Spanish phonology

Template:Short description Template:Self-reference Template:IPA notice Template:Spanish language This article is about the phonology and phonetics of the Spanish language. Unless otherwise noted, statements refer to Castilian Spanish, the standard dialect used in Spain on radio and television.<ref>Template:Citation</ref><ref>Template:Citation</ref><ref>Template:Citation</ref><ref>Template:Cite encyclopedia</ref> For historical development of the sound system, see History of Spanish. For details of geographical variation, see Spanish dialects and varieties.

Phonemic representations are written inside slashes (Template:IPA), while phonetic representations are written in brackets (Template:IPA).

Consonants

Template:Anchor The phonemes Template:IPA, Template:IPA, and Template:IPA are pronounced as voiced stops only after a pause, after a nasal consonant, or—in the case of Template:IPA—after a lateral consonant; in all other contexts, they are realized as approximants (namely Template:IPA, hereafter represented without the downtacks) or fricatives.<ref>The continuant allophones of Spanish Template:IPA have been traditionally described as voiced fricatives (e.g. Template:Harvcoltxt, who (in §100) describes the air friction of Template:IPA as being "tenue y suave" ('weak and smooth'); Template:Harvcoltxt; Template:Harvcoltxt; and Template:Harvcoltxt, who describes Template:IPA as being "...with audible friction"). However, they are more often described as approximants in recent literature, such as Template:Harvcoltxt; Template:Harvcoltxt; and Template:Harvcoltxt. The difference hinges primarily on air turbulence caused by extreme narrowing of the opening between articulators, which is present in fricatives and absent in approximants. Template:Harvcoltxt displays a sound spectrogram of the Spanish word abogado showing an absence of turbulence for all three consonants.</ref><ref name="carrera257"/>

The phoneme Template:IPA is distinguished from Template:IPA only in some areas of Spain (mostly northern and rural) and South America (mostly highland). Other accents of Spanish, comprising the majority of speakers, have lost the palatal lateral as a distinct phoneme and have merged historical Template:IPA into Template:IPA: this is called yeísmo.

The realization of the phoneme Template:IPA varies greatly by dialect.<ref name="HualdeQuasiPhonemic">Template:Cite conference</ref> In Castilian Spanish, its allophones in word-initial position include the palatal approximant Template:IPAblink, the palatal fricative Template:IPAblink, the palatal affricate Template:IPAblink and the palatal stop Template:IPAblink.<ref name="HualdeQuasiPhonemic"/> After a pause, a nasal, or a lateral, it may be realized as an affricate (Template:IPA);<ref name="carrera258">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref name="Trager">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> in other contexts, /ʝ/ is generally realized as an approximant Template:IPAblink. In Rioplatense Spanish, spoken across Argentina and Uruguay, the voiced palato-alveolar fricative Template:IPAblink is used in place of Template:IPA and Template:IPA, a feature called "zheísmo".Template:Sfnp In the last few decades, it has further become popular, particularly among younger speakers in Argentina and Uruguay, to de-voice Template:IPA to Template:IPAblink ("sheísmo").Template:Sfnp<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

The phone Template:IPAblink occurs as a deaffricated pronunciation of Template:IPA in some other dialects (most notably, Northern Mexican Spanish, informal Chilean Spanish, and some Caribbean and Andalusian accents).<ref name="cotton15"/> Otherwise, Template:IPA is a marginal phoneme that occurs only in loanwords or certain dialects; many speakers have difficulty with this sound, tending to replace it with Template:IPA or Template:IPA.

Many young Argentinians have no distinct Template:IPA phoneme and use the Template:IPA sequence instead, thus making no distinction between Template:Lang and Template:Lang (both Template:IPA).<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Most varieties spoken in Spain, including those prevalent on radio and television, have a phonemic contrast between Template:IPA and Template:IPA. Speakers with this contrast (which is called distinción) use Template:IPA in words spelled with Template:Angbr, such as Template:Lang 'house' Template:IPA, and Template:IPA in words spelled with Template:Angbr or Template:Angbr (when it occurs before Template:Angbr or Template:Angbr), such as Template:Lang 'hunt' Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> However, speakers in parts of southern Spain, the Canary Islands, and all of Latin America lack this distinction, merging both consonants as Template:IPA. The use of Template:IPA in place of Template:IPA is called seseo. Some speakers in southernmost Spain (especially coastal Andalusia) merge both consonants as Template:IPAblink: this is called ceceo, since Template:IPA sounds similar to Template:IPA. This "ceceo" is not entirely unknown in the Americas, especially in coastal Peru.

The exact pronunciation of Template:IPA varies widely by dialect: it may be pronounced as [h] or omitted entirely ([∅]), especially at the end of a syllable.<ref name="Núñez-Méndez">Template:Cite journal</ref>

The phonemes Template:IPA and Template:IPA are laminal denti-alveolar (Template:IPA).<ref name="carrera257">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> The phoneme Template:IPA becomes dental Template:IPA before denti-alveolar consonants,<ref name="carrera258"/> while Template:IPA remains interdental Template:IPA in all contexts.<ref name="carrera258"/>

Before front vowels Template:IPA, the velar consonants Template:IPA (including the lenited allophone of Template:IPA) are realized as post-palatal Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

According to some authors,<ref>For example Template:Harvcoltxt, Template:Harvcoltxt and Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Template:IPA is post-velar or uvular in the Spanish of northern and central Spain.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt, cited in Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Others<ref>such as Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> describe Template:IPA as velar in European Spanish, with a uvular allophone (Template:IPAblink) appearing before Template:IPA and Template:IPA (including when Template:IPA is in the syllable onset as Template:IPA).<ref name="carrera258"/>

A common pronunciation of Template:IPA in nonstandard speech is the voiceless bilabial fricative Template:IPAblink, so that Template:Lang is pronounced Template:IPA rather than Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref name="cotton15">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In some Extremaduran, western Andalusian, and American varieties, this softened realization of Template:IPA, when it occurs before the non-syllabic allophone of Template:IPA (Template:IPAblink), is subject to merger with Template:IPA; in some areas the homophony of Template:Lang/Template:Lang is resolved by replacing Template:Lang with Template:Lang or Template:Lang.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref name="Penny2000p122">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Consonant neutralizations and assimilations

Some of the phonemic contrasts between consonants in Spanish are lost in certain phonological environments, especially at the end of a syllable. In these cases, the phonemic contrast is said to be neutralized.

Sonorants

Nasals and laterals

At the start of a syllable, there is a contrast between three nasal consonants: Template:IPA, Template:IPA, and Template:IPA (as in cama 'bed', cana 'grey hair', caña 'sugar cane'), but at the end of a syllable, this contrast is generally neutralized, as nasals assimilate to the place of articulation of the following consonant<ref name="carrera258"/>—even across a word boundary.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Within a morpheme, a syllable-final nasal is obligatorily pronounced with the same place of articulation as a following stop consonant, as in banco Template:IPA.<ref name="Morris 1998 pages=17–18">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> An exception to coda nasal place assimilation is the sequence Template:IPA that can be found in the middle of words such as Template:Lang, Template:Lang, Template:Lang.<ref name="Hualde 2022 page=793"/><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Only one nasal consonant, Template:IPA, can occur at the end of words in native vocabulary.<ref name="Hualde 2022 page=793">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> When followed by a pause, Template:IPA is pronounced by most speakers as alveolar Template:IPA (though in Caribbean varieties, it may be pronounced instead as Template:IPAblink, or omitted with nasalization of the preceding vowel).<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> When followed by another consonant, morpheme-final Template:IPA shows variable place assimilation depending on speech rate and style.<ref name="Morris 1998 pages=17–18"/>

Word-final Template:IPA and Template:IPA in stand-alone loanwords or proper nouns may be adapted to Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

Similarly, Template:IPA assimilates to the place of articulation of a following coronal consonant, i.e. a consonant that is interdental, dental, alveolar, or palatal.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref name="Dalbor 1980">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In dialects that maintain the use of Template:IPA, there is no contrast between Template:IPA and Template:IPA in coda position, and syllable-final Template:IPA appears only as an allophone of Template:IPA in rapid speech.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

| nasal | lateral | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word | IPA | gloss | word | IPA | gloss |

| invierno | Template:Audio-IPA | 'winter' | |||

| ánfora | Template:Audio-IPA | 'amphora' | |||

| encía | Template:Audio-IPA | 'gum' | alzar | Template:Audio-IPA | 'to raise' |

| antes | Template:Audio-IPA | 'before' | alto | Template:Audio-IPA | 'tall' |

| ancha | Template:Audio-IPA | 'wide' | colcha | Template:Audio-IPA | 'quilt' |

| cónyuge | Template:Audio-IPA | 'spouse' | |||

| rincón | Template:Audio-IPA | 'corner' | |||

| enjuto | Template:Audio-IPA | 'thin' | |||

Rhotics

The alveolar trill Template:IPAblink and the alveolar tap Template:IPAblink are in phonemic contrast word-internally between vowels (as in carro 'car' vs. caro 'expensive'), but are otherwise in complementary distribution, as long as syllable division is taken into account: the tap occurs after any syllable-initial consonant, while the trill occurs after any syllable-final consonant.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Only the trill can occur at the start of a word (e.g. el rey 'the king', la reina 'the queen') or after a syllable-final (coda) consonant (e.g. alrededor, enriquecer, desratizar).

Only the tap can occur after a word-initial obstruent consonant (e.g. tres 'three', frío 'cold').

Either a trill or a tap can occur word-medially after Template:IPA, Template:IPA, Template:IPA depending on whether the rhotic consonant is pronounced in the same syllable as the preceding obstruent (forming a complex onset cluster) or in a separate syllable (with the obstruent forming the coda of the preceding syllable). The tap is found in words where no morpheme boundary separates the obstruent from the following rhotic consonant, such as sobre 'over', madre 'mother', ministro 'minister'. The trill is only found in words where the rhotic consonant is preceded by a morpheme boundary and thus a syllable boundary, such as subrayar, ciudadrealeño, postromántico;<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> compare the corresponding word-initial trills in raya 'line', Ciudad Real "Ciudad Real", and romántico "Romantic".

In syllable-final position before consonants inside a word, the tap is more frequent, but the trill can also occur (especially in emphatic<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> or oratorical<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> style) with no semantic difference—thus arma ('weapon') may be either Template:IPA (tap) or Template:IPA (trill).<ref name="Harris">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In word-final position the rhotic is usually:

- either a tap or a trill when followed by a consonant or a pause, as in amoTemplate:IPA paterno ('paternal love'), the former being more common;<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

- a tap when followed by a vowel-initial word, as in amoTemplate:IPA eterno ('eternal love').

Morphologically, a word-final rhotic always corresponds to the tapped Template:IPA in related words. Thus the word Template:Lang 'smell' is related to Template:Lang 'smells, smelly' and not to Template:Lang.<ref name="HualdeQuasiPhonemic"/>

When two rhotics occur consecutively across a word or prefix boundary, they result in one trill, so that da rocas ('they (sg.) give rocks') and dar rocas ('to give rocks') are either neutralized or distinguished by a longer trill in the latter phrase.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt.</ref>

The tap/trill alternation has prompted a number of authors to postulate a single underlying rhotic; the intervocalic contrast then results from gemination (e.g. tierra Template:IPA > Template:IPA 'earth').<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Obstruents

The phonemes Template:IPA, Template:IPA,<ref name="carrera258"/> and Template:IPA<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> may be voiced before voiced consonants, as in Template:Lang ('jasmine') Template:IPA, Template:Lang ('feature') Template:IPA, and Template:Lang ('Afghanistan') Template:IPA. There is a certain amount of free variation in this, so Template:Lang can be pronounced Template:IPA or Template:IPA. This Template:IPA is consistently fricative, whereas the Template:IPA allophone of Template:IPA varies between a fricative and an approximant, like Template:IPA, Template:IPA and Template:IPA. In strict IPA, they would be written as Template:IPA and Template:IPA, respectively.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Such voicing may occur across word boundaries, causing Template:Lang ('merry Christmas') Template:IPA to be pronounced Template:IPA.<ref name="Núñez-Méndez"/> In one region of Spain, the area around Madrid, word-final Template:IPA is sometimes pronounced Template:IPA, especially in a colloquial pronunciation of the city's name, which results being pronounced as Template:Audio-IPA.<ref name=salgado>Template:Cite book</ref> More so, in some words now spelled with -z- before a voiced consonant, the phoneme Template:IPA is in fact diachronically derived from original Template:IPA realization of the Template:IPA phoneme. For example, Template:Lang comes from Old Spanish Template:Lang, and Template:Lang comes from Old Spanish Template:Lang, from Latin Template:Lang.<ref>Template:Cite journal</ref>

Both in casual and formal speech, there is no phonemic contrast between voiced and voiceless consonants placed in syllable-final position. The merged phoneme is typically pronounced as a relaxed, voiced fricative or approximant,<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> although a variety of other realizations are also possible. So the clusters -Template:Lang- and -Template:Lang- in the words Template:Lang and Template:Lang are pronounced exactly the same way:

Similarly, the spellings Template:Lang and Template:Lang are often merged in pronunciation, as well as -Template:Lang- and -Template:Lang-:

- Template:Lang Template:Audio-IPA

- Template:Lang Template:Audio-IPA

- Template:Lang Template:Audio-IPA

- Template:Lang Template:Audio-IPA

Semivowels

Traditionally, the palatal consonant phoneme Template:IPA is considered to occur only as a syllable onset,<ref name="Martínez Celdrán 2004 208">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> whereas the palatal glide Template:IPA that can be found after an onset consonant in words like bien is analyzed as a non-syllabic version of the vowel phoneme Template:IPA<ref name="Bowen 1955 236">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> (which forms part of the syllable nucleus, being pronounced with the following vowel as a rising diphthong). The approximant allophone of Template:IPA, which can be transcribed as Template:IPA, differs phonetically from Template:IPA in the following respects: Template:IPA has a lower F2 amplitude, is longer, can be replaced by a palatal fricative Template:IPAblink in emphatic pronunciations, and is unspecified for rounding (e.g. viuda Template:Audio-IPA 'widow' vs. ayuda Template:Audio-IPA 'help').<ref name="Martínez Celdrán 2004 208"/>

After a consonant, the surface contrast between Template:IPA and Template:IPA depends on syllabification, which in turn is largely predictable from morphology: the syllable boundary before Template:IPA corresponds to the morphological boundary after a prefix.<ref name="HualdeQuasiPhonemic"/> A contrast is therefore possible after any consonant that can end a syllable, as illustrated by the following minimal or near-minimal pairs: after Template:IPA (italiano Template:IPA 'Italian' vs. y tal llano Template:IPA 'and such a plain'<ref name="HualdeQuasiPhonemic"/>), after Template:IPA (enyesar Template:Audio-IPA 'to plaster' vs. aniego Template:Audio-IPA 'flood'<ref name="Trager" />) after Template:IPA (desierto Template:IPA 'desert' vs. deshielo Template:IPA 'thawing'<ref name="HualdeQuasiPhonemic"/>), after Template:IPA (abierto Template:IPA 'open' vs. abyecto Template:IPA 'abject'<ref name="HualdeQuasiPhonemic"/><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>).

Although there is dialectal and idiolectal variation, speakers may also exhibit a contrast in phrase-initial position.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt cite the minimal pair ya visto Template:IPA ('I already dress') vs. y ha visto Template:IPA ('and he has seen')</ref> In Argentine Spanish, the change of Template:IPA to a fricative realized as Template:IPA has resulted in clear contrast between this consonant and the glide Template:IPA; the latter occurs as a result of spelling pronunciation in words spelled with Template:Angbr, such as Template:Lang Template:IPA 'grass' (which thus forms a minimal pair in Argentine Spanish with the doublet Template:Lang Template:IPA 'maté leaves').<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

There are some alternations between the two, prompting scholars like Template:Harvcoltxt<ref>cited in Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> to postulate an archiphoneme Template:IPA, so that ley Template:Audio-IPA would be transcribed phonemically as Template:IPA and leyes Template:Audio-IPA as Template:IPA.

In a number of varieties, including some American ones, there is a similar distinction between the non-syllabic version of the vowel Template:IPA and a rare consonantal Template:IPA.<ref name="Trager" /><ref>Generally Template:IPA is Template:IPA though it may also be Template:IPA (Template:Harvcoltxt citing Template:Harvcoltxt and Template:Harvcoltxt).</ref> Near-minimal pairs include deshuesar Template:Audio-IPA ('to debone') vs. desuello Template:Audio-IPA ('skinning'), son huevos Template:Audio-IPA ('they are eggs') vs. son nuevos Template:Audio-IPA ('they are new'),<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> and huaca Template:Audio-IPA ('Indian grave') vs. u oca Template:Audio-IPA ('or goose').<ref name="Bowen 1955 236"/>

Vowels

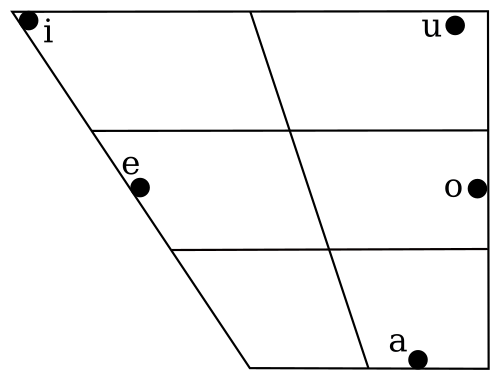

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | Template:IPA link | Template:IPA link | |

| Mid | Template:IPA link | Template:IPA link | |

| Open | Template:IPA link |

Spanish has five vowel phonemes, Template:IPA, Template:IPA, Template:IPA, Template:IPA and Template:IPA (the same as Asturian-Leonese, Aragonese, and also Basque). Each of the five vowels occurs in both stressed and unstressed syllables:<ref name="carrera256">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

| stressed | unstressed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word | gloss | word | gloss | ||

| piso | Template:Audio-IPA | 'I step' | pisó | Template:Audio-IPA | 'they (sg.) stepped' |

| pujo | Template:Audio-IPA | 'I bid' (present tense) | pujó | Template:Audio-IPA | 'they (sg.) bid' |

| peso | Template:Audio-IPA | 'I weigh' | pesó | Template:Audio-IPA | 'they (sg.) weighed' |

| poso | Template:Audio-IPA | 'I pose' | posó | Template:Audio-IPA | 'they (sg.) posed' |

| paso | Template:Audio-IPA | 'I pass' | pasó | Template:Audio-IPA | 'they (sg.) passed' |

Nevertheless, there are some distributional gaps or rarities. For instance, the close vowels Template:IPA are rare in unstressed word-final syllables.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt. Examples include words of Greek origin like énfasis Template:IPA ('emphasis'); the clitics su Template:IPA, tu Template:IPA, mi Template:IPA; the three Latin words espíritu Template:IPA ('spirit'), tribu Template:IPA ('tribe'), and ímpetu Template:IPA ('impetus'); and affective words like mami Template:IPA and papi Template:IPA.</ref>

There is no surface phonemic distinction between close-mid and open-mid vowels, unlike in Catalan, Galician, French, Italian and Portuguese. In the historical development of Spanish, former open-mid vowels Template:IPA were replaced with diphthongs Template:IPA in stressed syllables, and merged with the close-mid Template:IPA in unstressed syllables (Note, in word-initial position, Template:IPA occurs instead of Template:IPA).Template:Sfn The diphthongs Template:IPA regularly correspond to open Template:IPA in Portuguese cognates; compare siete Template:IPA 'seven' and fuerte Template:IPA 'strong' with the Portuguese cognates sete Template:IPA and forte Template:IPA, meaning the same.Template:Sfnp

There are some synchronic alternations between the diphthongs Template:IPA in stressed syllables and the monophthongs Template:IPA in unstressed syllables: compare heló Template:IPA 'it froze' and tostó Template:IPA 'he toasted' with hiela Template:IPA 'it freezes' and tuesto Template:IPA 'I toast'.Template:Sfnp It has thus been argued that the historically open-mid vowels remain underlyingly, giving Spanish seven vowel phonemes.Template:Sfnp

Because of substratal Quechua, at least some speakers from southern Colombia down through Peru can be analyzed to have only three vowel phonemes Template:IPA, as the close Template:IPA are continually confused with the mid Template:IPA, resulting in pronunciations such as Template:IPA for dulzura ('sweetness').Template:Clarify When Quechua-dominant bilinguals have Template:IPA in their phonemic inventory, they realize them as Template:IPA, which are heard by outsiders as variants of Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Both of those features are viewed as strongly non-standard by other speakers.

Allophones

Vowels are phonetically nasalized between nasal consonants or before a syllable-final nasal, e.g. Template:Lang Template:IPA ('five') and Template:Lang Template:IPA ('hand').<ref name="carrera256"/>

Arguably, Eastern Andalusian and Murcian Spanish have ten phonemic vowels, with each of the above vowels paired by a lowered or fronted and lengthened version, e.g. Template:Lang Template:IPA ('the mother') vs. Template:Lang Template:IPA ('the mothers').<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt. The first Template:IPA in Template:Lang also undergoes this fronting process as part of a vowel harmony system. See #Realization of /s/ below.</ref> However, these are more commonly analyzed as allophones triggered by an underlying Template:IPA that is subsequently deleted.

Exact number of allophones

There is no agreement among scholars on how many vowel allophones Spanish has; an often<ref>See e.g. Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> postulated number is five Template:IPA.

Some scholars,<ref>Such as Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> however, state that Spanish has eleven allophones: the close and mid vowels have close Template:IPA and open Template:IPA allophones, whereas Template:IPA appears in front Template:IPAblink, central Template:IPAblink and back Template:IPAblink variants. These symbols appear only in the narrowest variant of phonetic transcription; in broader variants, only the symbols Template:Angbr IPA are used,<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> and that is the convention adopted in the rest of this article.

Tomás Navarro Tomás describes the distribution of said eleven allophones as follows:<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt, cited on Joaquim Llisterri's site</ref>

- Close vowels Template:IPA

- The close allophones Template:IPA appear in open syllables, e.g. in the words Template:Lang Template:IPA 'free' and Template:Lang Template:IPA 'to raise'

- The open allophones are phonetically near-close Template:IPA, and appear:

- In closed syllables, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'end'

- In both open and closed syllables when in contact with Template:IPA, e.g. in the words Template:Lang Template:IPA 'rich' and Template:Lang Template:IPA 'blond'

- In both open and closed syllables when before Template:IPA, e.g. in the words Template:Lang Template:IPA 'son' and Template:Lang Template:IPA 'they (sg.) bid'

- Mid front vowel Template:IPA

- The close allophone is phonetically close-mid Template:IPAblink, and appears:

- In open syllables, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'finger'

- In closed syllables when before Template:IPA, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'Valencia'

- The open allophone is phonetically open-mid Template:IPAblink, and appears:

- In open syllables when in contact with Template:IPA, e.g. in the words Template:Lang Template:IPA 'war' and Template:Lang Template:IPA 'challenge'

- In closed syllables when not followed by Template:IPA, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'Belgian'

- In the diphthong Template:IPA, e.g. in the words Template:Lang Template:IPA 'comb' and Template:Lang Template:IPA king

- The close allophone is phonetically close-mid Template:IPAblink, and appears:

- Mid back vowel Template:IPA

- The close allophone is phonetically close-mid Template:IPAblink, and appears in open syllables, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'how'

- The open allophone is phonetically open-mid Template:IPAblink, and appears:

- In closed syllables, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'with'

- In both open and closed syllables when in contact with Template:IPA, e.g. in the words Template:Lang Template:IPA 'I run', Template:Lang Template:IPA 'mud', and Template:Lang Template:IPA 'oak'

- In both open and closed syllables when before Template:IPA, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'eye'

- In the diphthong Template:IPA, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'today'

- In stressed position when preceded by Template:IPA and followed by either Template:IPA or Template:IPA, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'now'

- Open vowel Template:IPA

- The front allophone Template:IPAblink appears:

- Before palatal consonants, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'office'

- In the diphthong Template:IPA, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'air'

- The back allophone Template:IPAblink appears:

- In the diphthong Template:IPA, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'flute'

- Before Template:IPA

- In closed syllables before Template:IPA, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'salt'

- In both open and closed syllables when before Template:IPA, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA 'chop'

- The central allophone Template:IPAblink appears in all other cases, e.g. in the word Template:Lang Template:IPA

- The front allophone Template:IPAblink appears:

According to Eugenio Martínez Celdrán, however, systematic classification of Spanish allophones is impossible since their occurrence varies from speaker to speaker and from region to region. According to him, the exact degree of openness of Spanish vowels depends not so much on the phonetic environment but rather on various external factors accompanying speech.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Diphthongs and triphthongs

| IPA | Example | Meaning | IPA | Example | Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Falling | Rising | |||||

| a | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | air | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | towards |

| Template:IPA | Template:Lang | pause | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | picture | |

| e | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | king | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | earth |

| Template:IPA | Template:Lang | neutral | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | fire | |

| o | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | today | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | radio |

| Template:IPA<ref>Template:IPA occurs rarely in words; another example is the proper name Template:Lang (Template:Harvnb). It is, however, common across word boundaries as with Template:Lang ('I have a house').</ref> | Template:Lang | seine fishing | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | quota | |

| Falling | Rising | |||||

| i | colspan="3" Template:N/a | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | we went | ||

| u | Template:IPA<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt points to Template:Lang ('very') as the one example with Template:IPA rather than Template:IPA. There are also a handful of proper nouns with Template:IPA, exclusive to Template:Lang (a nickname) and Template:Lang. There are no minimal pairs.</ref> | Template:Lang | very | Template:IPA | Template:Lang | widow |

Spanish has six falling diphthongs and eight rising diphthongs. While many diphthongs are historically the result of a recategorization of vowel sequences (hiatus) as diphthongs, there is still lexical contrast between diphthongs and hiatus.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Some lexical items vary by speaker or dialect between hiatus and diphthong. Words like Template:Lang ('biologist') with a potential diphthong in the first syllable and words like Template:Lang with a stressed or pretonic sequence of Template:IPA and a vowel vary between a diphthong and hiatus.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Template:Harvcoltxt hypothesize that this is caused by vocalic sequences being longer in those positions.

In addition to synalepha across word boundaries, sequences of vowels in hiatus become diphthongs in fast speech. When this happens, one vowel becomes non-syllabic (unless they are the same vowel in which case they fuse together) as in Template:Lang Template:IPA ('poet') and Template:Lang Template:IPA ('teacher').<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Similarly, the relatively rare diphthong Template:IPA may be reduced to Template:IPA in certain unstressed contexts, as in Template:Lang, Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In the case of verbs like Template:Lang ('relieve'), diphthongs result from the suffixation of normal verbal morphology onto a stem-final Template:IPA (that is, Template:Lang would be |Template:IPA| + |Template:IPA|).<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt.</ref> This contrasts with verbs like Template:Lang ('to extend') which, by their verbal morphology, seem to have stems ending in Template:IPA.<ref>See Template:Harvcoltxt for a more extensive list of verb stems ending in both high vowels, as well as their corresponding semivowels.</ref>

Non-syllabic Template:IPA and Template:IPA can be reduced to Template:IPA, Template:IPA, as in Template:Lang Template:IPA ('beatitude') and Template:Lang Template:IPA ('poetess'), respectively; similarly, non-syllabic Template:IPA can be completely elided, as in (Template:Lang Template:IPA 'right away'). The frequency (though not the presence) of this phenomenon varies by dialect: in a number it rarely occurs, while others always exhibit it.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Spanish also possesses triphthongs like Template:IPA and, in dialects that use a second-person plural conjugation, Template:IPA, Template:IPA, and Template:IPA (e.g. Template:Lang, 'ox'; Template:Lang, 'you change'; Template:Lang, '(that) you may change'; and Template:Lang, 'you ascertain').<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Prosody

Spanish is usually considered a syllable-timed language. Even so, stressed syllables may be up to 50% longer in duration than non-stressed syllables.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Although pitch, duration, and loudness contribute to the perception of stress,<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> pitch is the most important in isolation.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt, citing Template:Harvcoltxt, Template:Harvcoltxt, and the Esbozo de una nueva gramática de la lengua española. (1973) by the Gramática de la Real Academia Española.</ref>

Primary stress falls on the penultima (second-last syllable) 80% of the time. The other 20% of the time, stress falls on the ultima (last syllable) or on the antepenultima (third-last syllable).<ref name="Lleó">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> There are numerous minimal pairs that contrast solely in stress, such as Template:IPA Template:Lang ('sheet') and Template:IPA Template:Lang ('savannah'), as well as Template:IPA Template:Lang ('boundary'), Template:IPA Template:Lang ('[that] they (sg.) limit') and Template:IPA Template:Lang ('I limited').

Nonverbs are generally stressed on the penultimate syllable if they end in a vowel, and on the final syllable if they end in a consonant. Exceptions are marked orthographically (see below), and regular words are underlyingly phonologically marked with a stress feature [+stress].<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> There are exceptions to these tendencies, particularly learned words from Greek and Latin that feature antepenultimate stress.

In writing, stress is marked in certain circumstances with an acute accent (Template:Lang, Template:Lang, etc.). This is done according to the mandatory stress rules of Spanish orthography, which parallel the tendencies above (differing with words like Template:Lang) and are defined so as to unequivocally indicate where the stress lies in a given written word. An acute accent may also be used to differentiate homophones, such as Template:Lang ('my') and Template:Lang ('me'). In such cases, the accent is used on the homophone that normally receives greater stress when it is used in a sentence.

Lexical stress patterns are different between words carrying verbal and nominal inflection: in addition to the occurrence of verbal affixes with stress (something absent in nominal inflection), underlying stress also differs in that it falls on the last syllable of the inflectional stem in verbal words, while the stem of nominal words may have ultimate or penultimate stress.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In addition, in sequences of clitics suffixed to a verb, the rightmost clitic may receive secondary stress: Template:Lang Template:IPA ('look for it').<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt, citing Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Phonotactics

Template:More citations needed section

Syllable structure

Spanish syllable structure consists of an optional syllable onset, consisting of one or two consonants; an obligatory syllable nucleus, consisting of a vowel optionally preceded by and/or followed by a semivowel; and an optional syllable coda, consisting of one or two consonants.<ref name="Lipski 2016 p245">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> This can be summarized as follows (parentheses enclose optional components):

- (C1 (C2)) (S1) V (S2) (C3 (C4))

The following restrictions apply:

- Onset

- First consonant (C1): Can be any consonant.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt, Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Either Template:IPA or Template:IPA is possible as a word-internal onset after a vowel, but as discussed above, the contrast between the two rhotic consonants is neutralized at the start of a word or when the preceding syllable ends in a consonant: only Template:IPA is possible in those positions.

- Second consonant (C2): Can be Template:IPA or Template:IPA. Permitted only if the first consonant is a stop Template:IPA, a voiceless labiodental fricative Template:IPA, or marginally the nonstandard /v/.<ref>Vladimir | 357 pronunciations of Vladimir in Spanish (youglish.com)

Kevlar | 20 pronunciations of Kevlar in Spanish (youglish.com)

Chevrón | 43 pronunciations of Chevrón in Spanish (youglish.com)

Chevrolet | 84 pronunciations of Chevrolet in Spanish (youglish.com)</ref>Template:Citation needed Template:IPA is prohibited as an onset cluster in most of Peninsular Spanish, while Template:IPA sequences such as in Template:Lang 'athlete' are usually treated as an onset cluster in Latin America and the Canaries.<ref name="Lipski 2016 p245"/><ref name="HualdeTl">Template:Cite journal</ref><ref name="RAEtl">Template:Cite web</ref> The sequence Template:IPA is also avoided as an onset,<ref name="Lipski 2016 p245"/> seemingly to a greater degree than Template:IPA.<ref name="Morales-Front 2018 page=196">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

- Nucleus

- Semivowel (S1): Can be Template:IPA or Template:IPA, normally analyzed phonemically as allophones of non-syllabic Template:IPA. Cannot be identical to the following vowel (*Template:IPA and *Template:IPA do not occur within a syllable).

- Vowel (V): Can be any of Template:IPA.

- Semivowel (S2): Can be Template:IPA or Template:IPA, normally analyzed phonemically as allophones of non-syllabic Template:IPA. The sequences *Template:IPA, *Template:IPA and *Template:IPA do not occur within a syllable. Some linguists consider postvocalic glides to be part of the coda rather than the nucleus.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

- Coda

- First consonant (C3): Can be any consonant except Template:IPA, Template:IPA or Template:IPA.<ref name="Lipski 2016 p245"/>

- Second consonant (C4): Always Template:IPA in native Spanish words.<ref name="Lipski 2016 p245"/> Other consonants, except Template:IPA, Template:IPA and Template:IPA, are tolerated as long as they are less sonorous than the first consonant in the coda, such as in Template:Lang or the Catalan last name Template:Lang, but the final element is sometimes deleted in colloquial speech.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> A coda of two consonants never appears in words inherited from Vulgar Latin.

- In many dialects, a coda cannot be more than one consonant (one of n, r, l or s) in informal speech. Realizations like Template:IPA, Template:IPA, Template:IPA are very common, and in many cases, they are allowed even in formal speech.

Maximal onsets include Template:Lang Template:IPA, Template:Lang Template:IPA, Template:Lang Template:IPA.

Maximal nuclei include Template:Lang Template:IPA, Template:Lang Template:IPA.

Maximal codas include Template:Lang Template:IPA, Template:Lang Template:IPA.

Spanish syllable structure is phrasal, resulting in syllables consisting of phonemes from neighboring words in combination, sometimes even resulting in elision. The phenomenon is known in Spanish as Template:Lang.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> For a brief discussion contrasting Spanish and English syllable structure, see Template:Harvcoltxt.

Other phonotactic tendencies

- The palatal sonorants Template:IPA are rare in certain positions, although this may be a consequence of their diachronic origins (being derived often, though not exclusively, from Latin geminate consonants) rather than a matter of synchronic constraints.

- Per Baker 2004, the palatal sonorants Template:IPA are not found as word-internal onsets when the preceding syllable ends in a coda consonant or glide.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>{{ safesubst:#invoke:Unsubst||date=__DATE__ |$B=

Template:Fix }} A number of exceptions to this generalization exist, however, including prefixed or compound words (such as Template:Lang, Template:Lang, Template:Lang), borrowed words (such as Template:Lang,<ref>Listado de lemas que contienen «aiñ» | Diccionario de la lengua española | RAE - ASALE</ref> Template:Lang,<ref>Listado de lemas que contienen «aill» | Diccionario de la lengua española | RAE - ASALE</ref> Template:Lang,<ref>Listado de lemas que contienen «cll» | Diccionario de la lengua española | RAE - ASALE</ref> from Quechua), and forms that originate from non-Castilian Romance varieties (such as Asturian Template:Lang<ref>Listado de lemas que contienen «sll» | Diccionario de la lengua española | RAE - ASALE</ref>). The sequence Template:IPA occurs in some proper names, such as the toponym Auñón (from Latin Template:Lang<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>) and Auñamendi (a publishing house name taken from the Basque name of the Pic d'Anie); Template:IPA occurs in some words, such as Template:Lang and Template:Lang.<ref> Listado de lemas que contienen «aull» | Diccionario de la lengua española | RAE - ASALE</ref>

- Although word-initial Template:IPA is not forbidden (for example, it occurs in borrowed words such as Template:Lang and Template:Lang and in dialectal forms such as Template:Lang) it is relatively rare<ref name="Hualde 2022 page=793"/> and so may be described as having restricted distribution in this position.<ref name="Morales-Front 2018 page=196"/>

- In native Spanish words, the trill Template:IPA does not appear after a glide.<ref name="HualdeQuasiPhonemic"/> That said, it does appear after Template:IPA in some Basque loans, such as Aurrerá, a grocery store, Abaurrea Alta and Abaurrea Baja, towns in Navarre, Template:Lang, a type of dance, and Template:Lang, an adjective referring to poorly tilled land.<ref name="HualdeQuasiPhonemic"/>

- When the final syllable of a word begins with any of Template:IPA, the word typically does not display antepenultimate stress.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Epenthesis

Because of the phonotactic constraints, an epenthetic Template:IPA is inserted before word-initial clusters beginning with Template:IPA (e.g. Template:Lang 'to write') but not word-internally (Template:Lang 'to transcribe'),<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> thereby moving the initial Template:IPA to a separate syllable. Except in careful pronunciation, the epenthetic Template:IPA is pronounced even when it is not reflected in spelling (e.g. the surname of Carlos Slim is pronounced Template:IPA).<ref>Template:Cite web</ref> While Spanish words undergo word-initial epenthesis, cognates in Latin and Italian do not:

- Lat. status Template:IPA ('state') ~ It. stato Template:IPA ~ Sp. Template:Lang Template:IPA

- Lat. splendidus Template:IPA ('splendid') ~ It. splendido Template:IPA ~ Sp. Template:Lang Template:IPA

- Fr. slave Template:IPA ('Slav') ~ It. slavo Template:IPA ~ Sp. Template:Lang Template:IPA

In addition, Spanish adopts foreign words starting with pre-nasalized consonants with an epenthetic Template:IPA. Template:Lang, a prominent last name from Equatorial Guinea, is pronounced as Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

When adapting word-final complex codas that show rising sonority, an epenthetic Template:IPA is inserted between the two consonants. For example, Template:Lang is typically pronounced Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Occasionally Spanish speakers are faced with onset clusters containing elements of equal or near-equal sonority, such as Template:Lang (a German last name that is common in parts of South America). Assimilated borrowings usually delete the first element in such clusters, as in Template:Lang 'psychology'. When attempting to pronounce such words for the first time without deleting the first consonant, Spanish speakers insert a short, often devoiced, schwa-like vowel between the two consonants.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Alternations

Some alternations exist in Spanish that reflect diachronic changes in the language and arguably reflect morphophonological processes rather than strictly phonological ones. For instance, some words alternate between Template:IPA and Template:IPA or Template:IPA and Template:IPA, with the latter in each pair appearing before a front vowel:<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

| word | gloss | word | gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| opaco | Template:IPA | 'opaque' | opacidad | Template:IPA | 'opacity' |

| sueco | Template:IPA | 'Swedish' | Suecia | Template:IPA | 'Sweden' |

| belga | Template:IPA | 'Belgian' | Bélgica | Template:IPA | 'Belgium' |

| análogo | Template:IPA | 'analogous' | analogía | Template:IPA | 'analogy' |

Note that the conjugation of most verbs with a stem ending in Template:IPA or Template:IPA does not show this alternation; these segments do not turn into Template:IPA or Template:IPA before a front vowel:

| word | gloss | word | gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seco | Template:IPA | 'I dry' | seque | Template:IPA | '(that) I/they (sg.) dry (subjunctive)' |

| castigo | Template:IPA | 'I punish' | castigue | Template:IPA | '(that) I/they (sg.) punish (subjunctive)' |

There are also alternations between unstressed Template:IPA and Template:IPA and stressed Template:IPA (or Template:IPA, when initial) and Template:IPA respectively:<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

| word | gloss | word | gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| heló | Template:IPA | 'it froze' | hiela | Template:IPA | 'it freezes' |

| tostó | Template:IPA | 'he toasted' | tuesto | Template:IPA | 'I toast' |

Likewise, in a very small number of words, alternations occur between the palatal sonorants Template:IPA and their corresponding alveolar sonorants Template:IPA (Template:Lang/Template:Lang 'maiden'/'youth', Template:Lang/Template:Lang 'to scorn'/'scorn'). This alternation does not appear in verbal or nominal inflection (that is, the plural of Template:Lang is Template:Lang, not Template:Lang).<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> This is the result of geminated Template:IPA and Template:IPA of Vulgar Latin (the origin of Template:IPA and Template:IPA, respectively) degeminating and then depalatalizing in coda position.<ref name="Pensado">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Words without any palatal-alveolar allomorphy are the result of historical borrowings.<ref name="Pensado" />

Other alternations include Template:IPA ~ Template:IPA (Template:Lang vs. Template:Lang),<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Template:IPA ~ Template:IPA (Template:Lang vs. Template:Lang).<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Here the forms with Template:IPA and Template:IPA are historical borrowings and the forms with Template:IPA and Template:IPA forms are inherited from Vulgar Latin.

There are also pairs that show antepenultimate stress in nouns and adjectives but penultimate stress in synonymous verbs (Template:Lang 'vomit' vs. Template:Lang 'I vomit').<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Acquisition as first language

Phonology

Phonological development varies greatly by individual for both those developing regularly and those with delays. However, a general pattern of acquisition of phonemes can be inferred by the level of complexity of their features, i.e. by sound classes.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> A hierarchy may be constructed, and if a child is capable of producing discrimination on one level, they will also be capable of making the discriminations of all prior levels.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

- The first level consists of stops (without a voicing distinction), nasals, Template:IPA, and optionally a non-lateral approximant. This includes a labial/coronal place difference (Template:IPA vs. Template:IPA and Template:IPA vs. Template:IPA).

- The second level includes voicing distinction for oral stops and a coronal/dorsal place difference. This allows for a distinction between Template:IPA, Template:IPA, and Template:IPA, along with their voiced counterparts, as well as a distinction between Template:IPA and the approximant Template:IPA.

- The third level includes fricatives and/or affricates.

- The fourth level introduces liquids other than Template:IPA, Template:IPA and Template:IPA. It also introduces Template:IPA.

- The fifth level introduces the trill Template:IPA.

This hierarchy is based on production only and is a representation of a child's capacity to produce a sound, whether that sound is the correct target in adult speech or not. Thus, it may contain some sounds that are not included in adult phonology but are produced as a result of error.

Spanish-speaking children will accurately produce most segments at a relatively early age. By around three-and-a-half years, they will no longer productively use phonological processesTemplate:Clarify the majority of the time. Some common error patterns (found 10% or more of the time) are cluster reduction, liquid simplification, and stopping. Less common patterns (evidenced less than 10% of the time) include palatal fronting, assimilation, and final consonant deletion.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Typical phonological analyses of Spanish consider the consonants Template:IPA, Template:IPA, and Template:IPA the underlying phonemes and their corresponding approximants Template:IPA, Template:IPA, and Template:IPA allophonic and derivable by phonological rules. However, approximants may be the more basic form because monolingual Spanish-learning children learn to produce the continuant contrast between Template:IPA and Template:IPA before they produce the lead voicing contrast between Template:IPA and Template:IPA.<ref name="Macken80b">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> (In comparison, English-learning children are able to produce adult-like voicing contrasts for these stops well before age three.)<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> The allophonic distribution of Template:IPA and Template:IPA produced in adult speech is not learned until after age two and not fully mastered even at age four.<ref name="Macken80b"/>

The alveolar trill Template:IPA is one of the most difficult sounds to produce in Spanish and is acquired later in development.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Research suggests that the alveolar trill is acquired and developed between the ages of three and six years.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Some children acquire an adult-like trill within this period, and some fail to properly acquire the trill. The attempted trill sound of the poor trillers is often perceived as a series of taps owing to hyperactive tongue movement during production.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> The trill is also often very difficult for those learning Spanish as a second language, sometimes taking over a year to be produced properly.<ref>Template:Cite web</ref>

Codas

One study found that children acquire medial codas before final codas, and stressed codas before unstressed codas.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Since medial codas are often stressed and must undergo place assimilation, greater importance is accorded to their acquisition.<ref name="Lleó278">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Liquid and nasal codas occur word-medially and at the ends of frequently-used function words and so they are often acquired first.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Prosody

Research suggests that children overgeneralize stress rules when they are reproducing novel Spanish words and that they have a tendency to stress the penultimate syllables of antepenultimately stressed words to avoid a violation of nonverb stress rules that they have acquired.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Many of the most frequent words heard by children have irregular stress patterns or are verbs, which violate nonverb stress rules.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> This complicates stress rules until ages three to four, when stress acquisition is essentially complete, and children begin to apply these rules to novel irregular situations.

Dialectal variation

Some features, such as the pronunciation of voiceless stops Template:IPA, have no dialectal variation.<ref name="cotton55">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> However, there are numerous other features of pronunciation that differ from dialect to dialect.

Yeísmo

Template:Main One notable dialectal feature is the merging of the voiced palatal approximant Template:IPAblink (as in ayer) with the palatal lateral approximant Template:IPAblink (as in Template:Lang) into one phoneme (yeísmo), with Template:IPA losing its laterality. While the distinction between these two sounds has traditionally been a feature of Castilian Spanish, this merger has spread throughout most of Spain in recent generations, particularly outside of regions in close linguistic contact with Catalan and Basque.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In Spanish America, most dialects are characterized by this merger, with the distinction persisting mostly in parts of Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, and northwestern Argentina.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In the other parts of Argentina, the phoneme resulting from the merger is realized as Template:IPAblink,<ref name="carrera258"/> and in Buenos Aires. the sound has recently been devoiced to Template:IPAblink for the younger population, a change that is spreading throughout Argentina.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Seseo, ceceo and distinción

Speakers in northern and central Spain, including the variety prevalent on radio and television, have both Template:IPA and Template:IPA (distinción, 'distinction'). However, speakers in Latin America, the Canary Islands and some parts of southern Spain have only Template:IPA (seseo), which in southernmost Spain is pronounced Template:IPA, not Template:IPA (ceceo).<ref name="carrera258"/>

Realization of Template:IPA

Template:Also The phoneme Template:IPA has three different pronunciations depending on the dialect area:<ref name="carrera258"/><ref name="Dalbor 1980"/><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

- An Template:Lcons alveolar retracted fricative (or "apico-alveolar" fricative) Template:IPA, which sounds similar to English Template:IPA and is characteristic of the northern and central parts of Spain and is also used by many speakers in Colombia's Antioquia Department.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref><ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

- A Template:Lcons alveolar grooved fricative Template:IPA, much like the most common pronunciation of English Template:IPA, is characteristic of western Andalusia (e.g. Málaga, Seville, and Cádiz), the Canary Islands, and Latin America.

- An Template:Lcons dental grooved fricative Template:IPA (ad hoc symbol), which has a lisping quality and sounds something like a cross between English Template:IPA and Template:IPA but is different from the Template:IPA occurring in dialects that distinguish Template:IPA and Template:IPA. It occurs only in dialects with ceceo, mostly in Granada, in parts of Jaén, in the southern part of Sevilla and the mountainous areas shared between Cádiz and Málaga.

Obaid describes the apico-alveolar sound as follows:<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt.</ref> Template:Blockquote

Dalbor describes the apico-dental sound as follows:<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt.</ref> Template:Blockquote

In some dialects, Template:IPA may become the approximant Template:IPA in the syllable coda (e.g. doscientos Template:IPA 'two hundred').<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt citing Template:Harvcoltxt and Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In southern dialects in Spain, most lowland dialects in the Americas, and in the Canary Islands, it debuccalizes to Template:IPA in final position (e.g. niños Template:IPA 'children'), or before another consonant (e.g. Template:Lang Template:IPA 'match') and so the change occurs in the coda position in a syllable. In Spain, this was originally a southern feature, but is now expanding rapidly to the north.<ref name="Penny2000p122"/>

From an autosegmental point of view, the Template:IPA phoneme in Madrid is defined only by its voiceless and fricative features. Thus, the point of articulation is not defined and is determined from the sounds after it in a word or sentence. In Madrid, the following realizations are found: Template:IPA > Template:IPA<ref>Template:Cite thesis</ref> and Template:IPA > Template:IPA. In parts of southern Spain, the only feature defined for Template:IPA appears to be voiceless; it may lose its oral articulation entirely to become Template:IPA or even a geminate with the following consonant (Template:IPA or Template:IPA from Template:IPA 'same').<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In Eastern Andalusian and Murcian Spanish, word-final Template:IPA, Template:IPA and Template:IPA regularly weaken, and the preceding vowel is lowered and lengthened:<ref name="Vicente">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

- Template:IPA > Template:IPAblink e.g. mis Template:IPA ('my' pl)

- Template:IPA > Template:IPAblink e.g. mes Template:IPA ('month')

- Template:IPA > Template:IPAblink e.g. más Template:IPA ('plus')

- Template:IPA > Template:IPAblink e.g. tos Template:IPA ('cough')

- Template:IPA > Template:IPAblink e.g. tus Template:IPA ('your' pl)

A subsequent process of vowel harmony takes place and so Template:Lang ('far') is Template:IPA, Template:Lang ('you [plural] have') is Template:IPA and Template:Lang ('clovers') is Template:IPA or Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

Coda simplification

Southern European Spanish (Andalusian Spanish, Murcian Spanish, etc.) and several lowland dialects in Latin America (such as those from the Caribbean, Panama, and the Atlantic coast of Colombia) exhibit more extreme forms of simplification of coda consonants:

- word-final dropping of Template:IPA (e.g. compás Template:IPA 'musical beat' or 'compass')

- word-final dropping of nasals with nasalization of the preceding vowel (e.g. ven Template:IPA 'come')

- dropping of Template:IPA in the infinitival morpheme (e.g. comer Template:IPA 'to eat')

- the occasional dropping of coda consonants word-internally (e.g. doctor Template:IPA 'doctor').<ref name="Guitart">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

The dropped consonants appear when additional suffixation occurs (e.g. compases Template:IPA 'beats', venían Template:IPA 'they were coming', comeremos Template:IPA 'we will eat'). Similarly, a number of coda assimilations occur:

- Template:IPA and Template:IPA may neutralize to Template:IPA (e.g. Cibaeño Dominican celda/cerda Template:IPA 'cell'/'bristle'), to Template:IPA (e.g. Caribbean Spanish alma/arma Template:IPA 'soul'/'weapon', Andalusian Spanish sartén Template:IPA 'pan'), to Template:IPA (e.g. Andalusian Spanish alma/arma Template:IPA) or, by complete regressive assimilation, to a copy of the following consonant (e.g. pulga/purga Template:IPA 'flea'/'purge', carne Template:IPA 'meat').<ref name="Guitart" />

- Template:IPA, Template:IPA, (and Template:IPA in southern Peninsular Spanish) and Template:IPA may be debuccalized or elided in the coda (e.g. los amigos Template:IPA 'the friends').<ref name="Guitart1">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

- Stops and nasals may be realized as velar (e.g. Cuban and Venezuelan étnico Template:IPA 'ethnic', himno Template:IPA 'anthem').<ref name="Guitart1" />

Final Template:IPA dropping (e.g. mitad Template:IPA 'half') is general in most dialects of Spanish, even in formal speech.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

The neutralization of syllable-final Template:IPA, Template:IPA, and Template:IPA is widespread in most dialects (with e.g. Pepsi being pronounced Template:IPA). It does not face as much stigma as other neutralizations and may go unnoticed.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref>

The deletions and neutralizations show variability in their occurrence, even with the same speaker in the same utterance, so non-deleted forms exist in the underlying structure.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> The dialects may not be on the path to eliminating coda consonants since deletion processes have been existing for more than four centuries.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt, citing Template:Harvcoltxt and Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> Template:Harvcoltxt argues that it is the result of speakers acquiring multiple phonological systems with uneven control like that of second language learners.

In Standard European Spanish, the voiced obstruents Template:IPA before a pause are devoiced and laxed to Template:IPA (Template:IPA), as in club Template:IPA ('[social] club'), sed Template:IPA ('thirst'), zigzag Template:IPA.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt citing Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> However, word-final Template:IPA is rare, and Template:IPA is even more so. They are restricted mostly to loanwords and foreign names, such as the first name of the former Real Madrid sports director Predrag Mijatović, which is pronounced Template:IPA, and after another consonant, the voiced obstruent may even be deleted, as in iceberg, pronounced Template:IPA.<ref>The Oxford Spanish Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 1994).</ref> In Madrid and its environs, sed is alternatively pronounced Template:IPA, and the aforementioned alternative pronunciation of word-final Template:IPA as Template:IPA co-exists with the standard realization,<ref name="molina">Template:Cite journal</ref> but is otherwise nonstandard.<ref name=salgado/>

Loan sounds

The fricative Template:IPA may also appear in borrowings from other languages, such as Nahuatl<ref name="blanch29">Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> and English.<ref>Template:Harvcoltxt</ref> In addition, the affricates Template:IPAslink and Template:IPAslink also occur in Nahuatl borrowings.<ref name="blanch29"/> That said, the onset cluster Template:IPA is permitted in most of Latin America, the Canaries, and the northwest of Spain, and the fact that it is pronounced in the same amount of time as the other voiceless stop + lateral clusters Template:IPA and Template:IPA support an analysis of the Template:IPA sequence as a cluster, rather than an affricate, in Mexican Spanish.<ref name="HualdeTl" /><ref name="RAEtl" />

Sample

Template:Listen This sample is an adaptation of Aesop's "El Viento del Norte y el Sol" (The North Wind and the Sun) read by a man from Northern Mexico born in the late 1980s. As usual in Mexican Spanish, Template:IPA and Template:IPA are not present.

Orthographic version

Phonemic transcription

Phonetic transcription

See also

- History of the Spanish language

- List of phonetics topics

- Spanish dialects and varieties

- Stress in Spanish

- Template:Annotated link

References

Citations

Bibliography

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

Further reading

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation