari 2006">Template:Cite book</ref> Instead, Pakistan serves as Iran's protecting power in the United States, while Switzerland serves as the United States' protecting power in Iran. Contacts are carried out through the Iranian Interests Section of the Pakistani Embassy in Washington, D.C.,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> and the US Interests Section of the Swiss Embassy in Tehran.<ref>Embassy of Switzerland in Iran – Foreign Interests Section Template:Webarchive, Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (page visited on 4 April 2015).</ref> In August 2018, Supreme Leader of Iran Ali Khamenei banned direct talks with the United States.<ref name="Staff">Template:Cite news</ref> According to the US Department of Justice, Iran has since attempted to assassinate US officials and dissidents, including US President Donald Trump.<ref name="JD">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="KD">Template:Cite web</ref>

Iranian explanations for the animosity with the United States include "the natural and unavoidable conflict between the Islamic system" and "such an oppressive power as the United States, which is trying to establish a global dictatorship and further its own interests by dominating other nations and trampling on their rights", as well as the United States support for Israel ("the Zionist entity").<ref>Q&A With the Head of Iran's New America's Desk Template:Webarchive online.wsj.com April 1, 2009</ref><ref>Reading Khamenei: The World View of Iran's Most Powerful Leader, by Karim Sadjadpour March 2008 Template:Webarchive p. 20

It is natural that our Islamic system should be viewed as an enemy and an intolerable rival by such an oppressive power as the United States, which is trying to establish a global dictatorship and further its own interests by dominating other nations and trampling on their rights. It is also clear that the conflict and confrontation between the two is something natural and unavoidable. [Address by Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran, to students at Shahid Beheshti University, May 12, 2003]

</ref> In the West, however, different explanations have been considered,<ref name="Ansari 2006" /> including the Iranian government's need for an external bogeyman to furnish a pretext for domestic repression against pro-democratic forces and to bind the government to its loyal constituency.<ref>The New Republic, Charm Offensive, by Laura Secor, April 1, 2009

To give up this trump card—the non-relationship with the United States, the easy evocation of an external bogeyman—would be costly for the Iranian leadership. It would be a Gorbachevian signal that the revolution is entering a dramatically new phase—one Iran's leaders cannot be certain of surviving in power.

</ref> The United States attributes the worsening of relations to the 1979–81 Iran hostage crisis,<ref name="Ansari 2006" /> Iran's repeated human rights abuses since the Islamic Revolution, different restrictions on using spy methods on democratic revolutions by the US, its anti-Western ideology and its nuclear program.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Since 1995, the United States has had an embargo on trade with Iran.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In 2015, the United States led successful negotiations for a nuclear deal (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) intended to place substantial limits on Iran's nuclear program, including IAEA inspections and limitations on enrichment levels. In 2016, most sanctions against Iran were lifted.<ref>Akbar E. Torbat, Politics of Oil and Nuclear Technology in Iran, Palgrave MacMillan, 2020,</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The Trump administration unilaterally withdrew from the nuclear deal and re-imposed sanctions in 2018, initiating what became known as the "maximum pressure campaign" against Iran.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In response, Iran gradually reduced its commitments under the nuclear deal and eventually exceeded pre-JCPOA enrichment levels.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

According to a 2013 BBC World Service poll, 5% of Americans view Iranian influence positively, with 87% expressing a negative view, the most unfavorable perception of Iran in the world.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> On the other hand, research has shown that most Iranians hold a positive attitude about the American people, though not the US government.<ref>Shahghasemi, E., Heisey, D. R., & Mirani, G. (October 1, 2011). "How do Iranians and U.S. Citizens perceive each other: A systematic review." Template:Webarchive Journal of Intercultural Communication, 27.</ref><ref>Shahghasemi, E., & Heisey, D. R. (January 1, 2009). "The Cross-Cultural Schemata of Iranian-American People Toward Each Other: A Qualitative Approach." Intercultural Communication Studies, 18, 1, 143–160.</ref> According to a 2019 survey by IranPoll, 13% of Iranians have a favorable view of the United States, with 86% expressing an unfavourable view, the most unfavorable perception of the United States in the world.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> According to a 2018 Pew poll, 39% of Americans say that limiting the power and influence of Iran should be a top foreign policy priority.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Relations tend to improve when the two countries have overlapping goals, such as repelling Sunni militants during the Iraq War and the intervention against the Islamic State in the region.<ref>The Middle East and North Africa 2003, eur, 363, 2002</ref>

History

Early relations

American newspapers in the 1720s were uniformly pro-Iranian, especially during the revolt of Afghan emir Mahmud Hotak (Template:Reign) against the Safavid dynasty.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Political relations between Qajar Persia and the United States began when the Shah of Iran, Nassereddin Shah Qajar, officially dispatched Iran's first ambassador, Mirza Abolhasan, to Washington, D.C. in 1856.<ref name="PR">The Middle East and the United States: A Historical and Political Reassessment, David W. Lesch, 2003, Template:ISBN, p. 52</ref> In 1883, Samuel G. W. Benjamin was appointed by the United States as the first official diplomatic envoy to Iran; however, ambassadorial relations were not established until 1944.<ref name="PR" />

-

The US Consulate at Arg e Tabriz sits in the line of fire during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution. While the city was being attacked and bombed by 4,000 Russian troops in December 1911, Howard Baskerville took to arms, helping the people of Iran.

-

Americans wearing jobbeh va kolah (traditional Persian clothes) at the opening of the Majles, January 29, 1924. Mr. McCaskey, Dr. Arthur Millspaugh, and Colonel MacCormack are seen in the photo.

-

Morgan Shuster and US officials at Atabak Palace, Tehran, 1911. Their group was appointed by Iran's parliament to reform and modernize Iran's Department of Treasury and Finances.

-

McCormick Hall, American College of Tehran, circa 1930, chartered by the State University of New York in 1932. Americans also founded Iran's first modern College of Medicine in the 1870s.

-

Joseph Plumb Cochran, American Presbyterian missionary. He is credited as the founder of Iran's first modern medical school.

-

American Memorial School in Tabriz, established in 1881

The US had little interest in Persian affairs, while the US as a trustworthy outsider did not suffer. The Persians again sought the US for help in straightening out its finances after World War I. This mission was opposed by powerful vested interests and eventually was withdrawn with its task incomplete.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

During the Persian Constitutional Revolution in 1909, American Howard Baskerville died in Tabriz while fighting with a militia in a battle against royalist forces.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> After the Iranian parliament appointed United States financier Morgan Shuster as Treasurer General of Iran in 1911, an American was killed in Tehran by gunmen thought to be affiliated with Russian or British interests. Shuster became even more active in supporting the Constitutional Revolution of Iran financially.<ref>Ibid. p. 83</ref>

Arthur Millspaugh, an American economic adviser, was sent to Persia in 1923 as a private citizen to help reform its inefficient administration. His presence was seen by Persians as a means to attract foreign investment and counterbalance European influence. The mission ended in 1928 after Millspaugh fell out of favor with the shah.<ref name=delv>Template:Cite web</ref>

Until World War II, relations between Iran and the United States remained cordial. As a result, many Iranians sympathetic to the Persian Constitutional Revolution came to view the US as a "third force" in their struggle to expel British and Russian dominance in Persian affairs. American industrial and business leaders were supportive of Iran's drive to modernize its economy and to expel British and Russian influence from the country.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Reza Khan, a military officer in Persia’s Cossack Brigade, came to power after leading a British-backed coup in 1921 that overthrew the Qajar Dynasty.<ref>Zirinsky M.P. Imperial Power and dictatorship: Britain and the rise of Reza Shah 1921–1926. International Journal of Middle East Studies. 24, 1992. p. 646</ref><ref>*Foreign Office 371 16077 E2844 dated 8 June 1932.

- The Memoirs of Anthony Eden are also explicit about Britain's role in putting Reza Khan in power.

- Ansari, Ali M. Modern Iran since 1921. Longman. 2003 Template:ISBN pp. 26–31</ref> He later declared himself shah (king) and took the name Reza Pahlavi.<ref name = weisse/> He launched modernization efforts, building a national railway and introducing secular education, while also censoring the press, suppressing unions and parties, and later banning the hijab in favor of Western dress.<ref name= weisse/>

In 1936, Iran withdrew its ambassador in Washington for nearly one year after the publication of an article criticizing Reza Shah in the New York Daily Herald.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

After a dispute over German influence during World War II, Reza Shah was forced to abdicate in 1941 and was succeeded by his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.<ref name= weisse/> During the rest of World War II, Iran became a major conduit for British and American aid to the Soviet Union and an avenue through which over 120,000 Polish refugees and Polish Armed Forces fled the Axis advance.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> At the 1943 Tehran Conference, the Allied "Big Three"—Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill—issued the Tehran Declaration to guarantee the post-war independence and boundaries of Iran. In 1949, the Constituent Assembly of Iran gave the shah the power to dissolve the parliament.<ref name= weisse/>

1953 Iranian coup d'état

Before the coup

Until the outbreak of World War II, the United States had no active policy toward Iran.<ref>Stephen Kinzer All the Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror, John Wiley and Sons, 2003, p. 86</ref> When the Cold War began, the United States was alarmed by the attempt by the Soviet Union to set up separatist states in Iranian Azerbaijan and Kurdistan, as well as its demand for military rights to the Dardanelles in 1946. This fear was enhanced by the loss of China to communism, the uncovering of Soviet spy rings, and the start of the Korean War.<ref>Byrne writing in Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran, Edited by Mark J. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne, Syracuse University Press, 2004, pp. 201, 204–06, 212, 219.</ref>

Prime minister Mossadeq

In 1951, Iran nationalised its oil industry,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> effectively seizing the assets of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC).<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> On 28 April 1951, Mohammad Mosaddegh was elected as Prime Minister by the Parliament of Iran.

The British planned to retaliate by attacking Iran,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> but U.S. President Harry S. Truman pressed Britain to moderate its position in the negotiations and to not invade Iran. American policies fostered a sense in Iran that the United States supported Mossadeq, along with optimism that the oil dispute would soon be resolved through "a series of innovative proposals" that would provide Iran with "significant amounts of economic aid." Mossadeq visited Washington, and the American government made "frequent statements expressing support for him."<ref>Gasiorowski writing in Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran, Edited by Mark J. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne, Syracuse University Press, 2004, p. 273</ref>

At the same time, the United States honored the British embargo and, without Truman's knowledge, the Central Intelligence Agency station in Tehran had been "carrying out covert activities" against Mosaddeq and the National Front "at least since the summer of 1952".<ref>Gasiorowski writing in Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran, Edited by Mark J. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne, Syracuse University Press, 2004, p. 243</ref>

The coup d'état

In 1953, the U.S. and Britain orchestrated a coup to overthrow Iran’s prime minister Mohammad Mosaddeq,<ref name=briefhis>Template:Cite web</ref> fearing communist influence and economic instability after Iran nationalized its oil industry. The coup, led by the CIA and MI6,<ref name=briefhis/> initially failed but succeeded on a second attempt. It reinstalled Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who then received substantial U.S. financial and military support. The U.S. helped establish SAVAK,<ref name=weisse>Template:Cite web</ref> the Shah’s brutal secret police, to maintain his rule. Many liberal Iranians believe that the coup and the subsequent U.S. support for the shah enabled the Shah's arbitrary rule, contributing to the "deeply anti-American character" of the 1979 revolution later.<ref>Gasiorowski, Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran, Edited by Mark J. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne, Syracuse University Press, 2004, p. 261</ref>

After the coup, the United States played a central role in reorganizing Iran’s oil sector. Under U.S. pressure, BP joined a consortium of Western companies to resume Iranian oil exports.<ref name="Ref-B-Vassiliou2009">Marius Vassiliou, Historical Dictionary of the Petroleum Industry : Volume 3]]. p. 269.</ref><ref name="Ref-B-Lauterpacht1973">Lauterpacht, E. International Law Reports. p. 375.</ref> The consortium operated on behalf of the state-owned National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), which retained formal ownership of Iran’s oil and infrastructure.<ref name="Ref-B-Vassiliou2009"/><ref name="Ref-B-Lauterpacht1973"/> While Iran received 50% of the profits, U.S. companies collectively secured 40% of the remaining share.<ref name="Ref-B-Christine2008">Strategies, Markets and Governance: Exploring Commercial and Regulatory Agendas. p. 235.</ref> However, the consortium maintained operational control, barred Iranian oversight of its financial records, and excluded Iranians from its board.<ref name="Stephen2003">Kinzer, All the Shah's Men, (2003), pp. 195–6.</ref> The agreement was part of a wider transition from British to American dominance in the region and worldwide.<ref name="Pluto Press">Template:Cite book</ref>

While initially seen as a Cold War success, the coup later became a source of deep resentment, with critics calling it a blow to democracy and a lasting stain on U.S.-Iran relations.

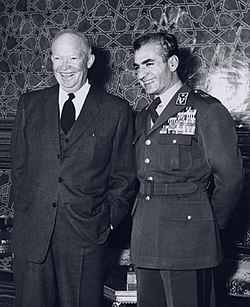

U.S.–Shah alliance

Template:Infobox bilateral relations

Nuclear cooperation

Iran's nuclear program was launched as part of the Atoms for Peace program that was announced by U.S. president Eisenhower in 1953.<ref name="MA" /><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref> The U.S. helped Iran create its nuclear program in 1957 by providing Iran its first nuclear reactor and nuclear fuel, and after 1967 by providing Iran with weapons grade enriched uranium.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name="MA">Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Mustafa Kibaroglu, "Good for the shah, banned for the mullahs: The west and Iran's quest for nuclear power." Middle East Journal 60.2 (2006): 207-232 online Template:Webarchive.</ref> Iran is among the 51 original signatories of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) on July 1, 1968, and its Parliament ratifies the treaty in February 1970.<ref name=delv/> The participation of the U.S. and Western European governments continued until the 1979 Iranian Revolution.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Strategic alliance and geopolitical importance

File:Shah in the US.ogv Iran's border with the Soviet Union, and its position as the largest, most powerful country in the oil-rich Persian Gulf, made Iran a "pillar" of US foreign policy in the Middle East.<ref>Twin Pillars to Desert Storm : America's Flawed Vision in the Middle East from Nixon to Bush by Howard Teicher; Gayle Radley Radley, Harpercollins, 1993</ref> In 1960, Iran joined four other countries to form the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), aiming to challenge the dominance of Western oil companies and reclaim control over national oil resources.<ref name=Kalir>Template:Cite web</ref> In the 1960s and 1970s, Iran's oil revenues grew considerably. Beginning in the mid-1960s, this development "weakened U.S. influence in Iranian politics" while strengthening the Iranian state's power over its own population.Template:Citation needed By the 1970s, surging OPEC profits gave the group substantial leverage over Western economies and elevated Iran’s strategic value as a U.S. ally.<ref name=Kalir/> According to scholar Homa Katouzian, this put the United States "in the contradictory position of being regarded" by the Iranian public "as the chief architect and instructor of the regime," while "its real influence" in domestic Iranian politics and policies "declined considerably".<ref>Katouzian writing in Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran, Edited by Mark J. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne, Syracuse University Press, 2004 p. 23</ref>

Military cooperation and arms sales

James Bill and other historians have said that between 1969 and 1974 U.S. President Richard Nixon actively recruited the Shah as an American puppet and proxy.<ref>James A. Bill, The eagle and the lion: The tragedy of American-Iranian relations (1989).</ref> However, Richard Alvandi argues that it worked the other way around, with the Shah taking the initiative. President Nixon, who had first met the Shah in 1953, regarded him as a westernizing anticommunist statesman who deserved American support now that the British were withdrawing from the region. They met again in 1972 and the Shah agreed to buy large quantities of American military hardware, and took responsibility for ensuring political stability and fighting off Soviet subversion throughout the region.<ref>Roham Alvandi, Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: The United States and Iran in the Cold War (2014)</ref> Permitting Iran to purchase U.S. arms served Cold War objectives by securing the Shah’s alignment with Washington after Iran had briefly explored Soviet alternatives in the 1960s, while also benefiting the American economy.<ref name=blankch>Template:Cite web</ref> However, because of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and the subsequent Arab oil embargo against the United States, oil prices became very high. This enabled the shah to buy more advanced weaponry than U.S. officials had expected, which caused concern in Washington.<ref name = Kalir/>

In the 1970s, approximately 25,000 American technicians were deployed to Iran to maintain military equipment (such as F-14s) that had been sold to the Shah's government.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Cultural and academic relations

Cultural relations between the two countries remained cordial until 1979. Pahlavi University, Sharif University of Technology, and Isfahan University of Technology, three of Iran's top academic universities, were directly modeled on private American institutions such as the University of Chicago, MIT, and the University of Pennsylvania.<ref name="GE">Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Exporting MIT. Stuart W. Leslie and Robert Kargon. Osiris, vol. 21 (2006), pp. 110–30 Template:Doi</ref> The Shah was generous in awarding American universities with financial gifts. For example, the University of Southern California received an endowed chair of petroleum engineering, and a million dollar donation was given to the George Washington University to create an Iranian Studies program.<ref name="GE" />

Prior to the Iranian Revolution of 1979, many Iranian citizens, especially students, resided in the United States and had a positive and welcoming attitude toward America and Americans.<ref name="ABC-CLIO" /> From 1950 to 1979, an estimated 800,000 to 850,000 Americans had visited or lived in Iran, and had often expressed their admiration for the Iranian people.<ref name="ABC-CLIO" />

Ford administration 1974–1977

Under president Gerald Ford, U.S.–Iran relations began to cool. Unlike Richard Nixon, Ford lacked a close personal relationship with the Shah, and his administration took a more cautious stance on nuclear cooperation.<ref name=bic>Template:Cite web</ref> Negotiations over American nuclear exports to Iran faltered as Ford insisted on additional safeguards beyond those required by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which the Shah rejected as an infringement on Iran’s sovereignty.<ref name=oraox>Template:Cite web</ref>

In 1975, President Ford approved a plan allowing Iran to process U.S. nuclear materials and purchase a plutonium reprocessing facility. Henry Kissinger later described it as a commercial deal with an ally, with no discussion of weapons concerns.<ref name = delv/>

Despite continuing Nixon’s arms sales policy, granting Iran wide access to U.S. weapons, Ford faced internal opposition and growing concerns in Congress.<ref name=blankch/> Meanwhile, U.S. officials—particularly Treasury Secretary William Simon grew increasingly critical of the Shah's role in maintaining high oil prices, during a time when surging inflation was driving the U.S. economy toward a recession.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> In 1976, the U.S. covertly supported Saudi Arabia’s move to drive down oil prices, undercutting Iran’s revenues.<ref name=bic/>

The resulting oil price collapse in early 1977 triggered a severe financial crisis in Iran, forcing austerity measures that led to rising unemployment and social unrest. These developments significantly weakened the Shah’s regime and contributed to the conditions that precipitated the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Later declassified documents suggest that key U.S. policymakers underestimated the risks of destabilizing their long-time ally.<ref name=bic/>

Carter administration 1977–1981

In the late 1970s, American President Jimmy Carter emphasized human rights in his foreign policy, but went easy in private with the Shah.<ref>Ghazninian, 2021, p. 280.</ref> By 1977, Iran had garnered unfavorable publicity in the international community for its bad human rights record.<ref>Abrahamian, Iran (1982), pp. 498–99.</ref> That year, the Shah responded to Carter's "polite reminder" by granting amnesty to some prisoners and allowing the Red Cross to visit prisons. Through 1977, liberal opposition formed organizations and issued open letters denouncing the Shah's regime.<ref>Abrahamian, Iran (1982), pp. 501–03.</ref><ref name="JC">Template:Cite web</ref>

Carter angered anti-Shah Iranians with a New Year's Eve 1978 toast to the Shah in which he said:

Under the Shah's brilliant leadership Iran is an island of stability in one of the most troublesome regions of the world. There is no other state figure whom I could appreciate and like more.<ref>Geopolitical Aspects of Islamization hosted by ca-c.org Template:Webarchive</ref>

Observers disagree over the nature of United States policy toward Iran under Carter as the Shah's regime crumbled. According to historian Nikki Keddie, the Carter administration followed "no clear policy" on Iran.<ref>Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), p. 235.</ref> The US National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski "repeatedly assured Pahlavi that the U.S. backed him fully". At the same time, officials in the State Department believed the revolution was unstoppable.<ref>Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), pp. 235–36.</ref> After visiting the Shah in 1978, Secretary of the Treasury W. Michael Blumenthal complained of the Shah's emotional collapse.<ref>Shawcross, The Shah's Last Ride (1988), p. 21.</ref> Brzezinski and Energy Secretary James Schlesinger were adamant in assurances that the Shah would receive military support.

Sociologist Charles Kurzman argues that the Carter administration was consistently supportive of the Shah and urged the Iranian military to stage a "last-resort coup d'état".<ref>Kurzman, Charles, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, Harvard University Press, 2004, p. 157</ref><ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Iranian Revolution

Template:Further The Iranian/Islamic Revolution (1978–1979) ousted the Shah and replaced him with the anti-American Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.<ref>This Day In History Shah flees Iran Retrieved 4 September 2023</ref> The United States government State Department and intelligence services "consistently underestimated the magnitude and long-term implications of this unrest".<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Six months before the revolution culminated, the CIA had produced a report stating that "Iran is not in a revolutionary or even a 'prerevolutionary' situation."<ref>US House of Representatives, Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, Iran. Evaluation of U.S. Intelligence Performance Prior to November 1978. Staff Report, Washington, DC, p. 7 Template:Webarchive.</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Revolutionary students feared the power of the United States, particularly the CIA, to overthrow a new Iranian government. One source of this concern was a book by CIA agent Kermit Roosevelt Jr. titled Countercoup: The Struggle for Control of Iran. Many students had read excerpts from the book and thought that the CIA would attempt to implement this countercoup strategy.<ref>Heikal, Iran: The Untold Story (1982), p. 23. "It was abundantly clear to me that the students were obsessed with the idea that the Americans might be preparing to mount another counter-coup. Memories of 1953 were uppermost in their minds. They all knew about Kermit Roosevelt's book Countercoup, and most of them had read extracts from it. Although, largely owing to intervention by the British, who were anxious that the part they and the oil company had played in organizing the coup should not become known, this book had been withdrawn before publication, a few copies of it had got out and been duplicated."</ref>

Khomeini referred to America as the "Great Satan"<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> and instantly got rid of the Shah's prime minister, replacing him with politician Mehdi Bazargan. Until this point, the Carter administration was still hoping for normal relationships with Iran, sending its National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski.

The Islamic revolutionaries wished to extradite and execute the ousted Shah, and Carter refused to give him any further support or help return him to power. The Shah, suffering from terminal cancer, requested entry into the United States for treatment. The American embassy in Tehran opposed the request, as they were intent on stabilizing relations between the new interim revolutionary government of Iran and the United States.<ref name="JC" /> However, President Carter agreed to let the Shah in, after pressure from Henry Kissinger, Nelson Rockefeller and other pro-Shah political figures. Iranians' suspicion that the Shah was actually trying to conspire against the Iranian Revolution grew; thus, this incident was often used by the Iranian revolutionaries to justify their claims that the former monarch was an American puppet, and this led to the storming of the American embassy by radical students allied with Khomeini.<ref name="JC" />

The hostage crisis and its consequences

On November 4, 1979, Iranian student revolutionaries, with Ayatollah Khomeini’s approval, seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran, holding 52 American diplomats hostage for 444 days in response to the U.S. granting asylum to the deposed Shah. The crisis, seen in Iran as a stand against American influence and in the U.S. as a violation of diplomatic law, led to failed rescue attempts and lasting damage to Iran-U.S. relations. Six Americans escaped via the CIA-Canadian "Canadian Caper" operation, later dramatized in the film Argo.

As a response to the seizure of the embassy, Carter banned Iranian oil imports,<ref name=iranpri>Template:Cite web</ref> followed by his Executive Order 12170 froze about $12 billion in Iranian assets,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> including bank deposits, gold and other properties. They were the first of a number of international sanctions against Iran.<ref name="scholar.harvard.edu">Haidar, J.I., 2017."Sanctions and Exports Deflection: Evidence from Iran Template:Webarchive," Economic Policy (Oxford University Press), April 2017, Vol. 32(90), pp. 319-355.</ref>

The crisis ended with the Algiers Accords in January 1981. Under the terms of the agreement and Iran's compliance, the hostaged diplomats were allowed to leave Iran. One of the chief provisions of the Accords was that the United States would lift the freeze on Iranian assets and remove trade sanctions.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The agreement also established the Iran–U.S. Claims Tribunal in The Hague to handle claims brought by Americans against Iran, as well as claims by Iran against Americans and the former shah.<ref name=iranpri/> The diplomatic ties remain severed, with Switzerland and Pakistan handling each country's interests.

Reagan administration 1981–1989

Iran–Iraq War

Template:See also American intelligence and logistical support played a crucial role in arming Iraq in the Iran–Iraq War. However, Bob Woodward states that the United States gave information to both sides, hoping "to engineer a stalemate".<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> In search for a new set or order in this region, Washington adopted a policy designed to contain both sides economically and militarily.<ref name="Simbar 2006 73–87">Template:Cite journal</ref> During the second half of the Iran–Iraq War, the Reagan administration pursued several sanction bills against Iran; on the other hand, it established full diplomatic relations with Saddam Hussein's Ba'athist government in Iraq by removing it from the US list of State Sponsors of Terrorism in 1984.<ref name="Simbar 2006 73–87" /> According to the U.S. Senate Banking Committee, the administrations of Presidents Reagan and George H. W. Bush authorized the sale to Iraq of numerous dual-use items, including poisonous chemicals and deadly biological viruses, such as anthrax and bubonic plague.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> The Iran–Iraq War ended with both agreeing to a ceasefire in 1988.

1983: Hezbollah bombings

Template:Main Hezbollah, an Iran-backed Shi'ite Islamist group, has carried out multiple anti-American attacks, including the 1983 U.S. Embassy bombing in Beirut (killing 63, including 17 Americans), the Beirut barracks bombing (killing 241 U.S. Marines), and the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing. U.S. courts have ruled Iran responsible for these attacks, with evidence showing Hezbollah operated under Iran’s direction and that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei authorized the Khobar Towers bombing.

1983: Anti-communist purge

According to the Tower Commission report:

In 1983, the U.S. helped bring to the attention of Tehran the threat inherent in the extensive infiltration of the government by the communist Tudeh Party and Soviet or pro-Soviet cadres in the country. Using this information, the Khomeini government took measures, including mass executions, that virtually eliminated the pro-Soviet infrastructure in Iran.<ref>Template:Cite book Available online here.</ref>

Iran–Contra Affair

Template:Further To evade congressional rules regarding an arms embargo, officials in President Ronald Reagan's administration arranged in the mid-1980s to sell arms to Iran in an attempt to improve relations and obtain their influence in the release of hostages held in Lebanon. Oliver North of the National Security Council diverted proceeds from the arms sale to fund anti-Marxist Contra rebels in Nicaragua.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="reaganspeech">Template:Cite web</ref> In November 1986, Reagan issued a statement denying the arms sales.<ref>Template:Cite web </ref> One week later, he confirmed that weapons had been transferred to Iran, but denied that they were part of an exchange for hostages.<ref name="reaganspeech" /> Later investigations by Congress and an independent counsel disclosed details of both operations and noted that documents relating to the affair were destroyed or withheld from investigators by Reagan administration officials on national security grounds.<ref name="Excerpts from Iran-Contra Report">Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite book</ref> The revelation that profits from the arms sales had been illegally funneled to the Contras created a major political scandal for Reagan.<ref name= briefhis/>

United States attack of 1988

Template:Main In 1988, the U.S. launched Operation Praying Mantis in retaliation for Iran mining the Persian Gulf during the Iran–Iraq War, following Operation Nimble Archer. It was the largest American naval operation since World War II, with strikes that destroyed two Iranian oil platforms and sank a major warship. Iran sought reparations at the International Court of Justice, but the court dismissed the claim. The attack helped pressure Iran into agreeing to a ceasefire with Iraq later that year.

1988: Iran Air Flight 655

Template:Main On July 3, 1988, during the Iran–Iraq War, the U.S. Navy's USS Vincennes mistakenly shot down Iran Air Flight 655, a civilian Airbus A300B2, killing 290 people.<ref name= briefhis/> The U.S. initially claimed the aircraft was a warplane and outside the civilian air corridor, but later acknowledged the downing was an accident in a combat zone. Iran, however, argued it was gross negligence and sued the U.S. in the International Court of Justice, resulting in compensation for the victims' families. The U.S. expressed regret, calling it a tragic accident, while the Vincennes crew received military honors.

George H. W. Bush administration 1989–1993

Newly elected U.S. president George H. W. Bush announced a "goodwill begets goodwill" gesture in his inaugural speech on 20 January 1989. The Bush administration urged President of Iran Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani to use Iran's influence in Lebanon to obtain the release of the remaining US hostages held by Hezbollah. Bush indicated there would be a reciprocal gesture toward Iran by the United States.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Relevant background events during the first year of Bush's administration include the ending of the Iran–Iraq War and the death of Ayatollah Khomeini.<ref name =timeline>Template:Cite web</ref> Khomeini believed he had a sacred duty to purge Iran of what he saw as Western corruption and moral decay, aiming to restore the country to religious purity under Islamic theocratic rule.<ref name = timeline/> Khomeini was succeeded by Ali Khamenei.

In 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait,<ref name =timeline/> which led to the Gulf War. The U.S. persuaded Iran to vote in favor of UN resolution 678 - which issued an ultimatum for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait - by promising to lift its objections to a series of World Bank loans. The first loan, totaling $250 million, was approved just one day before the ground assault on Iraq began.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The war ended on 28 February 1991.<ref name =timeline/>

Clinton administration 1993–2001

Template:See also In April 1995, a total oil and trade embargo on dealings with Iran by American companies was imposed by Bill Clinton.<ref name = weisse/> This ended trade, which had been growing following the end of the Iran–Iraq War.<ref>Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), p. 265</ref> The next year, the American Congress passed the Iran-Libya Sanctions act, designed to prevent other countries from making large investments in Iranian energy. The act was denounced by the European CC as invalid.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Khatami and Iranian reformers

In January 1998, newly elected Iranian President Mohammad Khatami called for a "dialogue of civilizations" with the United States. In the interview, Khatami invoked Alexis de Tocqueville's Democracy in America to explain similarities between American and Iranian quests for freedom.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> American Secretary of State Madeleine Albright responded positively. This brought free travel between the countries as well as an end to the American embargo of Iranian carpets and pistachios. Relations then stalled due to opposition from Iranian conservatives and American preconditions for discussions, including changes in Iranian policy on Israel, nuclear energy, and support for terrorism.<ref>Keddie, Modern Iran, (2003) p. 272</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Inter-Parliamentary (Congress-to-Majlis) informal talks

On August 31, 2000, four United States Congress members, Senator Arlen Specter, Representative Bob Ney, Representative Gary Ackerman, and Representative Eliot L. Engel held informal talks in New York City with several Iranian leaders. The Iranians included Mehdi Karroubi, speaker of the Majlis of Iran (Iranian Parliament); Maurice Motamed, a Jewish member of the Majlis; and three other Iranian parliamentarians.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

George W. Bush administration 2001–2009

Template:Main Iran–United States relations during the George W. Bush administration (2001–2009) were marked by heightened tensions, mutual distrust, and periodic attempts at limited engagement. Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, Iran initially was sympathetic with the United States.<ref name= president>P.I.R.I News Headlines (Tue 80/07/03 A.H.S). The Official Site of the Office of the President of Iran. Official website of the President of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 25 September 2001. Permanent Archived Link. Original page and URL are not available online now. (Website's Homepage at that time (Title: Presidency of The Islamic Republic of Iran, The Official Site))</ref> However, relations deteriorated sharply after President George W. Bush labeled Iran part of the "Axis of Evil" in 2002, accusing the country of pursuing weapons of mass destruction that posed a threat to the U.S.<ref name=suterror>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name=fax>Template:Cite web</ref> In 2003, Swiss Ambassador Tim Guldimann relayed an unofficial proposal to the U.S. outlining a possible "grand bargain" with Iran. He claimed it was developed in cooperation with Iran, but it lacked formal Iranian endorsement, and the Bush administration did not pursue the offer.<ref name=Guldi>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name="Kessler">Template:Cite news</ref><ref name="Rubin">Template:Cite web</ref>

Between 2003 and 2008, Iran accused the United States of repeatedly violating its territorial sovereignty through drone incursions,<ref name="washdrones">U.S. Uses Drones to Probe Iran For Arms Template:Webarchive, February 13, 2005, The Washington Post</ref><ref name="nytdronesresponse">Iran Protests U.S. Aerial Drones Template:Webarchive, November 8, 2005, The Washington Post</ref> covert operations, and support for opposition groups.<ref name="seymourhershone">Template:Cite magazine</ref><ref name="kucinich">Kucinich Questions The President On US Trained Insurgents In Iran: Sends Letter To President Bush Template:Webarchive, Dennis Kucinich, April 18, 2006</ref> In August 2005, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became Iran's president. During his presidency, attempts at dialogue, including a personal letter to President Bush,<ref name=Ahmaletter>"Timeline: US-Iran ties." BBC News. Retrieved 29-10-2006.</ref> were dismissed by U.S. officials,<ref name="WPLetter">Vick, Karl. "No Proposals in Iranian's Letter to Bush, U.S. Says." Template:Webarchive The Washington Post. Retrieved 29-10-2006.</ref> while public tensions grew over Iran’s nuclear program, U.S. foreign policy, and Ahmadinejad’s controversial remarks at international forums. The United States intensified covert operations against Iran, including alleged support for militant groups such as PEJAK and Jundullah, cross-border activities, and expanded CIA and Special Forces missions. Iran was repeatedly accused by the U.S. of arming and training Iraqi insurgents, including Shiite militias and groups linked to Hezbollah, with American officials citing captured weapons, satellite images, and detainee testimonies. During this period, additional flashpoints included the U.S. raid on Iran's consulate in Erbil, sanctions targeting Iranian financial institutions, a naval dispute in the Strait of Hormuz, and the public disclosure of covert action plans against Iran.

Obama administration 2009–2017

Template:Main Iran–United States relations during the Obama administration (2009–2017) were defined by a shift from confrontation to cautious engagement, culminating in the landmark nuclear agreement of 2015.

At the start of Obama's presidency, both sides exchanged public messages signaling a possible thaw, with Iran voicing long-standing grievances<ref name="npr_halfway">Template:Cite web</ref> and the United States calling for mutual respect and responsibility.<ref name= newbegin>Template:Cite news</ref> However, after Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's disputed re-election in 2009, which sparked mass protests and allegations of fraud, the United States responded with skepticism and concern.<ref name=skep>Template:Cite news</ref> In late 2011 and early 2012, Iran threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz<ref name= Hormuz11>Template:Cite news</ref> and warned a U.S. aircraft carrier not to return to the Persian Gulf. The U.S. rejected the warning and maintained its naval presence, while experts doubted Iran’s ability to sustain a blockade.<ref name=Cordesman>Template:Citation</ref><ref name=Talmadge>Template:Cite journal</ref>

The 2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani, seen as a moderate,<ref name= moderate>Template:Cite news</ref> marked a shift in tone, with his outreach at the UN and a historic phone call with Obama signaling renewed diplomatic engagement.<ref name=call>Obama speaks with Iranian President Rouhani Template:Webarchive NBC News 27 September 2013</ref><ref>Obama talks to Rouhani: First direct conversation between American and Iranian presidents in 30 years National Post 27 September 2013</ref> While high-level contact resumed and symbolic gestures were exchanged, conservative backlash in Iran highlighted internal divisions over rapprochement.<ref name=protests>Template:Cite web</ref> In 2015, the United States and other world powers reached the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran, under which Iran agreed to limit its nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief.<ref name=deal>Template:Cite web</ref> The agreement marked a major diplomatic achievement for the Obama administration, though it faced skepticism in Congress<ref name="LoBianco Tatum 2015">Template:Cite web</ref> and mixed public support in the U.S.

Despite the JCPOA, tensions between the United States and Iran persisted over ballistic missile tests, continued U.S. sanctions, and European business hesitancy due to fear of U.S. penalties.<ref name= nucdeal>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name=summana>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name=EUblock>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name= DispRes>Template:Cite journal</ref> The administration also faced criticism for its handling of these issues, both from Iran<ref name = IranImp>Template:Cite web</ref> and from political opponents.

First Trump administration 2017–2021

Iran–United States relations during the first Trump administration (2017–2021) were marked by a sharp policy shift from Obama's engagement-oriented approach. Trump began with a travel ban affecting Iranian citizens,<ref name =travelban>Template:Cite news</ref> and withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). A broader maximum pressure campaign followed, with over 1,500 sanctions targeting Iran’s financial, oil, and shipping sectors, as well as foreign firms doing business with Iran, severely damaging its economy.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> The effort aimed to isolate Iran but met with strong resistance—even from U.S. allies—and often left Washington diplomatically isolated.<ref name=Laraj>{{#invoke:Cite|news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/20/us/politics/trump-iran-nuclear-deal.html |access-date=November 11, 2021 |title=Instead of Isolating Iran, U.S. Finds Itself on the Outside Over Nuclear Deal |first1=Lara |last1=Jakes |first2=David E. |last2=Sanger |newspaper=The New York Times |date=August 20, 2020}}</ref>

Iran responded by threatening to resume unrestricted uranium enrichment;<ref name = limit>Template:Cite news</ref> rejecting negotiations with the Trump administration,<ref name= nowar>Template:Cite news</ref> and intensified rhetoric. Tensions escalated in 2019 with U.S. intelligence reports of Iranian threats,<ref name=explained>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name=strike>Template:Cite news</ref> attacks on oil tankers, the downing of a U.S. drone by Iran,<ref name=shotdrone>Template:Cite news</ref> and suspected Iranian strikes on Saudi oil facilities.<ref name= oilwar>Template:Cite web</ref> President Trump called off retaliatory strikes,<ref name="NYTCocked">Template:Cite web</ref> using for cyberattacks and additional sanctions instead.<ref name=cyber>Template:Cite web</ref>

A major escalation followed a December 2019 rocket attack on the K-1 Air Basein Iraq,<ref name=killedcont>Template:Cite news</ref> which led to American airstrikes on Iranian-backed militias<ref name=BRubin>Template:Cite news</ref> and a retaliatory attack on the U.S. embassy in Baghdad.<ref name= BEmbassy>Template:Cite news</ref> On 3 January 2020, the U.S. assassinated Iranian General Qasem Soleimani in a drone strike,<ref name=slain>Template:Cite web</ref> prompting Iranian missile attacks on U.S. bases in Iraq and heightened fears of war. The crisis deepened with the accidental downing of a Ukrainian passenger plane by Iranian forces and continued through early 2020 with retaliatory strikes and threats.<ref name=RFE>Template:Cite web</ref>

Later in 2020, Iran blamed U.S. sanctions for limiting its COVID-19 response.<ref name=irancovid>Template:Cite news</ref> They launched a military satellite,<ref name=rocket>Template:Cite web</ref> and were later accused of interfering in the U.S. presidential election<ref name= election>Template:Cite news</ref> and proxy attacks.<ref name="cnn-taliban">Template:Cite news</ref> Relations ended under Trump with continued hostility and unresolved disputes.

Biden administration 2021–2025

Template:Main Iran–United States relations during the Biden administration (2021–2025) were shaped by efforts to revive the 2015 nuclear agreement alongside ongoing regional tensions, sanctions, cyberattacks, and proxy conflicts. Early in Joe Biden’s presidency, U.S. officials expressed interest in returning to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA),<ref name=blunder>Template:Cite news</ref> but negotiations in Vienna eventually stalled.<ref name="1953-2023 timeline">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name= stalling>Template:Cite web</ref> Iran increased uranium enrichment and imposed retaliatory sanctions,<ref name="1953-2023 timeline"/><ref name=15sanct>Template:Cite news</ref> while the U.S. imposed new sanctions over missile programs, oil exports, and human rights abuses.<ref name=Blinkdeal>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name= Moscsanct>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name=IranChina>Template:Cite news</ref>

Tensions persisted throughout this era, marked by recurring proxy attacks on U.S. bases,<ref name=Kataib>Template:Cite news</ref> which intensified following the outbreak of the Gaza war in late 2023,<ref name=proiran>Template:Cite news</ref> and by subsequent American retaliatory strikes.<ref name = 65milit>Template:Cite web</ref> The period also saw disputes over the assassination of Qasem Soleimani,<ref name="Motamedi">Template:Cite web</ref><ref name=avengeUS>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name=offercon>Template:Cite news</ref> and military escalations across the Gulf region.<ref name=ErbilUS>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name=Iranseizes>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name=1000US>Template:Cite web</ref> In 2023, a breakthrough occurred with a U.S.–Iran prisoner swap and the release of frozen Iranian funds,<ref name= 6Bdeal>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name= humani>„The US moves to advance a prisoner swap deal with Iran and release $6 billion in frozen funds" AP News (September 12, 2023) accessed September 13, 2023.</ref><ref name = breakth>Template:Cite news</ref> though indirect diplomacy remained fragile.<ref name= EUhoped>Template:Cite news</ref> Iran was later accused of interfering in the 2024 U.S. presidential election through cyber operations and AI disinformation.<ref name= Iranhack>Template:Cite web</ref><ref name = Iranmail>Template:Cite news</ref><ref name= AI3lines>Template:Cite news</ref> Alleged assassination plots targeting Donald Trump and dissidents on U.S. soil further strained relations.<ref name="KD"/> By late 2024, relations remained adversarial, marked by unresolved security disputes and growing mistrust.

Second Trump administration 2025–present

In February 2025, Trump said he had given the military and his advisors instructions to obliterate Iran if he were to be assassinated.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> He signed the return of the Maximum pressure campaign against the Iranian government.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Trump called for talks for a nuclear peace agreement.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In February 7 prayer, Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei dismissed negotiations and warned Iranian government not to make a deal with US.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> February 9, Trump said that he would rather make a deal with Iranians than let them be bombed by Israel.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In March 2025, Khamenei stated he did not intend to go to negotiations with Trump.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> IRGC General Salami threatened United States military with devastation.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Trump threatened he would hold Iranian regime to blame for any shots fired by Houthis.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Putin and Trump reached an agreement that Iran should never be in a position to destroy Israel.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In April, Ali Larijani, advisor to Khamenei, threatened Trump that Iran would make nuclear weapons.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> Islamic Republic military allegedly had recommended a preemptively strike on US military bases.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In April President Trump stated that Iranians want direct negotiations.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> US–Iran negotiations began on 12 April 2025.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In April 2025, U.S. Congressmen Joe Wilson and Jimmy Panetta introduced a 'Free Iraq from Iran' bill. The legislation mandates the development of a comprehensive U.S. strategy to irreversibly dismantle Iran-backed militias, including the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), and calls for the suspension of U.S. assistance to Iraq until these militias are fully removed. The bill also imposes sanctions on Iraqi political and military figures aligned with Iran, and provides support for Iraqi citizens and independent media to expose abuses committed by these militias. Its primary objective is to restore Iraq’s sovereignty and reduce Iranian dominance without resorting to direct military intervention.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

In his speech his May 2025 trip to Middle East Trump called out the Iranians as the most destructive force and denounced the Iran leaders for having managed to be turning green fertile farmland and rolling blackouts calling on it to make a choice between war and violence and making a deal.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> On June 7, 2025, the U.S. Treasury Department imposed sanctions on 10 individuals and 27 entities, including Iranian nationals and firms based in the UAE and Hong Kong. These targets include the Zarringhalam brothers, accused of laundering billions via shell companies tied to the IRGC and Iran’s Central Bank. The funds reportedly supported Iran’s nuclear and missile programs, oil sales, and militant proxies.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Relations further worsened after Iranian authorities threatened to attack U.S. and allied bases in the Middle East if the former were to involve itself in the Iran–Israel war,<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> after which the U.S. intervened in the Israeli attacks and bombed key Iranian nuclear sites.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

On June 21, 2025, the U.S., under the orders of President Trump, bombed 3 Iranian nuclear enrichment sites, Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan, briefly joining the Iran-Israel war.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> Following the attacks, Iran pulled out and suspended nuclear talks indefinitely.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Economic relations

Template:See also Trade between Iran and the United States reached $623 million in 2008. According to the United States Census Bureau, American exports to Iran reached $93 million in 2007 and $537 million in 2008. American imports from Iran decreased from $148 million in 2007 to $86 million in 2008.<ref name="iran-daily.com">http://www.nitc.co.ir/iran-daily/1387/3300/html/economy.htm Template:Dead link</ref> This data does not include trade conducted through third countries to circumvent the trade embargo. It has been reported that the United States Treasury Department has granted nearly 10,000 special licenses to American companies over the past decade to conduct business with Iran.<ref>"Report: U.S. Treasury approved business with Iran." AP, 24 December 2010.</ref>

US exports to Iran includeTemplate:When cigarettes (US$73 million); corn (US$68 million); chemical wood pulp, soda or sulfate (US$64 million); soybeans (US$43 million); medical equipment (US$27 million); vitamins (US$18 million); and vegetable seeds (US$12 million).<ref name="iran-daily.com" />

In May 2013, US President Barack Obama lifted a trade embargo of communications equipment and software to non-government Iranians.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> In June 2013, the Obama administration expanded its sanctions against Iran, targeting its auto industry and, for the first time, its currency.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

According to a 2014 study by the National Iranian American Council, sanctions cost the US over $175 billion in lost trade and 279,000 lost job opportunities.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

According to Business Monitor International: Template:Blockquote

On 22 April 2019, under the Trump administration, the U.S. demanded that buyers of Iranian oil stop purchases or face economic penalties, announcing that the six-month sanction exemptions for China, India, Japan, South Korea and Turkey instated a year prior would not be renewed and would end by 1 May. The move was seen as an attempt to completely stifle Iran's oil exports. Iran insisted the sanctions were illegal and that it had attached "no value or credibility" to the waivers. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said President Trump's decision not to renew the waivers showed his administration was "dramatically accelerating our pressure campaign in a calibrated way that meets our national security objectives while maintaining well supplied global oil markets".<ref>Template:Cite news</ref> On 30 April, Iran stated it would continue to export oil despite U.S. pressure.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

On 8 May 2019, exactly one year after the Trump administration withdrew the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the U.S. imposed a new layer of duplicate sanctions on Iran, targeting its metal exports, a sector that generates 10 percent of its export revenue. The move came amid escalating tension in the region and just hours after Iran threatened to start enriching more uranium if it did not get relief from U.S. measures that are crippling its economy. The Trump administration has said the sanctions will only be lifted if Iran fundamentally changes its behavior and character.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

On 24 June 2019, following continued escalations in the Strait of Hormuz, President Donald Trump announced new targeted sanctions against Iranian and IRGC leadership, including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and his office. IRGC targets included Naval commander Alireza Tangsiri, Aerospace commander Amir Ali Hajizadeh, and Ground commander Mohammad Pakpour, and others.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref> U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said the sanctions will block "billions" in assets.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

The US Treasury Department Financial Crimes Enforcement Network imposed a measure that further prohibits the US banking system from use by an Iranian bank, thereby requiring US banks to step up due diligence on the accounts in their custody.<ref name="fincen_5th_measure_iran">Template:Cite news</ref>

The US Department of Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) blacklisted four Iranian metal sector organizations along with their foreign subsidiaries, on 23 July 2020. One German subsidiary and three in the United Arab Emirates – owned and controlled by Iran's biggest steel manufacturer, Mobarakeh Steel Company – were also blacklisted by Washington for yielding millions of dollars for Iran's aluminum, steel, iron, and copper sectors. The sanctions froze all US assets controlled by the companies in question and further prohibited Americans from associating with them.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

On October 8, 2020, the U.S. Treasury Department placed sanctions on 18 Iranian banks. Any American connection to these banks is to be blocked and reported to the Office of Foreign Assets Control, and, 45 days after the sanctions take effect, anyone transacting with these banks may "be subject to an enforcement action." Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said the goal was to pressure Iran to end nuclear activities and terrorist funding.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

On 30 October 2020, it was revealed that the US had "seized Iranian missiles shipped to Yemen", and it had "sold 1.1 million barrels of previously seized Iranian oil that was bound for Venezuela" in two shipments: the Liberia-flagged Euroforce and Singapore-flagged Maersk Progress, and sanctioned 11 new Iranian entities.<ref name="snlgm">Template:Cite news</ref>

See also

- Foreign relations of Iran

- Foreign relations of the United States

- Embassy of Iran, Washington, D.C.

- Embassy of the United States, Tehran

- Ambassadors of Iran to the United States

- Ambassadors of the United States to Iran

References

Further reading

- Afrasiabi, Kaveh L. and Abbas Maleki, Iran's Foreign Policy After September 11. Booksurge, 2008.

- Aliyev, Tural. "The Evaluation of the Nuclear Weapon Agreement with Iran in the Perspective of the Difference Between Obama and Trump's Administration." R&S-Research Studies Anatolia Journal 4.1: 30–40. online

- Alvandi, Roham. Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: The United States and Iran in the Cold War (Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Template:Cite book

- Blight, James G. and Janet M. Lang, et al. Becoming Enemies: U.S.-Iran Relations and the Iran-Iraq War, 1979–1988. (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014).

- Chitsazian, Mohammad Reza, and Seyed Mohammad Ali Taghavi. "An Iranian Perspective on Iran–US Relations: Idealists Versus Materialists." Strategic Analysis 43.1 (2019): 28–41. online

- Clinton, Hillary Rodham. Hard Choices (2014) under Obama; pp 416–446.

- Collier, David R. Democracy and the nature of American influence in Iran, 1941-1979 (Syracuse University Press, 2017.)

- Cooper, Andrew Scott. The Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle East, 2011, Template:ISBN.

- Cordesman, Anthony H. "Iran and US Strategy: Looking beyond the JCPOA." (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2021). online

- Cottam, Richard W. "Human rights in Iran under the Shah." Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 12 (1980): 121+ online.

- Cottam, Richard W. Iran and the United States: A Cold War Case Study (1988) on the fall of the Shah

- Crist, David. The Twilight War: The Secret History of America's Thirty-Year Conflict with Iran, Penguin Press, 2012.

- Cronin, Stephanie. The making of modern Iran: state and society under Riza Shah, 1921-1941 (Routledge, 2003).

- Emery, Christian. US Foreign Policy and the Iranian Revolution: The Cold War Dynamics of Engagement and Strategic Alliance. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Gasiorowski, Mark J. "U.S. Perceptions of the Communist Threat in Iran during the Mossadegh Era." Journal of Cold War Studies 21.3 (2019): 185–221. online

- Ghazvinian, John. America and Iran: A History, 1720 to the Present (2021), a major scholarly history excerpt

- Harris, David., The Crisis: the President, the Prophet, and the Shah—1979 and the Coming of Militant Islam, (2004).

- Heikal, Mohamed Hassanein. Iran: The Untold Story: An Insider's Account of America's Iranian Adventure and Its Consequences for the Future. New York: Pantheon, 1982.

- Johns, Andrew L. "The Johnson Administration, the Shah of Iran, and the Changing Pattern of US-Iranian Relations, 1965–1967: 'Tired of Being Treated like a Schoolboy'." Journal of Cold War Studies 9.2 (2007): 64–94. online

- Kashani-Sabet, Firoozeh (2023). Heroes to Hostages: America and Iran, 1800–1988. Cambridge University Press.

- Katzman, Kenneth. Iran: Politics, Human Rights, and U.S. Policy. (2017).

- Kinch, Penelope. "The Iranian Crisis and the Dynamics of Advice and Intelligence in the Carter Administration." Journal of Intelligence History 6.2 (2006): 75–87.

- Ledeen, Michael A., and William H. Lewis. "Carter and the fall of the Shah: The inside story." Washington Quarterly 3.2 (1980): 3–40.

- Leverett, Flynt: Going to Tehran: Why the United States Must Come to Terms with the Islamic Republic (Picador, 2013)

- Mabon, Simon. "Muting the trumpets of sabotage: Saudi Arabia, the US and the quest to securitize Iran." British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 45.5 (2018): 742–759. online

- Moens, Alexander. "President Carter's Advisers and the Fall of the Shah." Political Science Quarterly 106.2 (1991): 211–237. online

- Offiler, Ben. US Foreign Policy and the Modernization of Iran: Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon and the Shah (Springer, 2015).

- Offiler, Ben. ""A spectacular irritant": US–Iranian relations during the 1960s and the World's Best Dressed Man." The Historian (2021): 1-23, about Khaibar Khan Gudarzian. online

- Rostam-Kolayi, Jasamin. "The New Frontier Meets the White Revolution: The Peace Corps in Iran, 1962‒76." Iranian Studies 51.4 (2018): 587–612.

- Template:Cite book

- Saikal, Amin. Iran Rising: The Survival and Future of the Islamic Republic (2019)

- Shannon, Michael K. "American–Iranian Alliances: International Education, Modernization, and Human Rights during the Pahlavi Era," Diplomatic History 39 (Sept. 2015), 661–88.

- Shannon, Michael K. Losing Hearts and Minds: American-Iranian Relations and International Education during the Cold War (2017) excerpt

- Template:Cite book

- Summitt, April R. "For a white revolution: John F. Kennedy and the Shah of Iran." Middle East Journal 58.4 (2004): 560–575. online

- Torbat, Akbar E. "A Glance at US Policies toward Iran: Past A_GLANCE_AT_US_POLICIES_TOWARD_IRAN and Present," Journal of Iranian Research and Analysis, vol. 20, no. 1 (April 2004), pp. 85–94.

- Waehlisch, Martin. "The Iran-United States Dispute, the Strait of Hormuz, and International Law," Yale Journal of International Law, Vol. 37 (Spring 2012), pp. 23–34.

- Wise, Harold Lee. Inside the Danger Zone: The U.S. Military in the Persian Gulf 1987–88. (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2007).

- Wright, Steven. The United States and Persian Gulf Security: The Foundations of the War on Terror. (Ithaca Press, 2007).

Historiography

- Schayegh, Cyrus. "'Seeing Like a State': An Essay on the Historiography of Modern Iran." International Journal of Middle East Studies 42#1 (2010): 37–61.

- Shannon, Kelly J. "Approaching the Islamic World". Diplomatic History 44.3 (2020): 387–408, historical focus on US views of Iran.

- Shannon, Matthew K. "Reading Iran: American academics and the last shah." Iranian Studies 51.2 (2018): 289–316. onlineTemplate:Dead linkTemplate:Cbignore

External links

- Timeline – The New York Times

- Virtual Embassy of the United States in Iran

- Articles and debates about Iran by Council on Foreign Relations

- US-Iran Relations by parstimes.com

- United States Policy toward Iran: a Dossier

- Videos

- On The Same Page: America's Middle East Allies and Regional Threats - Foundation for Defense of Democracies — 1/15/2021

Template:Iran–United States relations Template:Foreign relations of Iran Template:Foreign relations of the United States Template:Portal bar Template:Authority control