Titania (moon)

Template:Short description Template:Distinguish Template:Featured article Template:Infobox planet

Titania (Template:IPAc-en) is the largest moon of Uranus and the eighth-largest moon in the Solar System, with a diameter of 1,578 km (981 mi). Discovered by William Herschel in 1787, it is named after the queen of the fairies in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream. Its orbit lies inside Uranus's magnetosphere.

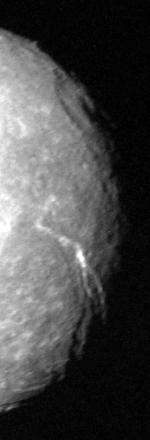

Titania consists of approximately equal amounts of ice and rock, and is probably differentiated into a rocky core and an icy mantle. A layer of liquid water may be present at the core–mantle boundary. Its surface, which is relatively dark and slightly red in color, appears to have been shaped by both impacts and endogenic processes. Although Titania is covered with numerous impact craters reaching up to 326 kilometres (203 mi) in diameter, it is less heavily cratered than Oberon, the outermost of Uranus's five large moons. It may have undergone an early endogenic resurfacing event which obliterated its older, heavily cratered surface. Its surface is cut by a system of enormous canyons and scarps, the result of the expansion of its interior during the later stages of its evolution. Like all major moons of Uranus, Titania probably formed from an accretion disk which surrounded the planet just after its formation.

Infrared spectroscopy conducted from 2001 to 2005 revealed the presence of water ice as well as frozen carbon dioxide on Titania's surface, suggesting it may have a tenuous carbon dioxide atmosphere with a surface pressure of about 10 nanopascals (10−13 bar). Measurements during Titania's occultation of a star put an upper limit on the surface pressure of any possible atmosphere at 1–2 mPa (10–20 nbar). The Uranian system has been studied up close only once, by the spacecraft Voyager 2 in January 1986. It took several images of Titania, which allowed mapping of about 40% of its surface.

Discovery and naming

Titania was discovered by William Herschel on January 11, 1787, the same day he discovered Uranus's second largest moon, Oberon.<ref name="Herschel 1787" /><ref name="Herschel 1788" /> He later reported the discoveries of four more satellites,<ref name="Herschel 1798" /> although they were subsequently revealed as spurious.<ref name="Struve1848" /> For nearly the next 50 years, Titania and Oberon would not be observed by any instrument other than William Herschel's,<ref name="Herschel 1834" /> although the moon can be seen from Earth with a present-day high-end amateur telescope.<ref name="Newton Teece 1995" />

All of Uranus's moons are named after characters created by William Shakespeare or Alexander Pope. The name Titania was taken from the Queen of the Fairies in A Midsummer Night's Dream.<ref name="Kuiper 1949" /> The names of all four satellites of Uranus then known were suggested by Herschel's son John in 1852, at the request of William Lassell,<ref name="Lassell 1852" /> who had discovered the other two moons, Ariel and Umbriel, the year before.<ref name="Lassell 1851" /> It is uncertain if Herschel devised the names, or if Lassell did so and then sought Herschel's permission.<ref name=podcast>Template:Cite web</ref>

Titania was initially referred to as "the first satellite of Uranus", and in 1848 was given the designation Template:Nowrap by William Lassell,<ref name="Lassell 1848" /> although he sometimes used William Herschel's numbering (where Titania and Oberon are II and IV).<ref name="Lassell 1850" /> In 1851 Lassell eventually numbered all four known satellites in order of their distance from the planet by Roman numerals, and since then Titania has been designated Template:Nowrap.<ref name="Lassell, letter 1851" />

Shakespeare's character's name is pronounced Template:IPAc-en, but the moon is often pronounced Template:IPAc-en, by analogy with the familiar chemical element titanium.<ref name="Webster" /> The adjectival form, Titanian, is homonymous with that of Saturn's moon Titan. The name Titania is ancient Greek for "Daughter of the Titans".

Planetary moons other than Earth's were never given symbols in the astronomical literature. Denis Moskowitz, a software engineer who designed most of the dwarf planet symbols, proposed a T (the initial of Titania) combined with the low globe of Jérôme Lalande's Uranus symbol as the symbol of Titania (![]() ). This symbol is not widely used.<ref name=moons>Template:Cite web</ref>

). This symbol is not widely used.<ref name=moons>Template:Cite web</ref>

Orbit

Titania orbits Uranus at the distance of about Template:Convert, being the second farthest from the planet among its five major moons after Oberon.Template:Efn Titania's orbit has a small eccentricity and is inclined very little relative to the equator of Uranus.<ref name="orbit" /> Its orbital period is around 8.7 days, coincident with its rotational period. In other words, Titania is a synchronous or tidally locked satellite, with one face always pointing toward the planet.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" />

Titania's orbit lies completely inside the Uranian magnetosphere.<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" /> This is important, because the trailing hemispheres of satellites orbiting inside a magnetosphere are struck by magnetospheric plasma, which co-rotates with the planet.<ref name="Ness Acuña et al. 1986" /> This bombardment may lead to the darkening of the trailing hemispheres, which is actually observed for all Uranian moons except Oberon (see below).<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" />

Because Uranus orbits the Sun almost on its side, and its moons orbit in the planet's equatorial plane, they (including Titania) are subject to an extreme seasonal cycle. Both northern and southern poles spend 42 years in a complete darkness, and another 42 years in continuous sunlight, with the sun rising close to the zenith over one of the poles at each solstice.<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" /> The Voyager 2 flyby coincided with the southern hemisphere's 1986 summer solstice, when nearly the entire southern hemisphere was illuminated. Once every 42 years, when Uranus has an equinox and its equatorial plane intersects the Earth, mutual occultations of Uranus's moons become possible. In 2007–2008 a number of such events were observed including two occultations of Titania by Umbriel on August 15 and December 8, 2007.<ref name="Miller & Chanover 2009" /><ref name="Arlot Dumas et al. 2008" />

Composition and internal structure

Titania is the largest and most massive Uranian moon, the eighth most massive moon in the Solar System, and the 20th largest object in the Solar System.Template:Efn Its density of 1.68 g/cm3,<ref name="Jacobson Campbell et al. 1992" /> which is much higher than the typical density of Saturn's satellites, indicates that it consists of roughly equal proportions of water ice and dense non-ice components;<ref name="Hussmann Sohl et al. 2006" /> the latter could be made of rock and carbonaceous material including heavy organic compounds.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" /> The presence of water ice is supported by infrared spectroscopic observations made in 2001–2005, which have revealed crystalline water ice on the surface of the moon.<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" /> Water ice absorption bands are slightly stronger on Titania's leading hemisphere than on the trailing hemisphere. This is the opposite of what is observed on Oberon, where the trailing hemisphere exhibits stronger water ice signatures.<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" /> The cause of this asymmetry is not known, but it may be related to the bombardment by charged particles from the magnetosphere of Uranus, which is stronger on the trailing hemisphere (due to the plasma's co-rotation).<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" /> The energetic particles tend to sputter water ice, decompose methane trapped in ice as clathrate hydrate and darken other organics, leaving a dark, carbon-rich residue behind.<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" />

Except for water, the only other compound identified on the surface of Titania by infrared spectroscopy is carbon dioxide, which is concentrated mainly on the trailing hemisphere.<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" /> The origin of the carbon dioxide is not completely clear. It might be produced locally from carbonates or organic materials under the influence of the solar ultraviolet radiation or energetic charged particles coming from the magnetosphere of Uranus. The latter process would explain the asymmetry in its distribution, because the trailing hemisphere is subject to a more intense magnetospheric influence than the leading hemisphere. Another possible source is the outgassing of the primordial CO2 trapped by water ice in Titania's interior. The escape of CO2 from the interior may be related to the past geological activity on this moon.<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" />

Titania may be differentiated into a rocky core surrounded by an icy mantle.<ref name="Hussmann Sohl et al. 2006" /> If this is the case, the radius of the core Template:Convert is about 66% of the radius of the moon, and its mass is around 58% of the moon's mass—the proportions are dictated by moon's composition. The pressure in the center of Titania is about 0.58 GPa (5.8 kbar).<ref name="Hussmann Sohl et al. 2006" /> The current state of the icy mantle is unclear. If the ice contains enough ammonia or other antifreeze, Titania may have a subsurface ocean at the core–mantle boundary. The thickness of this ocean, if it exists, is up to Template:Convert and its temperature is around 190 K (close to the water–ammonia eutectic temperature of 176 K).<ref name="Hussmann Sohl et al. 2006" /> However the present internal structure of Titania depends heavily on its thermal history, which is poorly known. Recent studies suggest, contrary to earlier theories, that Uranus largest moons like Titania in fact could have active subsurface oceans.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Surface features

Among Uranus's moons, Titania is intermediate in brightness between the dark Oberon and Umbriel and the bright Ariel and Miranda.<ref name="Karkoschka, Hubble 2001" /> Its surface shows a strong opposition surge: its reflectivity decreases from 35% at a phase angle of 0° (geometrical albedo) to 25% at an angle of about 1°. Titania has a relatively low Bond albedo of about 17%.<ref name="Karkoschka, Hubble 2001" /> Its surface is generally slightly red in color, but less red than that of Oberon.<ref name="Bell1991" /> However, fresh impact deposits are bluer, while the smooth plains situated on the leading hemisphere near Ursula crater and along some grabens are somewhat redder.<ref name="Bell1991" /><ref name="Plescia 1987" /> There may be an asymmetry between the leading and trailing hemispheres;<ref name="Buratti1991" /> the former appears to be redder than the latter by 8%.Template:Efn However, this difference is related to the smooth plains and may be accidental.<ref name="Bell1991" /> The reddening of the surfaces probably results from space weathering caused by bombardment by charged particles and micrometeorites over the age of the Solar System.<ref name="Bell1991" /> However, the color asymmetry of Titania is more likely related to accretion of a reddish material coming from outer parts of the Uranian system, possibly, from irregular satellites, which would be deposited predominately on the leading hemisphere.<ref name="Buratti1991" />

Scientists have recognized three classes of geological feature on Titania: craters, chasmata (canyons) and rupes (scarps).<ref name="USGS: Titania Nomenclature" /> The surface of Titania is less heavily cratered than the surfaces of either Oberon or Umbriel, which means that the surface is much younger.<ref name="Plescia 1987" /> The crater diameters reach 326 kilometers for the largest known crater, Gertrude<ref name="USGS: Titania: Gertrude" /> (there can be also a degraded basin of approximately the same size).<ref name="Plescia 1987" /> Some craters (for instance, Ursula and Jessica) are surrounded by bright impact ejecta (rays) consisting of relatively fresh ice.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" /> All large craters on Titania have flat floors and central peaks. The only exception is Ursula, which has a pit in the center.<ref name="Plescia 1987" /> To the west of Gertrude there is an area with irregular topography, the so-called "unnamed basin", which may be another highly degraded impact basin with the diameter of about Template:Convert.<ref name="Plescia 1987" />

Titania's surface is intersected by a system of enormous faults, or scarps. In some places, two parallel scarps mark depressions in the satellite's crust,<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" /> forming grabens, which are sometimes called canyons.<ref name="Croft 1989" /> The most prominent among Titania's canyons is Messina Chasma, which runs for about Template:Convert from the equator almost to the south pole.<ref name="USGS: Titania Nomenclature" /> The grabens on Titania are Template:Convert wide and have a relief of about 2–5 km.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" /> The scarps that are not related to canyons are called rupes, such as Rousillon Rupes near Ursula crater.<ref name="USGS: Titania Nomenclature" /> The regions along some scarps and near Ursula appear smooth at Voyager's image resolution. These smooth plains were probably resurfaced later in Titania's geological history, after the majority of craters formed. The resurfacing may have been either endogenic in nature, involving the eruption of fluid material from the interior (cryovolcanism), or, alternatively it may be due to blanking by the impact ejecta from nearby large craters.<ref name="Plescia 1987" /> The grabens are probably the youngest geological features on Titania—they cut all craters and even smooth plains.<ref name="Croft 1989" />

The geology of Titania was influenced by two competing forces: impact crater formation and endogenic resurfacing.<ref name="Croft 1989" /> The former acted over the moon's entire history and influenced all surfaces. The latter processes were also global in nature, but active mainly for a period following the moon's formation.<ref name="Plescia 1987" /> They obliterated the original heavily cratered terrain, explaining the relatively low number of impact craters on the moon's present-day surface.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" /> Additional episodes of resurfacing may have occurred later and led to the formation of smooth plains.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" /> Alternatively smooth plains may be ejecta blankets of the nearby impact craters.<ref name="Croft 1989" /> The most recent endogenous processes were mainly tectonic in nature and caused the formation of the canyons, which are actually giant cracks in the ice crust.<ref name="Croft 1989" /> The cracking of the crust was caused by the global expansion of Titania by about 0.7%.<ref name="Croft 1989" />

Atmosphere

The presence of carbon dioxide on the surface suggests that Titania may have a tenuous seasonal atmosphere of CO2, much like that of the Jovian moon Callisto.Template:Efn<ref name="Widemann Sicardy et al. 2009" /> Other gases, like nitrogen or methane, are unlikely to be present, because Titania's weak gravity could not prevent them from escaping into space. At the maximum temperature attainable during Titania's summer solstice (89 K), the vapor pressure of carbon dioxide is about 300 μPa (3 nbar).<ref name="Widemann Sicardy et al. 2009" />

On September 8, 2001, Titania occulted a bright star (HIP 106829) with a visible magnitude of 7.2; this was an opportunity to both refine Titania's diameter and ephemeris, and to detect any extant atmosphere. The data revealed no atmosphere to a surface pressure of 1–2 mPa (10–20 nbar); if it exists, it would have to be far thinner than that of Triton or Pluto.<ref name="Widemann Sicardy et al. 2009" /> This upper limit is still several times higher than the maximum possible surface pressure of the carbon dioxide, meaning that the measurements place essentially no constraints on parameters of the atmosphere.<ref name="Widemann Sicardy et al. 2009" />

The peculiar geometry of the Uranian system causes the moons' poles to receive more solar energy than their equatorial regions.<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" /> Because the vapor pressure of CO2 is a steep function of temperature,<ref name="Widemann Sicardy et al. 2009" /> this may lead to the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the low-latitude regions of Titania, where it can stably exist on high albedo patches and shaded regions of the surface in the form of ice. During the summer, when the polar temperatures reach as high as 85–90 K,<ref name="Widemann Sicardy et al. 2009" /><ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" /> carbon dioxide sublimates and migrates to the opposite pole and to the equatorial regions, giving rise to a type of carbon cycle. The accumulated carbon dioxide ice can be removed from cold traps by magnetospheric particles, which sputter it from the surface. Titania is thought to have lost a significant amount of carbon dioxide since its formation 4.6 billion years ago.<ref name="Grundy Young et al. 2006" />

Origin and evolution

Titania is thought to have formed from an accretion disc or subnebula; a disc of gas and dust that either existed around Uranus for some time after its formation or was created by the giant impact that most likely gave Uranus its large obliquity.<ref name="Mousis 2004" /> The precise composition of the subnebula is not known; however, the relatively high density of Titania and other Uranian moons compared to the moons of Saturn indicates that it may have been relatively water-poor.Template:Efn<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" /> Significant amounts of nitrogen and carbon may have been present in the form of carbon monoxide and N2 instead of ammonia and methane.<ref name="Mousis 2004" /> The moons that formed in such a subnebula would contain less water ice (with CO and N2 trapped as a clathrate) and more rock, explaining their higher density.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" />

Titania's accretion probably lasted for several thousand years.<ref name="Mousis 2004" /> The impacts that accompanied accretion caused heating of the moon's outer layer.<ref name="Squyres Reynolds et al. 1988" /> The maximum temperature of around Template:Convert was reached at a depth of about Template:Convert.<ref name="Squyres Reynolds et al. 1988" /> After the end of formation, the subsurface layer cooled, while the interior of Titania heated due to decay of radioactive elements present in its rocks.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" /> The cooling near-surface layer contracted, while the interior expanded. This caused strong extensional stresses in the moon's crust leading to cracking. Some of the present-day canyons may be a result of this. The process lasted for about 200 million years,<ref name="Hillier & Squyres 1991" /> implying that any endogenous activity ceased billions of years ago.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" />

The initial accretional heating together with continued decay of radioactive elements were probably strong enough to melt the ice if some antifreeze like ammonia (in the form of ammonia hydrate) or salt was present.<ref name="Squyres Reynolds et al. 1988" /> Further melting may have led to the separation of ice from rocks and formation of a rocky core surrounded by an icy mantle. A layer of liquid water (ocean) rich in dissolved ammonia may have formed at the core–mantle boundary.<ref name="Hussmann Sohl et al. 2006" /> The eutectic temperature of this mixture is Template:Convert.<ref name="Hussmann Sohl et al. 2006" /> If the temperature dropped below this value, the ocean would have subsequently frozen. The freezing of the water would have caused the interior to expand, which may have been responsible for the formation of the majority of the canyons.<ref name="Plescia 1987" /> However, the present knowledge of Titania's geological evolution is quite limited. Whereas more up to date analysis suggest that larger moons of Uranus are not only capable of having active subsurface oceans; but in fact; presumed to have subterranean oceans beneath them.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref><ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Exploration

So far the only close-up images of Titania have been from the Voyager 2 probe, which photographed the moon during its flyby of Uranus in January 1986. Since the closest distance between Voyager 2 and Titania was only Template:Convert,<ref name="Stone 1987" /> the best images of this moon have a spatial resolution of about 3.4 km (only Miranda and Ariel were imaged with a better resolution).<ref name="Plescia 1987" /> The images cover about 40% of the surface, but only 24% was photographed with the precision required for geological mapping. At the time of the flyby, the southern hemisphere of Titania (like those of the other moons) was pointed towards the Sun, so the northern (dark) hemisphere could not be studied.<ref name="Smith Soderblom et al. 1986" />

No other spacecraft has ever visited the Uranian system or Titania. One possibility, now discarded, was to send Cassini on from Saturn to Uranus in an extended mission. Another mission concept proposed was the Uranus orbiter and probe concept, evaluated around 2010. Uranus was also examined as part of one trajectory for a precursor interstellar probe concept, Innovative Interstellar Explorer.

The Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission architecture was identified as the highest priority for a NASA Flagship mission by the 2023–2032 Planetary Science Decadal Survey. The science questions motivating this prioritization include questions about the Uranian satellites' bulk properties, internal structure, and geologic history.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref> A Uranus orbiter<ref>Mark Hofstadter, "Ice Giant Science: The Case for a Uranus Orbiter", Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, Report to the Decadal Survey Giant Planets Panel, 24 August 2009</ref> had previously been listed as the third priority for a NASA Flagship mission by the 2013–2022 Planetary Science Decadal Survey.<ref>Stephen Clark "Uranus, Neptune in NASA's sights for new robotic mission", Spaceflight Now, August 25, 2015</ref>

See also

Notes

References

External links

- Template:Cite web

- NASA archive of publicly released Titania images

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Titania page (including labelled maps of Titania) at Views of the Solar System

- Titania nomenclature from the USGS Planetary Nomenclature web site

Template:Uranus Template:Navbox Template:Solar System moons (compact) Template:Portal bar Template:Authority control